Breeding numbers of Eurasian Curlew are decreasing across Europe, including the large Russian strongholds. This situation led the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) to organize an international action plan for the conservation of the species. Since the hunting ban in 2012 in Ireland, France is the only country where Eurasian Curlew is legal quarry. In a 2019 publication the government proposed a quota of 5,000 kills, while the consulted scientific experts recommended a temporary ban.

Meanwhile, French scientists and wildlife NGOs had started to study movements of curlews wintering in western France with GPS tags, to document migration connectivity, while attempts had been made to also capture and track breeding curlews. Eurasian Curlew is red-listed as Vulnerable as a breeding species in the country. Pierrick Bocher of Université de La Rochelle started a programme called Limitrack in 2015 in association with the Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO, the French BirdLife partner), tagging four wader species in protected areas along the Atlantic coast. One of the main ringing sites is Moëze-Oléron NNR, managed by LPO. Rangers of the reserve have a solid experience in catching and ringing shorebirds; they are indeed the referents for the CRBPO national ringing scheme when it comes to shorebirds.

Eurasian Curlew is one of Europe's best-known waders, yet it is in decline across the continent (Andrew Steele).

Moëze-Oléron NNR

At the heart of the straits of Charente, called the Pertuis Charentais, this reserve is an important international site for migratory birds. The site's distinguishing feature is the combination of marine and terrestrial habitats, including eelgrass beds, mudflats, sandy beaches, rocky shores, seafood farms, marshland polders, lagoons and saltmarsh.

Since 1985, management of one polder was committed to monitoring water levels and salinity in ditches, lagoons and marshland areas. This habitat patchwork offers a range of settings which appeal to a large number of species. It's a highly treasured national heritage site due to the volume of wildlife present, as well as the presence of restricted-range species for whom the area plays a crucial role. These include waterbirds, European Eel, European Otter, amphibian voles, European Freshwater Turtle, plus other reptiles, amphibians and insects.

An aerial view of a section of Moëze-Oléron NNR.

Equally, the pastoral maintenance of the grassland is focused on conservation concerns regarding nesting birds or grazing waterfowl. Adjoining the 220 ha classed as national nature reserve lies a further 100 ha owned by the Conservatoire du Littoral (a coastal conservation authority), which is also run according to state-approved management supervision plans. The acquisition and sharing of skills and knowledge are as much responsible for the successful conservation of such biodiversity, as is learning how to share good practices in order to sustain a national nature reserve.

Two times each year, birds bound for the likes of Siberia, Greenland, Iceland and Britain, fly across Europe to reach their winter or breeding grounds. Moëze-Oléron is on their itinerary and offers an important stopover, allowing them to stock up on vital resources. The reserve is protected by regulations, and is the only site in France with three intertidal zones under full protection. Waders are extremely sensitive to disturbance, which can have a damaging impact on their physical condition, and capacity to feed and rest. In this region, with its high tourism and hunting activities, they are constantly on the lookout for peaceful resting places; being completely out of public bounds, the reserve allows birds to feed and rest undisturbed.

