The Birder's Guide to Africa

In this new book, Michael Mills has gone for a different approach to the traditional where-to-watch guide, putting finding the birds before finding the country. This is achieved in three main sections: Country Accounts, Family Accounts and Species Accounts, taking respectively 108, 150 and 244 pages, so the clear emphasis is on the birds themselves.

In this new book, Michael Mills has gone for a different approach to the traditional where-to-watch guide, putting finding the birds before finding the country. This is achieved in three main sections: Country Accounts, Family Accounts and Species Accounts, taking respectively 108, 150 and 244 pages, so the clear emphasis is on the birds themselves.

In the introduction, readers are invited to decide whether they regard themselves as world listers, balanced birders, leisure birders, budget birders or explorers. There follow four maps of the African region, with the countries coloured in reds of varying intensity, the deeper the tint indicating the greater attractiveness for the relevant user. Thus on the world lister’s map, areas of high endemism are the criterion.

There are also tables assigning a rating from 1 to 10 for each territory based on such criteria as ease of travel, safety, bird diversity, endemism, cost and so on. The methods used in arriving at these scores are explained in some detail, and on the inside front cover is a map of Africa showing the total scores for each area. The geographical coverage is wide enough to include Madagascar, as well as many oceanic islands, the Azores and Sinai.

The country accounts offer basic data about habitats, birding, travel, climate and so on, varying in length according to the relative importance of the country. Ethiopia, for instance, merits about three pages, while most are one or two. There are no maps or details of good birding sites in each country.

