Like a large, silent pipit disappearing into the sun despite frantically mumbled prayers, it's flown by. Hard to believe, but it really has been more than four years since my wife Amity and I returned from a year-long round-the-world birding and backpacking honeymoon and washed up on the hallowed shores of Filey Bay. And flown by it surely has, which makes it all the more timely to look back on what has been an always entertaining, often memorable and occasionally mind-blowing period of east coast patch birding.

Of the many scarcities and drift migrants attracted to the grassy plateau of Carr Naze, Wrynecks take a lot of beating.

I'd no great expectations heading out on my debut circuit back in spring 2012, but it's hard avoid the sense that the supremely tame Great Grey Shrike which magically materialised in front of me that morning wasn't some kind of harbinger, raising the curtain on a memorably lucky first spring that provided all the avian inspiration I could possibly need. Along with local, bird-related work falling into my lap, the die was cast within the first couple of months, allowing me to immerse myself in the kind of fantasy coastal patch I could only dream of back in the maelstrom of east London.

Filey, of course, has a fine reputation for quality birds and birding stretching back many decades (especially for those with longer memories), and for some years enjoyed a period of enviably blanket coverage; with competing rival cliques forensically fine tooth-combing what was then a significantly easier area to cover, some fantastic returns were inevitably produced. Fast forward to the spring of 2012, however, and Filey had long since slipped into a kind of slumber, its pulse increasingly faint on the national (and even county) radar. A mass exodus of quality birders, a lack of new blood, increasingly challenging habitat, increased disturbance and a steadily fading reputation all fed into the perception, internally and externally, that the good old days were long gone.

Whooper Swans are among the many species which use the Yorkshire coast as a flyway every autumn.

Of course, I've been told about the good old days (and how they'd never come back) more times than I can remember, and there are some mouth-watering stories to enjoy. And yet, even during this apparent heyday — with every inch of hedgerow scoured, every inch of space in the seawatch hide at a premium, and front-line coverage at a level that will perhaps never be seen again — Filey still failed to deliver a national rarity on an annual basis, sometimes with just a handful of county rares to show for countless observer hours over a given year. Nostalgia can be a foggy notion.

Personally, my only birding ambitions on arrival here lay in relishing and absorbing the full spectrum of migration in all its forms, ideally sprinkled with a handful of local rarities — the odd Red-breasted Flycatcher, Icterine Warbler, Long-tailed Skua and the like — to keep the engine ticking over; with luck, scoring a classy county rare or two would put the cherry on the cake. As for a national rarity, well, if hardcore collective efforts couldn't reliably muster one annually when coverage was at its most saturated, then I'd surely have to be very lucky.

A sunny day on a busy cliff-top path at the end of April wasn't how Mark anticipated finding an Olive-backed Pipit on his new patch, just a couple of weeks after arriving.

It's fair to say, then, that those tempered but realistic expectations have been joyously and systematically blown to pieces. Four years may not seem like a very long time in the grand scheme of things, but a personal haul including a first for Britain, a (live) first for England, annual national rarities, a handful of county rarities per year, dozens of local rares and numerous incredible birding experiences later, and you could say that my own personal perception of Filey's heyday is a little different.

Growing up over the bay on the Great White Cape of Flamborough Head meant seabirds were a bigger part of my childhood than TV, video games and school combined. Sharing a house with them, meanwhile, seemed perfectly normal at the time, after my old man turned our home into an ad-hoc bird hospital (“you can't have a bath, it's full of bloody Puffins again” being one of many memorable maternal quotes from around that time). Pinned helplessly against the old fog station fence in a gale force northerlies, meanwhile, was a rite of passage that was equally memorable, and not just for the pure fear; thousands of Little Auks bulleting by like tiny Orcas and unbroken lines of shearwaters snaking between high peaks and deep troughs are not easily forgotten, no matter how immersed in other temptations you latterly become.

Common migrants can be just as captivating as scarce ones, often more so — as with the Swallow families congregating at Carr Naze pond.

Back in the box-seat of Yorkshire coast seawatching after so long (this time by choice), those distant memories were soon overshadowed by glorious contemporary live action, and the Brigg hide fast became my favourite human-made structure on the planet. It's an immovable blessing that I count on every seawatch, particularly when it's really needed. As a rule of thumb, the best of the action — particularly as the autumn wears on — happens in the most adverse of conditions with the strongest, most dangerous winds, and those most memorable of sessions simply wouldn't be possible without the precious shelter it provides.