The Limitrack programme

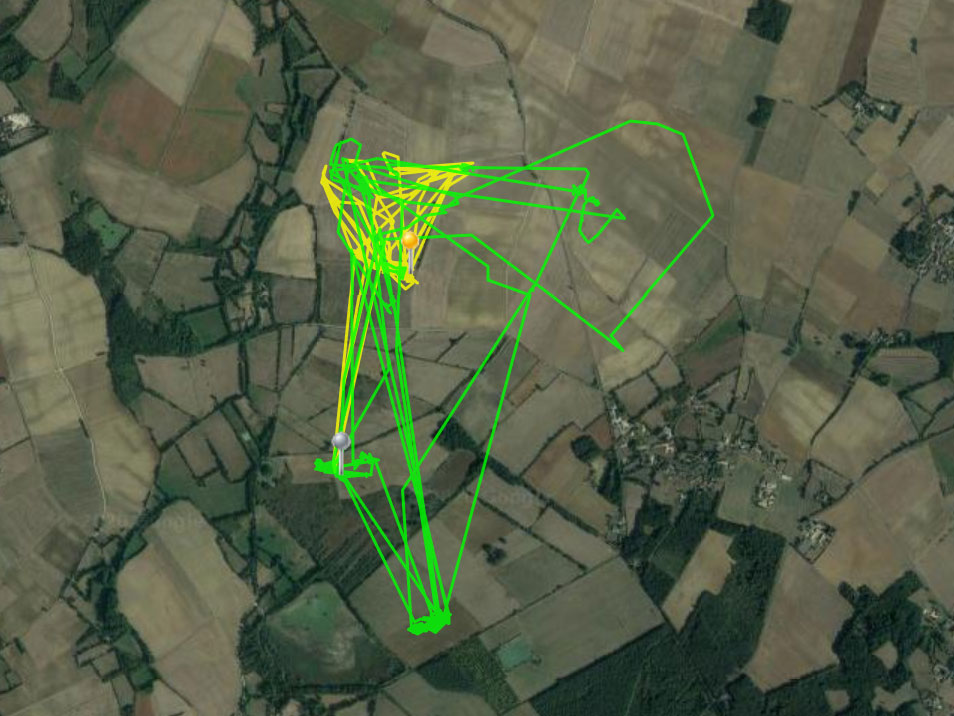

Limitrack aims to understand the various winter (August-April) survival strategies of curlews and four other species on the Charente coast around the city of La Rochelle. Being a prime area for wintering shorebirds in France, it's also crucial for the conservation of these species at an international scale. It began in October 2015, when the first GPS loggers were deployed at Île de Ré. Between winter 2015-16 and winter 2018-19, 27 curlews were tracked with GPS loggers, producing a position every 30 minutes in winter and, for some of them, also during migration and the breeding season.

We found that individual curlews were extremely site-faithful in winter, favouring the same small areas for feeding. Each bird appeared to specialize on very few feeding habitats, but a diverse array of habitats was used by different individuals, from rocky shore to saltmarsh. This study thus demonstrates the high specialization of individual non-breeding curlews relying on specific foraging grounds and habitats, with important implications for the conservation of this species.

It transpired that most of the birds tagged in the La Rochelle area spent the breeding season in Russia. Individuals tracked on migration showed high fidelity to both wintering and breeding sites. Further analysis of the data is underway and will complete knowledge of the species’ wintering habits, as well as explore further migration and the eastern-breeding birds.

Limitrack's findings are immediately made available to reserve managers and stakeholders, in order to improve the environment and protection of the species on a regional scale. The data will also be valuable for assessing the impacts of hunting on this species in France.

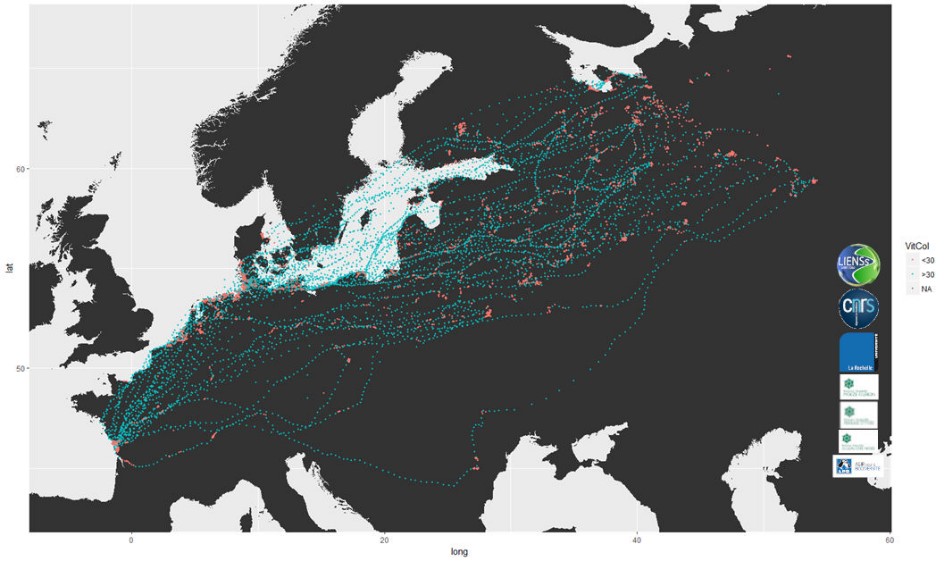

Eurasian Curlew migration routes collected by Limitrack between 2015 and 2019.

