Touching down in Port Moresby, I certainly wasn't expecting a big, smoky metropolis but, from my window seat, the place appeared more of a village in a swamp than the largest city in the South Pacific, and capital of Papua New Guinea. Outside the tiny airport I climbed into the first vehicle in a dubious-looking taxi rank, an ancient Toyota Corolla. It was covered in dents and scratches and the windscreen looked like it had been retrieved from a car wreck: an intricate latticework of cracks. My friendly driver smiled and skilfully spat a glop of red betel-nut juice and saliva through the open window. He started the engine with a screwdriver and we trundled down the road with what sounded like the entire bottom of the car dragging along the ground. We ran over a pathetic-looking dog — bang — yelp! — crunch. This was to be a normal day in PNG...

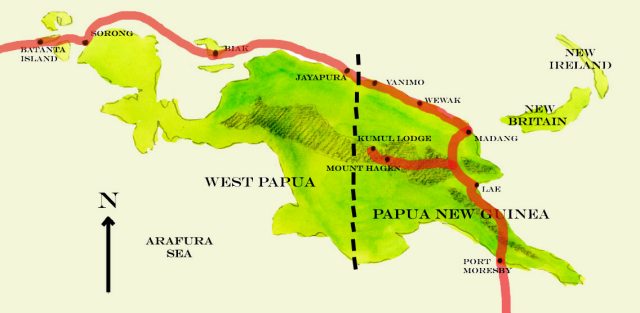

Jack's route through Papua New Guinea (Map: Jack Wylson)

Why was I here? The city's reputation is hardly glowing. Considered one of the world's worst and most dangerous, with a murder rate 23 times that of London, it even pips to the post the likes of Lagos (Nigeria) and Karachi (Pakistan) for the less-than-coveted title of 'world's least liveable city'. I'd been advised not to walk around the city after dark, and in several suburbs (such as endearingly named Kila-Kila) it is recommended to not walk around at all — even in daylight. Needless to say, I didn't come to PNG for its capital city.

Visiting New Guinea had long been a pipe dream of mine: a place so excitingly remote, exotic and uncharted that I had barely dared believe that I might one day visit, and here I was. It felt like I'd arrived at the end of the earth.

Apart from the boundless jungle, the anthropological intrigue, and the undeniable adventure, there are 44 members of the Paradisaeidae (that is the Bird of Paradise) family, the vast majority of which are found only in New Guinea — and I wanted to see them all. If I had deeper pockets, I would have stayed in the country until I'd done exactly that and notched up all 40, but with a seriously small budget, I wondered how I would fare.

My first 'BOP' encounter (other than the ones plastered on beer cans, mugs, T-shirts, billboards and even the national flag) was in the jungles north of Port Moresby. There are no roads in the country that link the north and south coasts, which means that if you want to go overland you have to walk. The infamous Kokoda Trail crosses a formidable assortment of dagger-edged mountains, called The Owen Stanley Range. These peaks render any hopes of a cross-country road impossible. It takes about nine days to walk the trail, and I wouldn't recommend it: it's HARD, but that's another story... Whilst sitting exhausted at camp on day six, watching an assortment of birds visiting a gigantic fruit tree, a male Raggina's Bird of Paradise dropped in. I would like to say at this point that it was the most impressive bird I've ever seen, but it wasn't. It was an immature male and sadly lacking its display plumes, which left me with a slight dissatisfaction — but it was certainly an appetite-whetter for things to come.

Habitat around Kumul Lodge, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea (Photo: Jack Wylson)

My next encounter was several days later. I must mention here that I was travelling with my (non-birding) friend and partner in crime, Adam, which slightly hindered my Paradisaeidae hunting. After a marathon bus ride up into the Highlands of PNG on surely some of the worst roads in the world, we found our way to the magical Kumul Lodge, high in the mountains of Enga (pronounced 'anger') Province. We were the only guests, and were welcomed with big smiles and keen handshakes. Kumul is unusual as an eco-lodge in that it is owned and run by local people, proud of their wildlife, and earning money from it. PNG is not really a budget destination compared to the likes of southeast Asia, particularly when it comes to accommodation, and this was a shoestring adventure on the most minimal of funds. That said, from my desk here in England I can't complain about paying the equivalent of £30 a night for a twin room directly in front of a Crested Bird of Paradise display tree! But at the time it seemed a necessary extravagance.

We dumped our rucksacks in our room, and I examined the display tree, which was no more than two feet from the window. I could clearly see the nail scratches on the bark. Apparently the male Crested BOP only drops in from time to time — I'd have to be lucky.