As any real (i.e. masochistic) sea-watcher knows, you can't fully savour your rewards without the requisite suffering, and here at Filey there's a ritual to perform before every special session. Assuming you've made it as far as the end of Carr Naze (the exposed plateau which crowns the Brigg itself) — no mean feat when confronted by those storm-force but ultimately prize-delivering winds — there's the small matter of negotiating the steep, slippery slope down to the hide. The fact that I'm yet to be the subject of a Coastguard rescue is perhaps more down to luck than judgement, but it's a calculated risk that pays out for those foolish enough to stumble and slide precariously down the precipice.

Top of the 'most-wanted' list, two arrived within the same 48 hours on Mark's regular circuit during mid-October easterlies.

And how it's paid out. It may be very much an acquired taste, but it's hard to think of a more addictive and (at times) exhilarating aspect of birding once you've fallen under its spell. The beauty of the sea (particularly in peak season) is, you never quite know what it's going to produce: there are those times when you roll the die and hope for the best, and there are those when you just know it's going to be a classic.

Those bolt-on classic Filey seawatching days — when you hardly need an alarm to propel you out of bed before dawn — almost always involve a dose of magical northerlies, usually (but not always) in autumn. They'll typically involve at least three shearwater species (ideally with the quintessentially east coast spectacle of Sootys streaming effortlessly by), skuas bombing past the hide in unruly mobs (ideally with Poms and/or Long-tails in the thick of the action), and are always peppered with a wide variety of other quality to keep the bar high: a few Red-necked Grebes perhaps, a Sabine's Gull battling north with Kittiwakes, a few Velvet Scoters or Scaup, a Leach's Storm-petrel materialising briefly between troughs, a Grey Phalarope dropping into the surf, or any number of other possibilities. Days like these — which, magically, happen every season, at least a handful of times — can be so hypnotic and enthralling that it's not unusual for eight hours to pass in what seems like one or two; and there are many others which, while not quite hitting the same heights, still make it almost as hard to pack up the 'scope after a few hours of North Sea magic.

A dramatic feature of late autumn sea-watches involves Short-eared Owls battling to make landfall against winds and waves.

While producing the goods with an affirming frequency, sea-watching as an aspect of patch birding is always going to be more about the spectacle and the movement than, say, the pursuit of rarities; consequently, an almost infinitely higher percentage of ones-that-got-away applies, and a suitably philosophical disposition is required to let them all go.

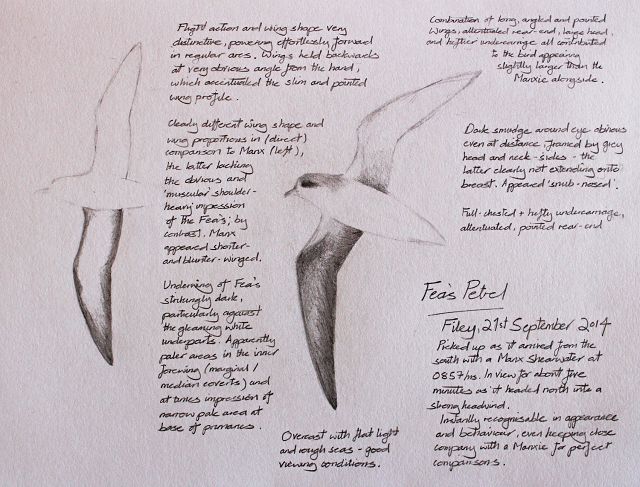

Well, most of them. There are times when it comes together beautifully, of course, and it was on one of those classic September days two years ago that — in among an almost unbroken parade of Sootys and skuas — a cracking Fea's-type Petrel arced gracefully into my field of view, spending a full five minutes skimming the white horses before being tracked steadily north as far as the Farnes. Priceless.

The holy grail for many sea-watchers — a Fea's Petrel graced Mark's notebook (and most of the east coast) in September 2014.

But, as mentioned, it's not always the killer seawatches that provide the killer birds. An early morning session a couple of months later promised little on paper (and with a birding trip to pack for later in the day, I nearly didn't bother), but a lone Tundra Bean Goose honking loudly as it cruised close by at eye-level as I descended the slope felt like a good omen. An hour or so later and with effectively nothing on the move except a trickle of Red-throated Divers, I thought about calling it a day, but a close Great Northern delayed my exit for a while; satisfyingly, a decision more than justified by a Black-throat following the same line a few minutes later. Three diver species in 35 minutes, then — a surprisingly quality haul on such an otherwise quiet morning overall. Again entertaining thoughts of quitting while I was ahead (spot the theme), a monster of a diver suddenly appeared in the 'scope from the north — thick-set, bull-necked, large-headed (with a squarish profile) and distinctly pot-bellied... surely not?