Starting a collaborative scheme

In 2020, a new coordinated national tagging program for Eurasian Curlew began, involving the University of La Rochelle, LPO, former ONCFS (national hunting office) now integrated in the larger OFB (French Office for Biodiversity) and other nature protection NGOs, coordinated by Frédéric Jiguet at MNHN-CRBPO. This collaboration started with the tagging of 11 wintering curlews in Charente-Maritime at the end of February 2020, and of five breeding birds in Deux-Sèvres, western France, at the end of March.

To date, all curlews are alive, wearing their tags and transmitting location data. Here we share initial results obtained from these birds, and hope that this may stimulate potential larger collaborations with other European countries. It is hoped that further tags will be deployed this spring in Estonia and Finland, using the same tags and harnesses as used by the French team.

Eurasian Curlew, waiting for tag equipment, after metal and colour ringing. This bird left western France on 12 April, and flew right over Paris before reaching western Russia.

A fitted tag with solar panel; the silicone harness material is also visible.

Migration connectivity

In 2015, curlews were captured during the core winter period (October-December). Of the 10 tagged birds, eight subsequently bred in European Russia, one in Belarus and one in Finland. In 2016, five tagged birds bred in Russia (three), Belarus (one) and Germany (one). In 2019, seven birds were tagged and all of them bred in European Russia. In 2020, curlews were caught later in the season, closer to the first departure dates from wintering sites. Of the 11 tagged birds, three left in early March to reach breeding grounds in Belgium, Germany and Austria, while six more departed in mid-April for Finland (two) and European Russia (three). One was still lingering in the Wadden Sea in early May.

Preliminary understandings – to be interpreted cautiously given the sample size – are that:

- Nine of the 11 curlews we caught were probably adults, at least in their 3cy, as 2cy should stay on the wintering grounds to spend their first summer. This means that a very large proportion of the population is made of mature individuals, at least at the end of the winter;

- Half of the adults present at the end of the wintering periods came from populations breeding within the EU, not from easternmost Europe. Indeed, one might expect a large proportion of Russian breeders to use an eastern rather than western flyway. Further tagging in the coming years will try to understand if birds present during different periods of the winter have different origins. One possibility is that early winter groups are mainly made of 1cy birds from Russia, and that hunting modifies this composition as the winter progresses.

