This is Part II of Jack Wylson's Papuan adventure. Read Part I here.

After a month in Papua New Guinea, we arrived with more than a touch of apprehension at the Indonesian border. We planned to cross to the city of Jayapura in West Papua, but the border had been closed for the last few days due to civil unrest in the region. We had no idea if we could get across. Having spent a large proportion of the past month in transit, or waiting for transport (sometimes for days) by roads and quays, the idea of being turned back didn't bear thinking about. To get to Jayapura otherwise we'd have to fly all the way back to Port Moresby, then to either Australia or Singapore, then to Jakarta, then on to Jayapura! I was sweating more than usual in the 35° heat as we approached immigration.

After being prodded and poked for signs of Swine Flu and with a huge sigh of relief, we successfully crossed into West Papua.

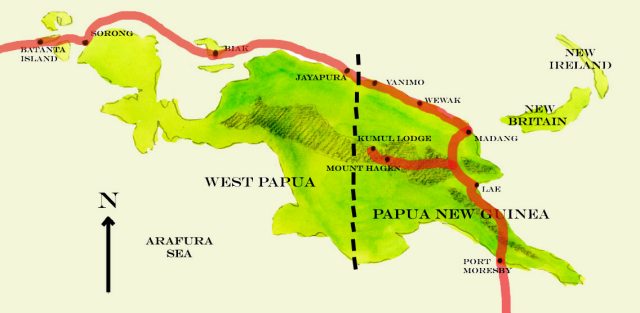

Jack's route through Papua New Guinea (Map: Jack Wylson)

First impressions were horrific. The rainforest suddenly vanished without a trace. The wooden shacks with banana-leaf roofs that we were so used to in PNG were replaced with concrete houses, or plank huts made from jungle hardwoods. We passed several sawmills. It was sickening. Indonesia is obviously heavily exploiting the land, which is not even truly theirs. Also the local Papuans are being ousted by the Indonesians who, in a directive known as Transmigrasi, are being given incentives to relocate from crowded areas of the country (such as Java — the most heavily populated island on earth) to under-populated areas such as West Papua. It is also allegedly an attempt to dilute the Papuan culture — hence the civil unrest. Excuse my rant, but coming from what is almost a wildlife utopia in PNG, West Papua illustrated exactly what PNG is isolated from — economic development to the detriment of the environment.

First stop out of Jayapura was Baik Island where we had a slight setback. Although I'd been taking my prophylactic drugs (Malarone if you're interested), I suddenly came down with a fever that turned out to be malaria. Fortunately I was only incapacitated for a couple of days, but I missed seeing the Biak endemics I'd hoped for, and it wasn't until we arrived at Sorong that I felt fit enough to do some serious birding.

The Raja Ampat islands lie off the coast of West Papua, and by all accounts they are some of the most spectacular tropical islands in the world, particularly when it comes to diving. Two of these islands, Batanta and Waigeo, are also home to endemic Paradisaeidae: the Red Bird of Paradise and the appropriately named Wilson's Bird of Paradise. Sorong is the nearest city on mainland West Papua, and it was here that we tried to hire a boat and guide to visit Batanta Island, the nearest of the Raja Ampats.

Down at the quay we asked the local skippers if we could charter a vessel and soon found a man who spoke some English. He said he could not only organise a boat for us, but also find us a guide to find the Cenderawasih (that is Indonesian for Bird of Paradise). After some intense haggling we secured a boat and guide for two days for a reasonable price. The plan, so far as we could understand, was to go over, do some snorkelling, find the Birds of Paradise, stay over in the village, then return back the next day. It all seemed too good to be true.

Next morning, we met our friend down by the quay at sunrise. We climbed into his small motor canoe, which was being manned by some young men, none of whom spoke English. To our surprise, once everything was loaded our friend jumped off the boat and wished us well — we had been expecting him to come along.

"What about our guide?" I called after him.

"He will meet you there", he said. We hadn't expected this.

"What's his name?", I called as we cast off. I could just make out the reply.

"Anthony...."

After some early engine trouble where we questioned the ability of our young crew, we got underway. We were slightly concerned that we'd lost our only English speaker, but expected Anthony to be waiting on the shore for us when we arrived.

It took us about four hours to reach the village on Batanta Island. Unlike the mainland, the islands we passed were covered with thick rainforest, just like the lost world. There was not a sign of human habitation in sight until we saw the village jetty. We moored up, and peering into the water off the jetty: the visibility was mesmerising. The bottom, five metres down, was as clear as if the water were made of glass. But where was Anthony? He wasn't waiting on the jetty for us. In fact, the village was very quiet: there were just a handful of huts and a couple of children playing on the beach.