December has a habit of producing the goods for Mark, with White-billed Diver, Brünnich's Guillemot and this Surf Scoter in the last three ...

Following its laboured flight closer inshore, a big, heavy, pale, upturned bill came into focus, and switching to the camera, I promptly lost the bird, filled the (otherwise empty) hide with profanities and panicked, luckily picking it up again as it broke the horizon and gained height. Frantic calls to potential observers found only voicemails, but were soon followed by the good news from Brett that he'd watched it passing Flamborough 13 minutes later (at a speed of 32 mph, according to his calculations). Four diver species, including a show-stopping White-billed, in 45 minutes — the stuff my birding dreams were made of, emphatically realised on a quiet December morning just a few minutes from my front door.

Countless hours hunched within breeze-blocks on an exposed promontory is one way of getting your seabird kicks (and I'd recommend it to anyone), but if you want to find a truly heart-stopping, off-the-radar, once-in-a-lifetime Arctic wanderer, there's only one sure-fire method: a gentle evening stroll along the promenade with the Mrs. For the benefit of my birding friends at least I'll stop short of rolling out the story again (although it is here if required), but suffice to say, bumping into a Brünnich's Guillemot just beyond the end of your road on a quiet December afternoon isn't an experience you forget in a hurry.

Brünnich's Guillemot — a first for Yorkshire — swimming innocently by the evening strollers on the promenade ...

The real beauty of birding here is the variety and proximity of contrasting habitats. The bay itself — a glorious, sweeping, sheltered curve stretching from the Brigg to Bempton — is something I've waxed lyrically about at length on these pages before (see here), but it just can't be ignored, even in underwhelming conditions. A more recent example: scanning a seemingly birdless, discouragingly choppy surface on a murky, nondescript day in December last year (December yet again — it's the new October...) was almost completely forgettable until a distant dark blob with a seemingly angular head briefly bobbed into my view. Five and half months, hundreds of appreciative visitors and countless razorfish later, and a by-then much smarter young male Surf Scoter finally bid us so long. The bay strikes again, as it will doubtless continue to do.

But exploiting enviably quality sea-watching opportunities and an outrageously productive bay are only part of the coastal story here. In any other circumstances they'd be more than enough, but one of the most uniquely alluring (and uniquely Filey) birding experiences is provided by the rugged, picturesque environs of the Brigg itself. Its inherently transient nature means no days, or even hours, are ever the same — even at its mid-summer worst (when covered in anglers, tourists and dogs), the chances are you'll have it pretty much to yourself by the time the next tide wipes the slate clean, if not before, and the avian cast will have changed subtly or dramatically.

One of several Little Stints which have afforded unbeatably close-up views on the Brigg, this one roosting within two metres of the observer

I could drone on forever about the magic of the Brigg (having already done so on these pages before), but if there's a better place to enjoy beautiful Arctic waders at point-blank range — away from the Arctic, at least — I'm not aware of it. Point-blank, as in, almost at your toes — or better still, if you get closer to their level, at your knees and elbows. I've spent more hours than I can recall doing exactly that, and will never even vaguely tire of this simplest and most thrilling of birding experiences. And it's not just the Purple Sandpipers and other locally common shorebirds: in my first September I had a Little Stint wander up to me and promptly go to sleep within reaching distance, which at the time I assumed must be a very special one-off — a few years later, and it's an annual event I look forward to every autumn.

Not to be outdone, this White-rumped Sandpiper was just as tame a couple of weeks ago.

Rivalling and maybe even surpassing all the above for sheer birding thrills, however, is perhaps my favourite aspect of local birding — watching birds physically arriving in off the North Sea. Filey may not have the huge, imposing headland of Flamborough thrusting many miles out towards the continent, or the long, perfectly narrowing bottleneck of Spurn's legendary peninsula, but the superficially modest promontory of the Brigg is a formidable secret weapon. Projecting just a few of hundred metres out into the North Sea, the 'runway' it provides as first contact for migrants is magnetic; given the right conditions (murky with an easterly wind in autumn is perfect, but not always required), standing out on Carr Naze — the grassy plateau that crowns the Brigg itself — and letting migration unfold around you can be nothing short of electrifying.