Migration elevation and speed

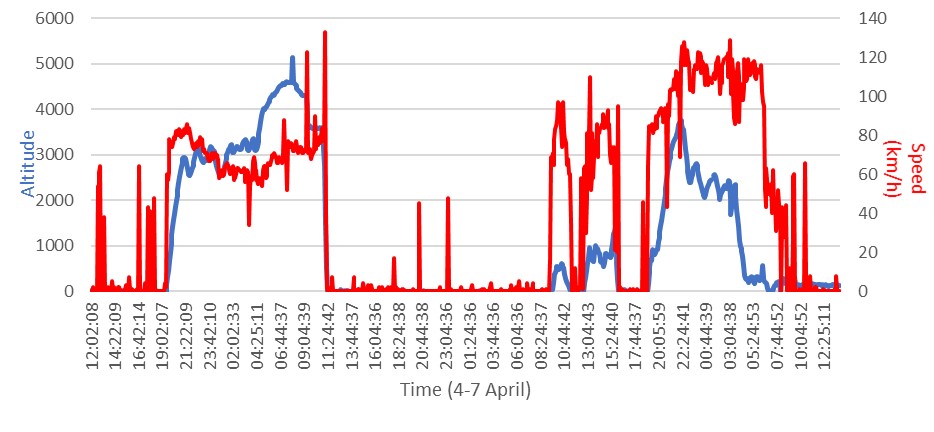

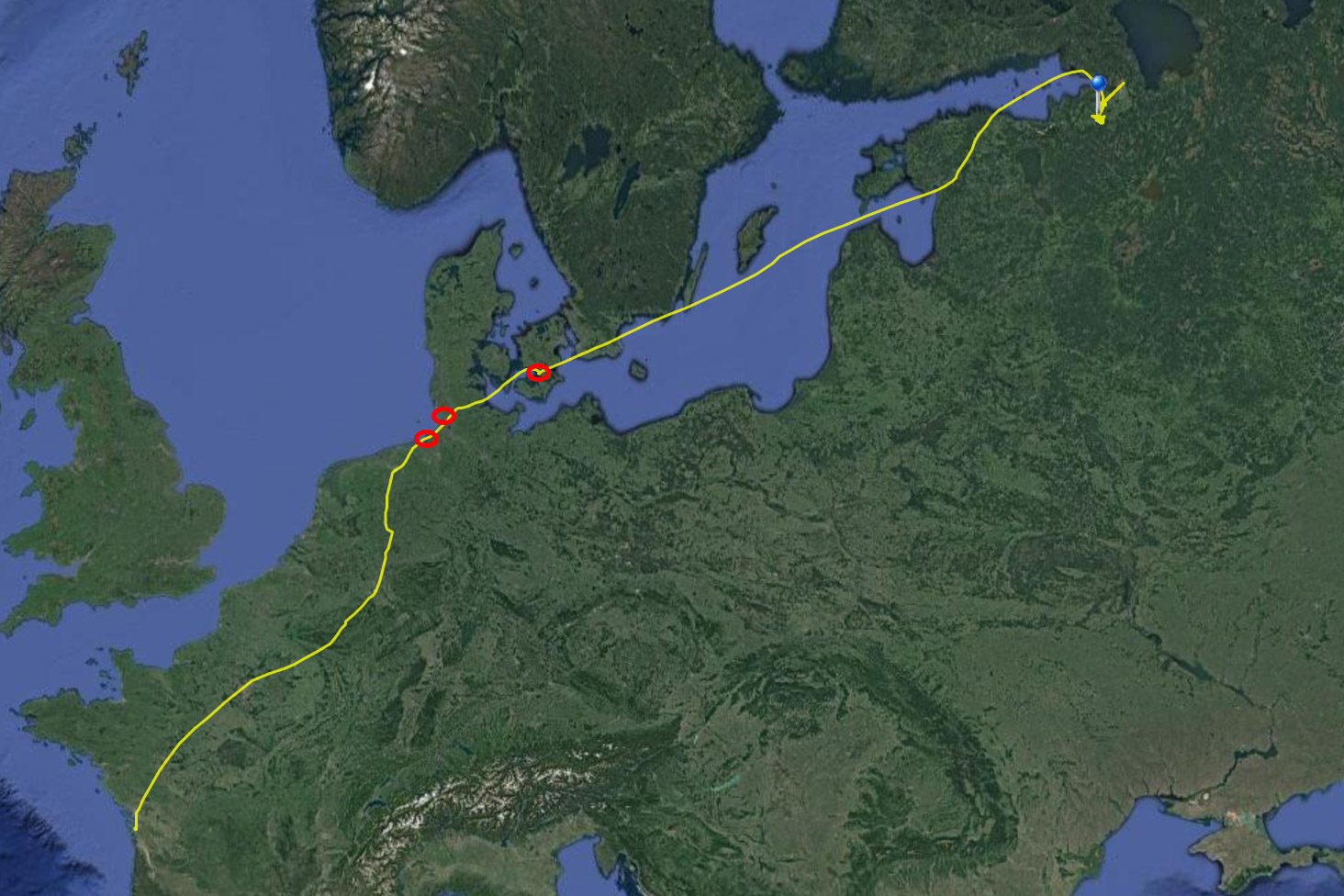

All tags can be reprogrammed at distance, so that we tried to record 3D locations every five minutes, while the accelerometer provided progresses in all three dimensions and flight speed. Migration tracks can then be plotted on a map, and altitude and speed on a graph, as illustrated below for the male curlew '200186', which reached its breeding grounds south of Saint Petersburg in three days.