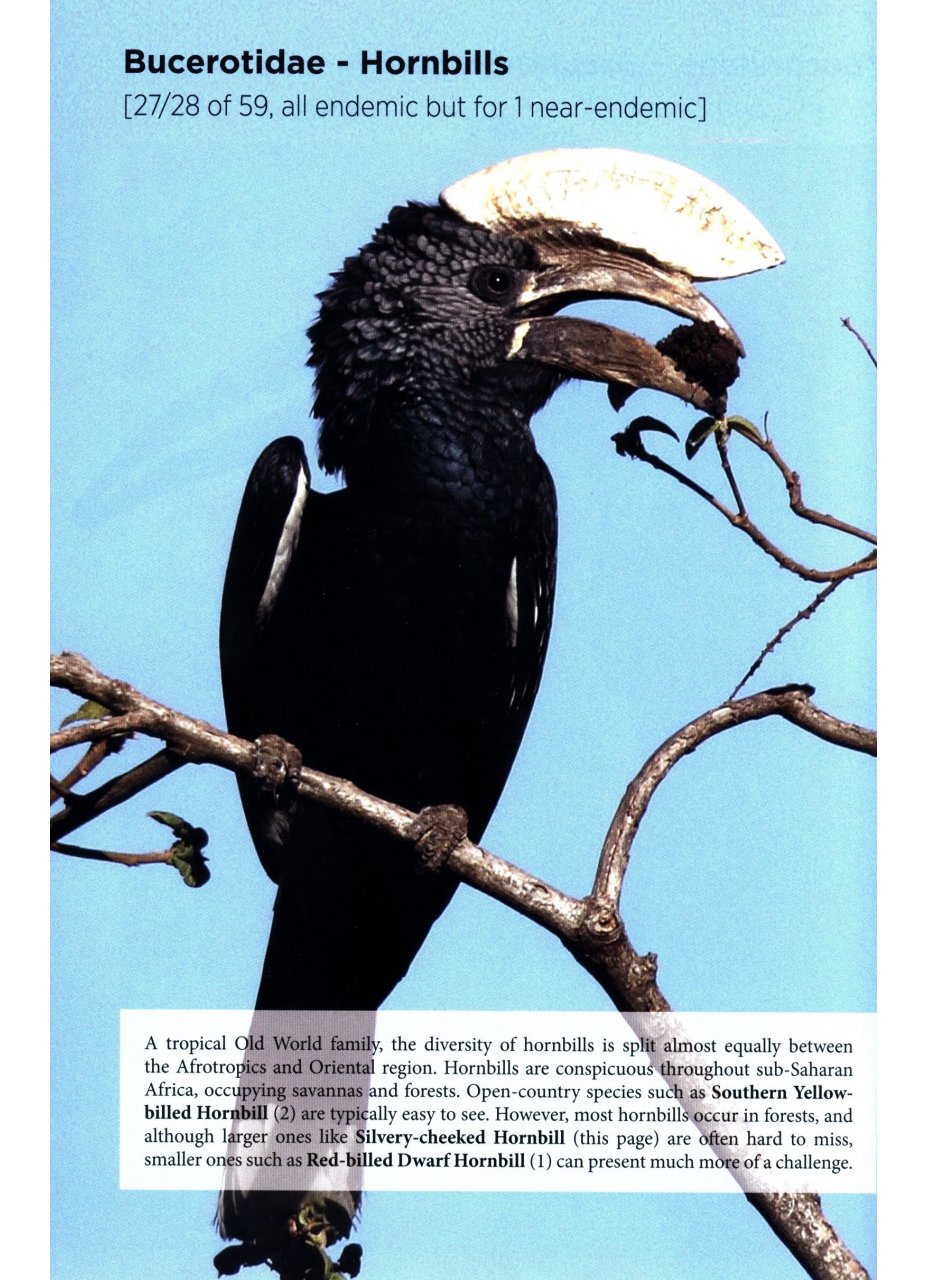

The Family Accounts section is designed for those who have the goal of trying to see representatives of all bird families in the region, as this is more achievable than trying to see all species. Africa is one of the richest regions globally for bird families and orders.

This approach may suit many people, and they would be encouraged by the large and splendid selection of colour photos of typical examples for each family, most of them taken by Tasso Leventis. These are reproduced from quarter page to double spread in size; I didn’t find the latter so appealing, as much of the photo is lost in the gutter (this is quite a fat book). Images vary from one per family to four or five, and there is a short paragraph characterising the family in which the photos are captioned.