Brehm's Tiger-parrot, Papua New Guinea (Photo: Phil Barden)

The cloud had descended, and it was approaching dusk; I assumed that I would unfortunately not be able to see any BOPs tonight. I was wrong. At the check-in desk, I filled out various forms whilst asking about the birds. I was told first to go and look at the feeding table. Feeding table? I hadn't even realised there was one. Rest assured, this was to be a bird table like no other, literally a world away from the peanut hangers at Minsmere. I climbed some stairs to a balcony, opposite which was a rickety, wooded structure heaving with moss and epiphytes, and there on the moss carpet 'tabletop' was a scattering of fruit of every description: mango, banana, pineapple, papaya, it was a veritable fruit salad. Oh, did I mention the birds? Brown Sicklebill doesn't sound like a Bird of Paradise, or indeed conjure up the image of a particularly stunning bird, but imagine a jet-black Hoopoe with a pearly white eye, iridescent bluey-purple crown and mantle, and a tail probably three times the length of its body. Even the brown underparts appeared the most delicate and beautiful of buff-browns. It was tucking into a piece of mango, picking up chunks with its magnificent bill, and tossing them dexterously — and again Hoopoe-like — into the air, then catching them in the back of its throat. Beside it was the more enigmatically named Ribbon-tailed Astrapia, and another in a lichen-draped tree behind. These birds have impossibly long tails, indeed I believe they are the longest in proportion to their body of any bird. Picture a (slim) Jackdaw, with a tail over a metre long! It was stunning. Next to catch my eye, a Brehm's Tiger Parrot, cryptically camouflaged and sitting quietly munching an orange. Belford's and Common Smokey Honeyeaters were everywhere, the latter having the ability to blush, flushing the yellow bare skin on their faces red in a matter of seconds. An Island Thrush and a White-winged Robin hopped about below the table. Slowly the high mountain mist drew in and darkness engulfed the spectacle.

I spent the evening chatting with John and Max, the local guides — very fine folks. Both lived in the villages below the lodge and had learned all the English bird names purely from the tourists they had taken out. Max, one of the guides, told me how he had worked for several years before he acquired his first and only pair of binoculars, donated by a visitor. He was still wearing them round his neck as he spoke, even though it was 10 pm. They were his livelihood, and obviously his most treasured possession. His field guide (also donated by a kindly soul) was equally valuable to him. I wondered how many people, desperate for work in a country with 60–90% unemployment, could be given a similar career simply with a pair of binoculars and a bird guide. I arranged the next day to leave at 5 am to look for the King of Saxony Bird of Paradise, found on the slopes below the lodge.

Long-tailed Shrike, India (Photo: Jaysukh Parekh Suman)

I was awake half of the night, partly with excitement, partly because I didn't want to miss my alarm. John was waiting for me in the dark outside reception. We tramped through the blackness and, as we went, he recounted a local myth:

"The King of Saxony Bird of Paradise and the Long-tailed Shrike were working together digging the field. In those days, the shrike had glorious long head-plumes, and the King of Saxony BOP advised the shrike to take off the plumes so as not to get them dirty. The shrike reluctantly agreed, and when he wasn't looking the King of Saxony BOP stole the feathers for himself and ran away. Although gaining the beautiful head-plumes, he was exiled to the high mountain slopes where he remains today in hiding, while the shrike still tends the fields and the roadsides, waiting for the King of Saxony BOP to return. "

It was an endearing story — all the more so to think that many of the people in the valley below probably still believe it.

The light was slowly growing, from a fuzzy grey on the horizon to a bright, but misty, dew-soaked morning. We reached the site and left the track into the deep rainforest. The jungle was alive with sound, and John listened intently for the song of our quarry. There were females nearby making a harsh squawking sound, then John heard a male and started jogging up the precarious path towards it. I followed, by now almost adept at navigating the New Guinean terrain. The song was a curious rattling, tinkling, river-like sound, growing and fading in intensity. The jungle gave it a ventriloquist quality, impossible to gauge the direction, but John quickly found it, perched on the very topmost branch of a dead tree, silhouetted against the morning sky. Even in outline it was unmistakable: the head-plumes were exceptionally long. It was a spectacular sight. A bird whose plumage looks literally as though it was put on upside-down.

I spent the rest of the day exploring around the grounds of the lodge. My constant amazement continued: Crested Berrypeckers, Blue-capped Ifritas, Goldie's Lorikeets, an obliging Stanford's Bowerbird, all in the lodge grounds. In the early evening, as I was watching a Mountain Firetail, one of the lodge staff ran over calling me excitedly. I could only make out the last word that was said: "....bird". By the expression on his face I could see that whatever it was, it had to be good. I ran after him back to the lodge and was beckoned up to the balcony. There, right up against the window, his steaming breath condensing against the glass — a male Crested Bird of Paradise. I was completely dumbstruck. Until then I had never seen such intense colouration on a bird: he was a dazzlingly flame-coloured, the brightest of oranges. He angrily eyed the glass, probably viewing his reflection as competition then suddenly, with a vehement hiss, he flew back into the trees. He had disappeared all too quickly. I ran back towards my bungalow, hoping to find him displaying on his favoured tree. Adam was nonchalantly sitting on our balcony smoking when I burst in. He raised an eyebrow, "Crested Bird was here," he said.