This bird made three stopovers during his journey. A first stop lasted nearly 22 hours on the mudflats south of Emden, in the Dutch Wadden Sea, close to the German border. The male then briefly stopped again in the Wadden Sea, before progressing across the Danish peninsula and stalling again for a few hours south of Copenhagen. The last flight, over southern Sweden, the Baltic Sea and Estonia, was direct, at average altitudes (mainly between 2,000 and 3,000 m) but at high speed, probably benefiting from tailwinds, with an average speed reaching 115 km/h. The first part of the migration, over western Europe, was performed at higher altitudes, averaging over 4,500 m over Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands, but at lower speed, between 60 and 80 km/h. From the graph, we can see that when the bird drops down from the sky, the speed can double within a few minutes (see drops in altitude corresponding to peak in flight speed just before the first stop, when the bird descends to land near Emden).

Flight altitude and speed of Eurasian Curlew '200186', departing Charente-Maritime, France, to reach its Russian breeding grounds.

Flight path of Eurasian Curlew '200186' between Charente-Maritime, France, and breeding grounds near St Petersburg, Russia. Red rings mark stopping points.

A simultaneous departure

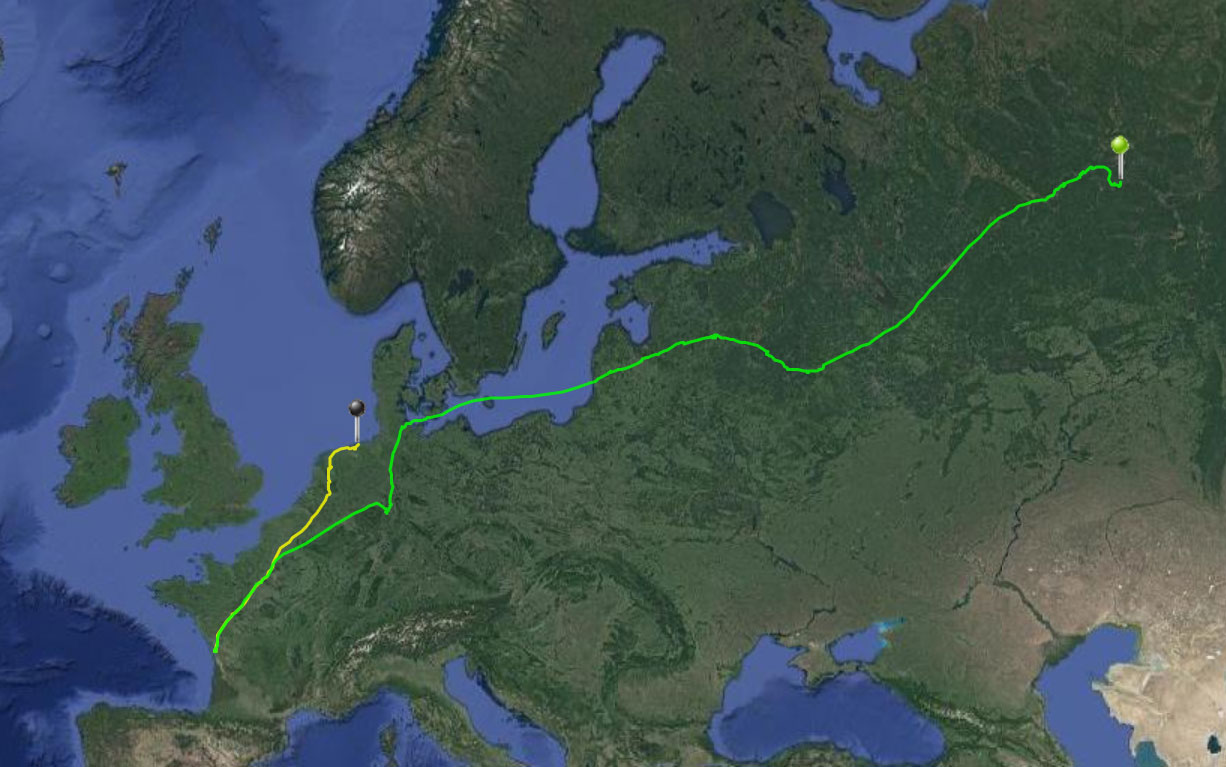

Two curlews that departed at sunset of 17 April started their migration together, but their routes split after a stopover in northern France, which lasted two hours and a whole day for the respective individuals. The first individual made a further stopover in Lithuania, before heading to Russia. The other was still lingering in the Wadden Sea on 1 May.

