Yellow-billed Kite is among the most common and widespread birds of prey in Africa. This species is the Afrotropical counterpart to Black Kite, but a recent run of European records has led many to ponder the potential of a genuine vagrant reaching the continent – although considerable uncertainty surrounds the origins of these birds. While the escape risk clouds the picture across Europe, recent wanderers elsewhere mean the subject is worth approaching with an open mind.

Although treated by some authorities as a subspecies of Black Kite until recently, genetic studies indicate that Yellow-billed Kite should be considered as a separate, allopatric species. This is divided further into two subspecies: aegyptius, found along the Nile Valley into Egypt across to the south-west Arabian Peninsula, and parasitus, distributed throughout Sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar.

Yellow-billed Kite is one of the commonest raptors in Africa (Dave Williams).

Populations of nominate aegyptius are considered to be largely resident, nesting between December and June. Although parasitus is present in almost the entire range throughout the year, it is mostly an intra-African breeding migrant, with some birds making long intracontinental migrations. There are clear movements of migratory breeders to the south during the austral summer, with birds typically present in Southern Africa between July and March during the rainy season, with most arriving in August-September. Most individuals return to West Africa towards the end of the rainy season in March-April, though can be present throughout the year.

In adult plumage, Black and Yellow-billed Kites can be readily separated: Yellow-billed Kites have all-yellow bills, deeply forked tails, narrower wings and pointed wing-tips, with five long, fingered primaries (Forsman, 2019). The plumage is rufous-brown and uniformly coloured, with finer black streaking below than Black Kite. Juvenile Yellow-billed can be difficult to tell from juvenile Black, though the slightly different wing formula and moult timings provide some indication.

The parasitus subspecies of Yellow-billed Kite makes long intracontinental migrations (Steve Ray).

The vagrancy potential of the species is demonstrated by the occurrence of an adult in the Moroccan High Atlas at Tizi N'Tichka on 8 April 2008 and another reaching the Canary Islands near Arico, Tenerife, on 7 March 2020. The arrival of the bird on Tenerife was considered to be linked to a sandstorm that affected the islands at the end of February, which caused an unprecedented arrival of African birds (Rodriguez et al, 2021). Elsewhere in the Western Palearctic, Yellow-billed Kite has occurred as a vagrant to Israel on six occasions, all occurring between the months of January and July. More remarkably, one reached Cayenne, French Guiana, on 3 May 2023, becoming the first for the Americas. The latter coincided with a depression over West Africa, which may have favoured its Atlantic crossing (Claessens, 2023).

At first glance, Yellow-billed Kite appears an improbable vagrant to Europe. However, a curious pattern of records has begun to emerge in recent years. One, an adult of the parasitus subspecies, was present on the Dutch mainland near Lauwersoog on 11-12 April 2021 before continuing north-east, logged on Wangerooge, Germany, on 15-16 April and at Skagen, Denmark, on 2-3 May. It was last watched heading north-east across the Öresund towards Sweden, disappearing from view approximately 5 km out to sea. This adds up to a movement of almost 600 km in total. The 2021 bird was followed by an adult in Estonia the following year, at the migration hot-spot of Cape Põõsaspea on 25 April.

This adult Yellow-billed Kite flew over Estonia's premier migration hot-spot, Cape Põõsaspea, on 25 April 2022 (Annika Forsten).