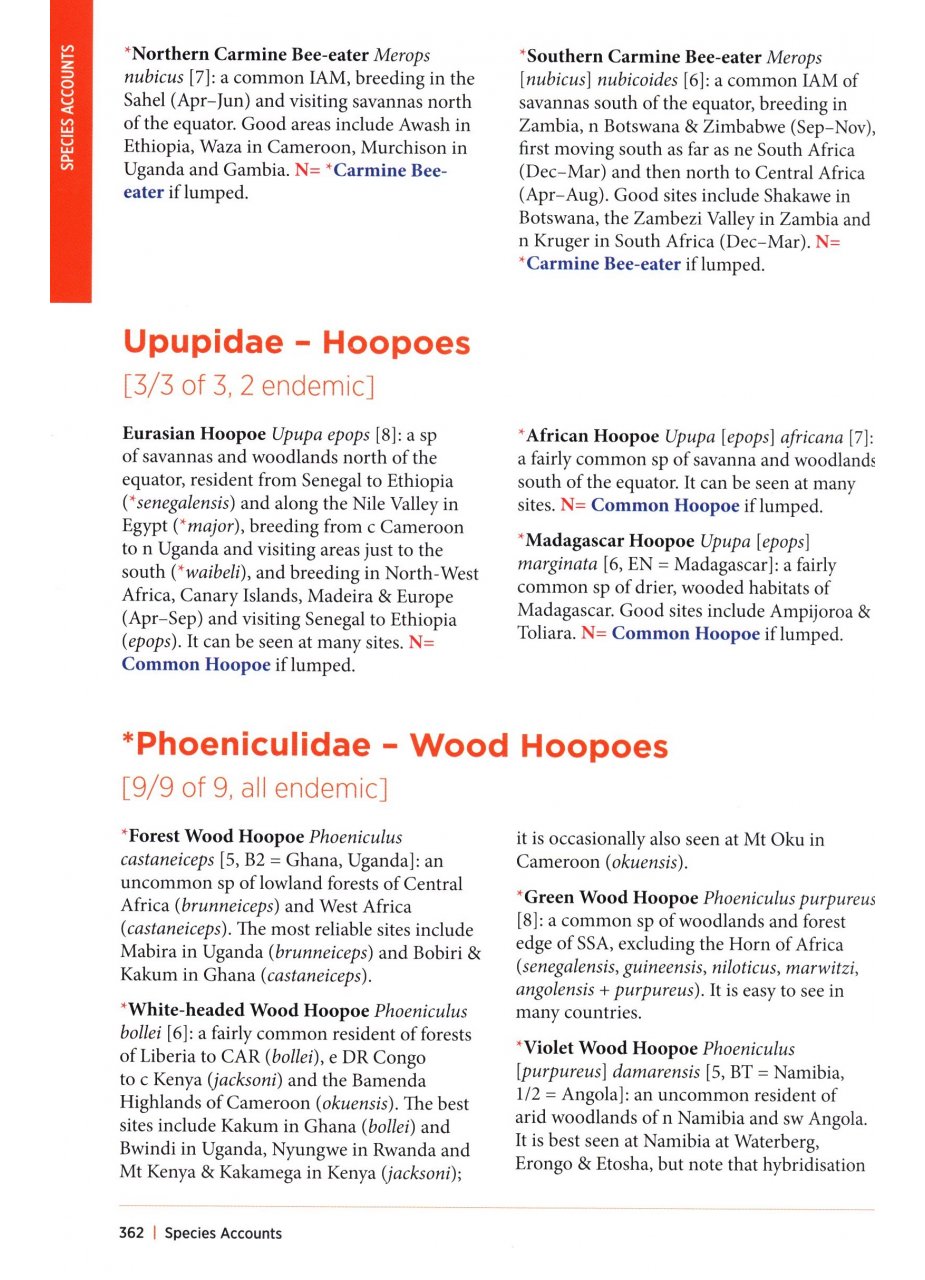

There is also a figure, which occurs again in the species accounts, denoting how many species occur in the region compared with the world total for that family. This sometimes confused me, for instance, when the range was ‘8/9 of 70’, until I found out that the IOC lists a world total of 70 and eight species in the region, though in the author’s opinion there are nine.

There are a number of splits and lumps, with names highlighted in green; the rationale is that it is worth drawing attention to those taxa that might prove to be good species. The images in this section are certainly mouth-watering for those unacquainted with African birds, but will be less relevant for hardened world listers.

The species accounts give brief details of distribution and where best to see each species. In keeping with the author’s penchant for rating things, there is a number for each species, from 0-10, indicating the ease or otherwise of seeing it. This section is probably the most useful for most people, giving a potted assessment of where and when they might see the bird in question.

Finally, there are the references, with which I have a few issues, and not only because I could not help noticing that my own paper in the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club about the genus Parmoptila is not included!

There are two sections, titled Country Accounts and Species Accounts and Other, listing many relevant field guides, handbooks, and travel guides. Curiously, Ash’s Birds of Ethiopia appears in both lists. However, although books such as Archer and Godman’s Birds of Somaliland (1937-1961) and Chapin’s Birds of the Belgian Congo (1932-54) are listed, there is no mention of, for instance, Bannerman’s eight volumes on Birds of West Africa, Jackson’s Birds of Kenya and Uganda or even seven volumes of The Birds of Africa, though the eighth, on Madagascar, gets a mention. Mackworth-Praed and Grant’s African Handbook of Birds, which was at my elbow for more years than I care to recall, and many other important titles could perhaps have been included.

Some journal references will be very hard to access, and this brings me to my main point about the references: if they had been numbered and listed either under the relevant country or species accounts, they would have been easily located. As it is, if you want to know what publications there are on, for example, Kenyan birds, you have to wade through about 14 pages.

There is a huge amount of information in this book which will be of great use to people planning birding trips to Africa, and I would not be surprised if its somewhat unusual approach does not serve as a template for guides to other parts of the world.