Whether it’s the mass arrival of squadrons of Scandinavian thrushes, a sudden fall of Yellow-browed Warblers hopping around in the clifftop grass, a carpet of Goldcrests contact-calling like a hundred tiny wind chimes, a Wryneck dropping out of the sky and onto the path just a few steps away, clumsy parties of finches and buntings weighing down weakened umbellifers, or a scarcity suddenly materialising at close range out of the blue (I've had Olive-backed Pipit, Greenish Warbler and various others do so) — it's migration at its most pure, visceral and captivating.

Another target bird, Greenish Warbler is one of many scarce passerines to have appeared in front of Mark in the magic bush on the side of Carr Naze.

Away from the Brigg and Carr Naze, birding the land here may indeed be somewhat more challenging these days — most of those isolated, easily worked patches of scrub are dense, often impenetrable black holes now, and the exponential increase in dogs and their zombified charges would sorely test the resolve of a zen master — but there's a lot to be grateful for. Most of the land here is accessible, after all; better still, some of the key spots are ours (Filey Bird Observatory's), so they're pretty much disturbance-free and managed purely for birds and wildlife. And while a few quality front-line birders would be very welcome (bribes are available, so get in touch), as a place to quietly and determinedly find and enjoy your own rewards away from the birding masses, it's an absolute godsend.

There's no doubt that populations of many of the traditional east coast songbird migrants have decreased, and that those worrying downward trends are seemingly irreversible. It's not always so gloomy in the thick of migration season however, and in the last couple of years, for example, we've broken day count records for a host of species, including Redwing (10,500), Pied Flycatcher (64) and Yellow-browed Warbler (34 — a couple of days ago, and more three times the previous day record!), and that's without considering recent counts for seabirds and various other groups.

Filey Bird Observatory's East Lea reserve is a magnet for flava wagtails, with four subspecies dropping in over the last two springs (including this flavissima).

And then, if such things light your fire (as they do mine, for better or worse), there's the unique buzz that comes from finding exotic passerine waifs and strays among the more expected visitors. Beyond the odd stat-defying lucky strike, their pursuit naturally requires plenty of time, energy, patience and focus; but by playing to certain other strengths — in my case, a dogged, vaguely psychotic persistence — I've been lucky enough to come across many more than I could have anticipated over these last four years or so.

Of those highlights, there are happily plenty, and while I've been fortunate to stumble on much rarer birds here, clocking and then pinning down the indignant tacks of two skulking Dusky Warblers, 48 hours and 400 metres apart, is pretty much as good as it gets (at least, for someone with a long-held obsession to do so). Perhaps most gratifying of all so far, however, has to be the Spanish Wagtail that dropped onto East Lea, one of our wetland reserves, last April: when you're tapping away in a hide you've adopted as your temporary office, hear a distinctive call, look up and come face to face with a sublime first for Britain, you know you've come to the right place.

There are those birds which are on the radar, and then there are those which completely blindside you — the latter being very much the case with this male Spanish Wagtail last spring

There are various anomalies that, even if I stay for many more years, won't all be ironed out, but that's one of the beauties of patch birding. Truly rare shorebirds are at a premium here, for example, and aside from finding a White-rumped Sandpiper at the Dams not long after arriving (and enjoying the recent ridiculously tame bird a week or two back on — guess where — the Brigg), I've yet to get a clear shot at a more desirable peep or Calidrid. The skies, meanwhile, have been slightly underwhelming, despite much neck strain — aside from a good few Common Cranes, a handful of Honey-buzzards, a point-blank Rough-leg in off and the more expected migrants (including Ospreys and Red Kites), the big one has yet to glide into view. Likewise, gulls have been surprisingly uninspiring, despite much effort thus far. (Ross’s or Ivory for this year's traditional December deity, then, if you don't mind.)

Even without such anomalies, there are still many, many more empty boxes on the wish-list, an almost endless roll-call of potential targets to aim for, and a host of new and uniquely Filey experiences to savour over the coming seasons. It's the east coast, after all, and as birding playgrounds go, I'm supremely blessed. There's everything to play for, and what a place to do so.

Mark is co-running the Filey Ringing & Migration Week, 15-22 October 2016. All events are free; see www.fbog.co.uk for details.

Resources:

Mark's writing — http://markjamespearson.wordpress.com/

Mark's blog — Northern Rustic

Filey Brigg Ornithological Group