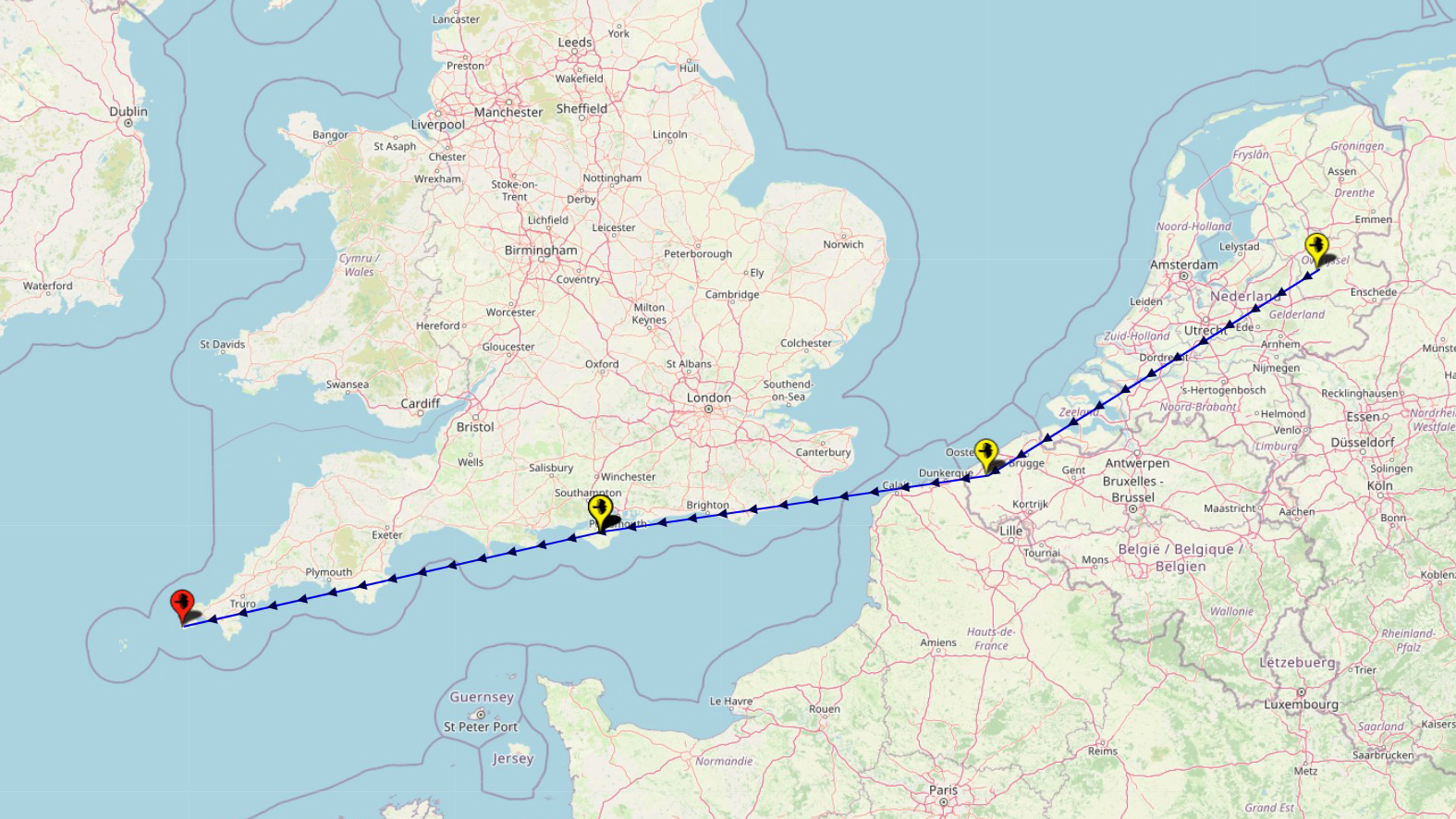

In Britain, the species has been recorded on two occasions. The first of these was an adult photographed in the company of Red Kites on the landfill site at Springfield Farm Quarry, Buckinghamshire, on 29 April 2019, although news only came to light in early 2023. Then, on 29 April 2023, an adult was photographed at Raalte, The Netherlands before relocating over 280 km WSW to Pervijze, Belgium, on 1 May. It later headed west, crossing the English Channel and lingering at Lynnbottom Tip near Newport, Isle of Wight, from 10-14 May 2023 – a relocation of some 290 km. On 15th, it was logged heading high south-east over Polgigga, Cornwall – a further westward movement of 320 km.

Map showing the movements of the spring 2023 Yellow-billed Kite (BirdGuides.com data).

Yellow-billed Kite's status in captivity is very much the elephant in the room when it comes to evaluating out-of-range records of the species. It is frequently kept in zoos and collections, with a number being featured in falconry displays across Europe. During April, an apparently wild Black Kite made repeated visits to the National Centre for Birds of Prey at Duncombe Park, North Yorkshire, where up to five Yellow-billed Kites are flown daily during flying displays. Both Yellow-billed and Black Kites are popular in bird-of-prey displays owing to their unfussy diet and aerial prowess. Their confident nature and willingness to co-operate for food means they will readily fly at close range past visitors with acrobatic, agile manoeuvres. While none are known to have gone missing in recent times, such information isn't always forthcoming. It is also possible that one or more individuals could have been wandering Europe for some time and the species is evidently able to roam over large distances.

Adult Yellow-billed Kites typically start to moult at the onset of breeding during the austral summer, so a 'scruffy' bird isn't completely unexpected in spring (Ashley Howe).

Nonetheless, the birds reported in northern Europe show no obvious signs of captivity – rings, leg bands or wing tags – and all appeared to be strong fliers. At least two of the birds engaged in long-distance movements of more than 600 km, and all occurred in a narrow date window between mid-April and early May. Both British records even frequented rubbish dumps in search of scraps alongside local Red Kites, a trait common with Yellow-billed Kites in Africa, as well as kites generally, and argued by some to be unlikely behaviour for a bird reared in captivity.