Two Eurasian Curlews that left French wintering grounds together, but then split while on migration.

Relocating tagged birds on their breeding grounds

By contacting ornithologists in the European countries where some of the curlews lingered, we were able to obtain field confirmation of the presence of some individuals. The bird in Austria was paired and defended a territory close to the Hungarian and Slovakian borders, and was photographed mid-March by Franz Eibl. Thanks to Norbert Teufelbauer for making the link.

In Germany, Franz Bairlein alerted the National Park rangers on the Wadden Sea island of Spiekeroog. The bird there is using a small area of saltmarsh and dunes; its nest was found on 28 April by ranger Lars Scheller, who managed to photograph it earlier in the month.

Eurasian Curlew nest on Spiekeroog, Germany, and (inset) the ringed adult (Lars Scheller).

In Belgium, a close eye is being kept on the bird in Flanders. The bird is paired, and the nest has been located.

A French-ringed Eurasian Curlew in Belgium. This bird is paired and its nest was found in early May (Norbert Goossens).

Tracking breeding birds

Part of the programme is dedicated to the tracking of breeding birds. When lighter tags become available, notably the 5-g Icarus tags, we plan to tag fledglings to study their survival and dispersal. But right now, we decided to capture and tag breeding adults, testing a low-invasive capture method in a breeding population of western France, implemented in the field by CRBPO ringers working for the local nature protection organisation GODS (Groupe Ornithologique des Deux-Sèvres). We were reluctant to capture breeding birds at the nest, given the poor conservation status of the species. We therefore tried another method, using classical mistnets early in the season, before egg laying, when we expected males to be particularly aggressive towards intruders. Despite the lockdown, ringers were allowed to perform their fieldwork, and the capture methods proved highly efficient, as five adults were captured and tagged within 24 hours. The first tracks revealed that some pairs are highly mobile, so that previous estimates of population sizes were slightly overestimated.

Tracking breeding curlews allows to model home ranges, study habitat use and locate nests to ensure protection against agricultural works. It's also amazing to see how a male and a female of a pair are 'synchronized' in their movements. Next winter, such birds will also give clues as to where French breeding birds go in winter.

In Deux-Sèvres, local protectionists have been monitoring breeding pairs in order to detect and protect nests and increase breeding success. Camera traps are used to identify causes of breeding failures, fences erected to protect nests, and chicks will be ringed from 2020 onwards to better estimate breeding success. It is hoped that these birds will help understand where French breeding birds migrate in winter.

Camera trap monitoring a curlew nest in Deux-Sèvres, western France. Nest destruction by agricultural works is a major cause limiting population dynamics (GODS).

Local ornithologists try to detect and protect curlew nests by placing fences in Deux-Sèvres, western France, April 2020 (Etienne Debenest).

Recently hatched chicks at a protected Eurasian Curlew nest, Deux-Sèvres, western France, April 2020 (Etienne Debenest).

From 2020 onwards, French breeders and French-born chicks will be ringed with blue darvic with a white three-digit code, starting from 001.

Conclusion

In 2021, we plan to extend the tagging to other French breeding populations in Val de Saône (with OFB partners Charlotte Francesiaz and Emmanuel Joyeux, where are the main breeding strongholds of the species in France), in Brittany (with Bretagne-Vivante) and in Normandy (with Groupe Ornithologique Normand).

We also hope to continue to provide tags to foreign partners, as we did in 2020 in Finland and Estonia, and are open to any collaboration to extend this initiative into a global framework.

We are convinced that ongoing research will help acquire the necessary knowledge on global migration connectivity in this species, as well as understand the dynamics of French breeding populations.

References

Brown, D J. 2015. International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata arquata, N a orientalis and N a suschkini. AEWA Technical Series No 58. Bonn, Germany.

Mischenko, A. 2020. Meadow-breeding waders in European Russia: main habitat types, numbers, population trends and key affecting factors. Wader Study 127(1). doi:10.18194/ws.00178