Ancient Egyptian society has long been a source of fascination for historians, with the practice of mummification viewed as one of its defining customs.

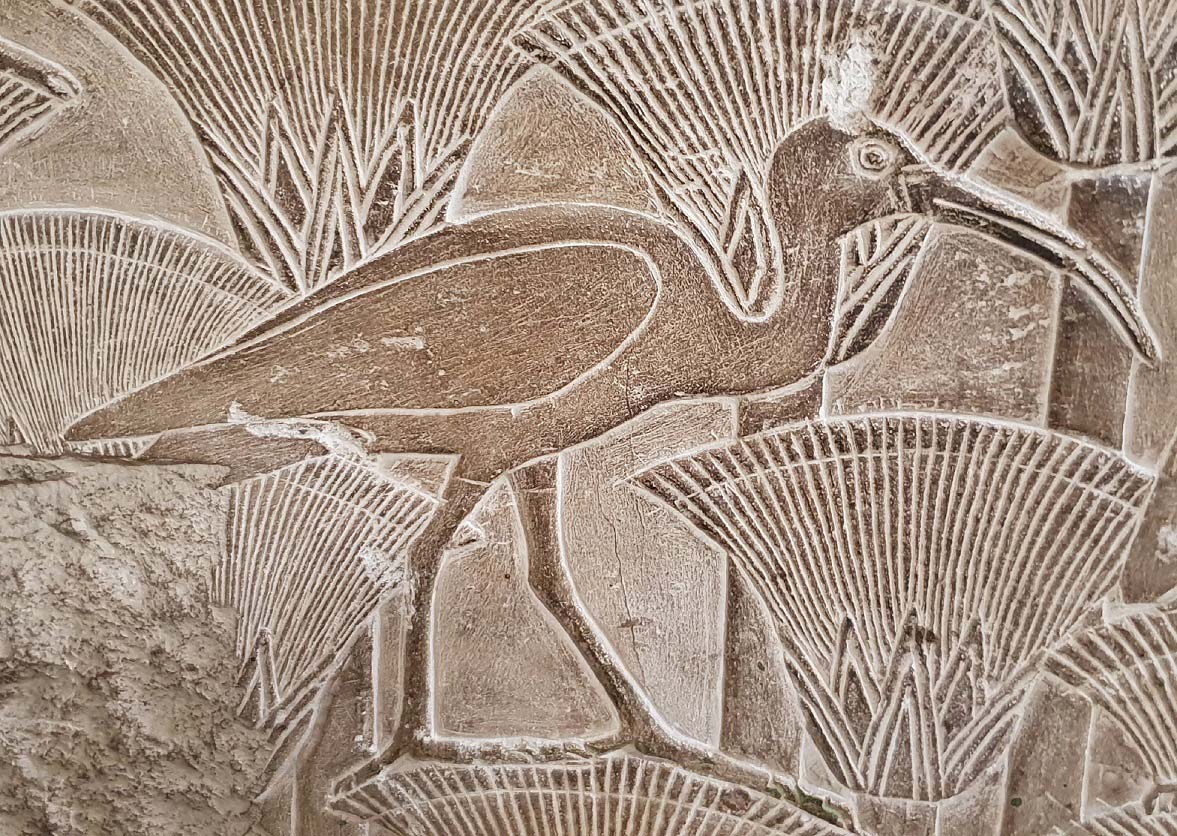

But as well as human bodies being preserved, Ancient Egyptians were also well-known for mummifying animals. Over a period of hundreds of years from around 600 BC, millions of African Sacred Ibis were sacrificed to Thoth, god of magic and wisdom. The birds were offered to Thoth, which had the body of a human but the head and bill of an ibis, in the belief that it would cure illnesses or gift long life.

About 15,000 birds were estimated to be mummified and offered annually at each temple site, of which there were many throughout Egypt. The ibises were mummified and placed in clay jars by temple priests. The mummies were stacked floor-to-ceiling in many rooms within the catacomb sites. This happened on a staggering scale, with more than 1.5 million mummified ibises were deposited at Saqqara and some 4 million at Tuna el-Gebel.

African Sacred Ibis were sacrificed in their millions in Ancient Egypt (Griffith University).

Given the industrial scale of the slaughter, many Egyptologists have long considered it likely that the species was actively farmed to ensure that enough ibises were available to keep up with sacrificial demands. However, a 2019 study published in the journal PLOS ONE suggests that most ibises were in fact captured in the wild and then kept in captivity for a time before being sacrificed.

The study examined the DNA of 40 African Sacred Ibis, with 26 of these being modern samples and 14 being from mummified birds retrieved from five different ibis burial sites in Egypt. Analysis of the mummified ibises showed a high degree of genetic diversity, similar to that witnessed between modern populations of the species. The researchers argue that if the birds had been bred in large farms, the ibises would have become less genetically diverse over time and more susceptible to common diseases, as is seen in modern industrial bird farms (such as chickens).

Dr Sally Wasef, lead author of the study, explained: "This suggests it is unlikely that African Sacred Ibis were farmed on a mass scale as the genetic consequences of that would have been low genetic diversity owing to the shared DNA between inbreeding family groups over time.

"It seems clear that they did not establish long-term industrial scale farms to have millions of birds to sacrifice each year.

"We suggest that the genetic data indicates that the local people obtained wild ibis yearly, tamed them and raised them for mummification, so it was also beneficial for the community and the economy."

African Sacred Ibis is now extirpated from Egypt (Paolo Caretta).

The notion that the ibises were farmed is "simply a guess to explain the huge numbers" and is "not based on any archaeological or documentary evidence", according to Aidan Dodson, an honorary professor of Egyptology at Bristol University. If they were instead being captured in the wild, it suggests that the species was once common and widespread in Egypt.

African Sacred Ibis is now extirpated from Egypt, with the last birds disappearing in approximately 1850 – many centuries after the practice of sacificing the birds had finished. Researchers have presumed that the species disappeared as the country's climate became drier over time, but other factors are also likely at play.

Reference

Wasef, S, Subramanian, S, & 10 others. 2019. Mitogenomic diversity in Sacred Ibis Mummies sheds light on early Egyptian practices. PLOS ONE. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223964