While all three birds show heavy plumage wear, this isn't unexpected in spring. Adult Yellow-billed Kites typically start to moult at the onset of breeding during the austral summer, which can vary in different parts of Africa depending on local breeding seasons (Forsman, 2016). In addition, moult of a tail begins later than primaries, which would account for significant tail wear.

This Yellow-billed Kite at Springfield Farm Quarry, Buckinghamshire, on 29 April 2019 is the first to be recorded in Europe (Tom (Fathom Falconry)).

It is perhaps noteworthy that all observations to date involve birds in spring and it is possible that some Yellow-billed Kites may follow Black Kites returning to Europe. Afrotropical species accompanying their Eurasian congeners north to Europe is a well-documented phenomenon. Records of Lesser Flamingo with Greater Flamingos around the Mediterranean Basin "fit geographical and temporal patterns that suggest the arrival of wild birds from Africa" (de Juana and Garcia, 2015), with the bulk of these (78%) first appearing between March and June. Similarly, records of both Rüppell's and White-backed Vultures from Iberia and North Africa are attributed to the increase of Griffon Vultures dispersing from and returning to Europe (Tonkin et al, 2022). The largely sedentary African vulture species mix with Griffons in the Sahel and get caught up in their pre-nuptial migration, bringing them north. Moroccan occurrences of Rüppell's Vulture have increased sharply, from a total of 11 records by 2011 to 103 by 2022 (El Khamlichi, R, and El Haoua, 2023). Another Afrotropical raptor, Bateleur, has occurred north as far as Turkey, Cyprus and Spain, with the last watched crossing the Strait of Gibraltar from Africa (Bird Cadiz). Afrotropical vagrants are increasing in Spain, a trend attributed to the northward movement of birds in response to a warming climate and milder Iberian winters (SEO BirdLife, 2017).

Some parasitus Yellow-billed Kite populations north of the equator, such as those along the Senegal River valley in Mauritania, move north outside the breeding season. These birds head north to the Adrar Plateau, just a short distance from the Moroccan border (Go-South). For this theory to have merit, however, you would expect to see additional records from Iberia and North Africa with spring Black Kites in the coming years, as observer awareness of this recent split increases.

Map showing movements of a GPS-tagged Rüppell's Vulture released in Portugal in October 2021 (Vulture Conservation Foundation).

When assessing the wandering adult of 2021, records committees in The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark placed the record into Category D (species that would otherwise appear in Category A except that there is reasonable doubt that they have ever occurred in a natural state). While there were no clear signs of a captive origin, the committees adjudged that "vagrancy potential to northern Europe has yet to be substantiated for this species, which is also regularly kept in captivity in several European countries" (Dutch Birding).

Ultimately, a cautious approach will be required with Yellow-billed Kite records in Europe for the foreseeable future, owing to both the lack of supporting records further south, such as in Iberia and North Africa, and the prevalence of the species in captivity across Europe. More information is required about the species' migratory behaviour and vagrancy potential, as the available dataset is small and the similarity to Black Kite means there is a possibility that it has been overlooked. Until that time, the odds are weighted towards European birds being escapes from captivity.

It could be presumed that a Yellow-billed Kite reaching north-west Europe – and Britain in particular – would be the longest of all long shots. That said, just where are they coming from? Hopefully, the coming months and years will provide an answer.

Yellow-billed Kite, Springfield Farm Quarry, Buckinghamshire, 29 April 2019 (Tom (Fathom Falconry)).

Yellow-billed Kite, Lynn Tip, Isle of Wight, 12 May 2023 (Ashley Howe).

References

Andreyenkova, N G, Starikov, I J, Wink, M, Karyakin, I V, Andreyenkov, O V, and Zhimulev, I F. 2019. The problems of genetic support of dividing the Black Kite (Milvus migrans) into subspecies. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding 23: 226-231.

De Juana, E, and Garcia, E. 2015. The Birds of the Iberian Peninsula. Helm Identification Guides, London.

El Khamlichi, R, and El Haoua, M K. 2023. Première mention du Vautour charognard Necrosyrtes monachus dans le nord du Maroc. First record of the Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus in Northern Morocco. Eléments d’Ornithologie Marocaine: eom23051.

Forsman, D. 2016. Flight Identification of Raptors of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Helm Identification Guides, London.

Rodríguez, B, Siverio, F, and Hernández, J J. 2021. First record of Yellow-billed Kite Milvus aegyptius for the Canary Islands and Macaronesia. The Bulletin of the African Bird Club 28: 238-240.

Van den Berg, A B. 2009. Yellow-billed Kite in High Atlas, Morocco, in April 2008. Dutch Birding 31: 172-173.