Batanta (Photo: Jack Wylson)

We went off to try and find our guide and were led to a small house and invited to sit down and wait. After a few minutes a smiling old man arrived.

"Hello! My name is Alfonse." I was relieved to hear some English, albeit with a very strong accent.

"Hello," I replied, "We are looking for our guide — his name is Anthony." Alfonse's brow furrowed, he scratched his eyebrow, looking deeply perplexed.

"Anthony is did," he replied. I wasn't sure what he meant.

"Did?" I repeated.

"Yes, did." The penny dropped. Anthony is dead. I hadn't expected that...

"He did in February," Alfonse continued. It was now late May. News obviously travels slowly in these parts. I tried to ask what he had died from, suddenly feeling guilty that I knew nothing about our guide-not-to-be other than his name. Alfonse didn't seem to understand and continued smiling. A few more people arrived. I felt sorry for the deceased, but at the same time, I felt suddenly concerned that Anthony might be the only one who knew where to find the birds. I explained that I was looking for the Cenderawasih and asked if anyone could guide me. I tried to clarify that there are two kinds of Cenderwasih I wanted to see, and began drawing a diagram, one with a long tail, under which I wrote 'RED'.

"Yes, yes. Red", Alfonse was smiling and nodding. Then for the second I drew a bald head, annotated it with an arrow and wrote 'BLUE'. Again Alfonse nodded.

"Yes, yes, blue. Vilson's..." (they have trouble saying 'W's in Papua, like Germans). He took the pen himself.

"This one OK" he said and drew a big tick next to my Red Bird of Paradise diagram. "And, this one OK" he said and did the same next to Wilson's. Things were looking up.

Our new guide was called Yahuda. It was agreed that first we would go snorkelling, then we would look for the birds. I would have preferred it the other way round, but I didn't argue. We took the boat round a couple of bays from the village to a beautiful beach and jumped into the water. It was incredibly clear, but there was no coral. I swam around searching, and came across a small clump of corals not much bigger than a beach ball. It was surrounded by hundreds of tiny fish of several species. There were also various different species of coral. It was small, but it was full of life, and so bright. I was just thinking to myself, 'that is the best coral I've ever seen', when Yahuda joined us in the water. He didn't speak any English and was eyeing us strangely. Gesturing for us to follow him, he swam over towards the edge of the bay. We followed and soon realised our stupidity. The edge of the bay was lined with the most stunning coral imaginable. It made every reef I had ever seen before look like a load of dull rocks. This was coral as it is supposed to look, a rainforest of the sea, bursting with life in every direction. There were countless fish of all shapes and colours. Each species seemed to group in huge shoals of unimaginable numbers — millions of them. One species formed a massive ribbon-shaped shoal that, despite twisting and turning and tangling, never lost its ribbon shape. There were fish literally every colour of the rainbow.

Whilst we were snorkelling, a small party of Blyth's Hornbills flew over grunting, their wings swooshing like pterodactyls. I got out of the water — we'd been in for hours — then climbed onto the roof of the boat to try and get a vantage point to see over the forest. Sulphur-crested Cockatoos were screeching loudly. In the distance a Palm Cockatoo flew over the tree-tops, a bird I have long wanted to see. Again, it had a prehistoric look to it. This island really did feel like the lost world.

The jungle was impenetrable from the beach, except for where a small stream ran out. The crew were busy catching fish with their bare hands, which they were cooking on a small fire for lunch. I wandered up the stream exploring and found a gem: a Little Kingfisher catching the fish being scared upstream.

Back at the village, we were shown to our accommodation, a stilted hut with a wicker mat to sleep on. At 3pm, Yahuda and I set off into the jungle. We left the village and walked through some banana plantations. A group of three magnificent Palm Cockatoos eyed us from the top of a vast tree. Eclectus Parrots flew to and fro squawking loudly. We were soon entering the dense jungle on the outskirts of the village. Yahuda stopped by one of the first trees we came to and said quietly 'Cenderawasih...' Surely not, I thought: we were only a stone's throw outside of the village. I looked up into the empty, but spectacularly huge, tree. He had to be joking: there wasn't a bird in sight. I wondered if Yahuda knew what he was doing. Then there was a movement above; it was a couple of Spangled Drongos, but with them was something new — not a Bird of Paradise, but a Rusty Pitohui. This I was excited to see, as they have recently been discovered, along with two other species of Pitohui, to be the world's only poisonous birds. They actually have toxins in their feathers. The foraging party moved through, once again leaving the tree empty. Maybe Yahuda thought all birds were Cenderwasih? My confidence in his ability was waning. Suddenly, out of nowhere, came a loud chorus of comic-sounding calls: "whaa, whaa, whaa", almost duck-like. The sound was approaching through the canopy. Now there were several birds in the top of the tree. I craned my neck to see them. If you think looking for a Pallas's Warbler in the top of a Holm Oak gives you neckache, this is another league of agony. I caught glimpses of tails quivering and wings outstretched, heads poking round branches, all the time accompanied by the idiotic display calls. The Red Bird of Paradise displays communally, and there were probably at least ten birds up there in the gods. It was an amazing experience to be directly below such a cacophony of displaying birds, despite the neckache. I managed to get some good views before the action tailed off. At that point my neck said 'no more' and the swarm of mosquitoes around us became unbearable.