"What?! You're joking?..." I didn't believe him.

"I knew you wouldn't believe me, so I took a picture". He got out his SLR, and there in the middle of the shot was the male Crested Bird of Paradise.... Sometimes it pays to let the birds come to you.

Crested Bird of Paradise (Picture: Jack Wylson)

My excursion the following morning was to be for the Blue Bird of Paradise. Adam, having seen the 'Crested Bird', couldn't be persuaded to get up before breakfast and walk several miles for another. Being just one person, it was unfeasible, not to mention damn expensive, for me to hire the lodge minibus to drive between sites. I had spent the previous evening again thumbing through my guidebook pointing at various species and asking Max and John if I had a chance of seeing them. The other speciality BOP at Kumul is the Lesser Bird of Paradise. Unfortunately, however, this site is not within walking distance. The Blue BOP on the other hand was feasible: it was a mere 15km walk into the valley — we would leave at 4.30am.

The next day I slipped quietly out of the cabin so as not to wake Adam. Max and I walked through the darkness for two hours. Bats flew through our torch beam and a Mountain Owlet Nightjar whistled in the gloom. It began to get light gradually. I was worried that we were going to arrive after dawn, but Max seemed unconcerned.

We passed over a raging stream and I caught a glimpse of something moving in the rapids — a pair of Torrent Larks. Last night, to my disappointment, Max had given me a flat 'no' when I had asked if we had a chance of seeing them. Now the joy on his face mirrored mine: he'd only seen these incredible birds once before, with a research team who'd been looking specifically for them. We were lucky!

After what seemed an age of walking we reached the Blue BOP's territory and began climbing a hill. Max was shaking his head. 'I can't hear them calling' he said, tutting. 'Usually you always hear them by now...' This wasn't good news. I was devastated and we'd hardly even arrived! Three hours' walk for an empty tree would be soul-destroying. I was soon cheered up though. A male Superb Bird of Paradise was perched in full view at the top of a huge tree, his blue-green breast shield proudly erect as he sang out over the valley.

Max had earlier described the Blue BOP's song to me: a cat-like, down-slurred 'Kwaa... Kwaa... Kwaa...' Suddenly, quite dream-like, and drifting distantly on the still air, Max's impression materialised. Quick as a flash he sprinted up the near-vertical path at a speed I wouldn't have thought him capable of. I followed as best I could. The cat-like call grew closer. Max obviously knew exactly which tree the bird would be in. Suddenly he stopped up ahead and motioned for me to approach slowly, quietly. I did so, still breathing hard, having just climbed a few hundred feet in not much time at all. Below us was a big dead tree, and on top of it, in full view — a male Blue Bird of Paradise. I've seen a few species in my life, about 1000 I think, but this was without doubt the most exquisitely beautiful of them all. Surprisingly the most immediately striking feature was not the dazzlingly bright electric-blue, but its ivory-white bill, matching its thick white eye-rings, giving the impression of beautiful, elegant eyelashes. The black of the head and mantle contrasted markedly with the blue of the wings, which was an incredible, aquamarine-turquoise. The tail came in two distinct parts: fluffy, lace-like flank plumes, from which extended two long, delicate filaments with small spatula-shaped ends. It really was one of the most glorious birds I have ever been fortunate enough to see.

Blue Bird of Paradise (Picture: Jack Wylson)

We watched this stunning BOP for some time. Unfortunately I was surrounded by a swarm of quite probably malarial mosquitoes and my repellent had long lost its effectiveness; eventually they drove us back down the hill. In my excitement I had barely noticed the almost constant stream of villagers passing us on the path. They were all heading in the same direction, and, now that we were heading back, we were going against the flow. I asked Max why there were so many people here. He explained: a young man in one of the villages above us had died last night from HIV. People were coming from all the surrounding villages for the funeral. Despite the sombre occasion everyone I passed gave me a warm smile and insisted on shaking my hand. The number of people was swelling, and as we passed downhill we reached a bottleneck in the path with only enough room for single file. We waited as the tide of locals passed; I duly shook hands with each. The more people I shook hands with, the more plucked up the courage to approach me. I felt like royalty. When we finally reached the road I had probably greeted and shaken hands with at least 200 people. I suppose that justly summarises the hospitality and humility of the people of PNG, certainly amongst the kindest I have ever met.

In Part II Jack Wylson crosses into Indonesian West Papua and goes in search of the aptly named Wilson’s Bird of Paradise.