'Wilson's...?' I said to Yahuda. He nodded and pointed uphill. We set off, directly up a mountain, following the faintest of paths. Yahuda was setting a fair pace. He was wearing a woolly hat and long sleeves, but didn't have a bead of sweat on him. We heard the sound of Hornbills swooping loudly over us, unseen above the canopy. We'd been walking for some time, when suddenly the path levelled out to a slightly more comfortable incline. I caught sight through the trees of the height we had climbed to. We were right at the top of the mountain now, the village a collection of tiny specks below. We pressed on and came abruptly into an immaculate clearing, at the centre of which was a perch. Yahuda showed me to a makeshift hide at the clearing's edge. It was a large palm leaf propped up with a couple of stakes. The fronds were parted slightly in the centre, just enough for a pair of binoculars to poke through. I squatted down behind it. Yahuda was busy breaking off pieces of a fern leaf he had found and scattering them on the bare earth, in what was surely the centre of a display arena. As soon as he began there was an extremely loud 'chaw, chaw, chaw'!. Wilson was watching.

Yahuda came and hid behind the palm leaf with me. The sound grew closer: Wilson obviously didn't take kindly to having his display site violated. I waited, hardly daring to breath. Most of the other Paradisaeidae I'd seen had not been close. This time I could hardly be any closer — the display perch was just 10 feet away! Wilson's disgruntled outbursts were getting louder, but he was still out of view. Then, out he popped. He landed on his perch and sang loudly, scolding the reprehensible fern leaves. His bright blue and startlingly bald head, criss-crossed with what look like black veins, was actually considerably more attractive than it sounds. He was close enough to study every detail of his plumage. The two projecting spiral-shaped tail feathers were very strange: they looked solid, as though they were made of Bakelite plastic, not feather. There was a clashing yellow, semi-circular patch on the nape and bright red on the mantle, spilling onto the tertials. All in all, he was beautifully gaudy, and so small, just Starling-sized.

Wilson's Bird of Paradise (Illustration: Jack Wylson)

There was a rattling sound, like a cartoon skeleton's teeth chattering, and he was on the ground. Was that the sound of his tail feathers jangling, or a flight call?

He set about tidying up, grabbed the fern pieces, then tossing them away from his perch, working round in a circle. He was evidently scrupulously tidy. After his first circuit he continued, throwing the leaves even further out of his precious arena. Then finally he went round once more, throwing them from the very edge of the clearing out into the jungle, where they could no longer offend. He flew back to his perch, sang defiantly and hissed, then with a skeleton-teeth jangle he flew back into the forest.

Yahuda jumped up, and before I could say anything, he was again throwing the fern leaves down in the freshly cleared arena. This would surely enrage poor Wilson. Five minutes passed, then he returned noisily and performed the same ritual. He was a very proud bird.

Suddenly a female dropped in. This caused an uproar of singing from Wilson, who had by then finished tidying. But, as is so often the case, the female was soon gone. Wilson looked bemused.

Once more, when Wilson again returned to the darkness of the forest, Yahuda stood up to scatter the leaves. I stopped him, feeling we'd humoured the poor bird's fastidiousness enough. It was also getting towards twilight. Silently we crept out of the hide and back down the path. I was totally captivated by the encounter I had just had. I felt extremely privileged as I stumbled down the mountain, trying to absorb everything I'd just seen. The path was very treacherous. I fell over four times in my absent-mindedness; my head was whirring. Suddenly Yahuda — who had been as sure-footed as a mountain goat all afternoon — jumped backwards and fell into me. As he did so a pale bluey-white coloured snake about 5 ft long sprang from the path into the air, and slid off down the mountain. It was gone in an instant. Yahuda's face was pale. I mimed slitting my throat with my hand. He nodded gravely...

It was almost dark when we got back to the village. A Rufous-bellied Kookaburra was calling from the trees next to our hut. The sunset was beautiful. I thought about Wilson, up on the mountain-top above. Apparently his blue head is so bright it can be seen in the dark...