As aspiring rare bird finders, the appearance of vagrants and their intimate relationship with weather is something that has both fascinated and frustrated us in equal measure.

There are some weather events that we know will invariably produce birds. On the south coast, light winds and poor visibility in late April can produce a fantastic arrival of migrants. In late September on Fair Isle, a south-easterly airflow off a continental high can result in spectacular falls of scarce and rare birds.

Predicting arrivals from the Near Continent and further east is well understood and involves a reasonably high level of accuracy, but what of trying to pre-empt arrivals of passerines from North America?

There is a theory we can follow, as outlined by Norman Elkins in his 1983 book Weather and Bird Behaviour, and again in 2009 by Alex Lees and James Gilroy in Vagrancy Mechanisms in Passerines and Near-Passerines. It's not my intention present this reasoning as if it were my own, rather more to use this article to illustrate the idea with some historical examples with a view to birders being able to predict future falls of Nearctic landbirds.

This American Yellow Warbler was found at Portland Bill, Dorset, on 21 August 2017. It may have come a long way, but looking at the synoptic charts preceding its arrival, the occurrence of this and other American landbirds in south-west England and Ireland was 'predictable' (Tim White).

In contrast to the birds reaching our shores from the east, Nearctic vagrants will have journeyed across at least 3,000 km – and possibly as far as 5,000 km – of open ocean in one unbroken flight. There appear to be more nuances and less reliability involved when trying to predict their arrival.

Unlike waders and wildfowl, the autumn appearance of smaller passerines seems to be intrinsically linked to fast-moving weather systems originating from the eastern seaboard of North America, anywhere from Florida to Newfoundland. Sea temperatures in the mid-Atlantic fluctuate year on year, which in turn dictates how many weather systems moving west off the coast of West Africa go on to develop into tropical storms and hurricanes. As they approach the Americas, these systems deepen and gain strength over warm oceanic water. They either make landfall or pass just offshore, then track north-north-east and spinning out into the Atlantic, towards north-west Europe.

Such systems can be hugely destructive and powerful but trailing off the intense centres are less turbulent weather fronts. The warm fronts are reputedly the most hospitable sectors of the storms and it is in these areas where we believe small birds can make the long sea crossing and survive. Although the weather systems are large, it is where the warm fronts make landfall that can give one an idea where the birds may be deposited – in some instances producing small falls of American vagrants in a relatively small area.

This in turn gives credence to the theory these are indeed 'bird-friendly' sectors of the storm systems. In some cases such weather systems can cross the Atlantic in 36 hours or less. The oceanic crossing allows for no rest so speed is a critical factor as to whether birds caught up in such systems survive the journey. The exhausted or even moribund state that Black-billed and Yellow-billed Cuckoos often arrive in demonstrates that such journeys, even the fast ones, are right on the limits of capability for some species.

Being able to anticipate the arrival of American landbirds gives any bird finder a real head-start. The Yellow-bellied Flycatcher on Tiree in September 2020 appeared following a small but fast-moving system that caused a 'direct hit' in western Scotland (Jaz Hughes).

In some autumns the Azores High can be a troublesome influence in the progression of these storms. When it is a dominant feature in the North Atlantic, this large area of high pressure can block, slow, even stall the progression of eastbound low-pressure systems, or deflect them to the north towards Iceland. It's when this high pressure is weak, sitting further to the south, in unison with an active hurricane season that it really 'opens up' the North Atlantic to swift-moving weather and consequent transit of North American landbirds to Europe.

Of course these weather systems have to interact with and disrupt actively migrating North American birds – a subject worthy of a more in-depth reading. Many of the most frequent vagrants, such as Red-eyed Vireo, Grey-cheeked Thrush and Blackpoll Warbler, have migration strategies that take them out over the Atlantic towards South America, predisposing them to frequent interaction with such weather. Other, less common vagrants, such as Chimney Swift, seem to require a more complicated set of circumstances that involves something called 'retro-grade migration' where, in late autumn, birds move back into North America in a seemingly counter-intuitive movement that then makes them vulnerable to encountering these eastbound storms heading for Europe. I saw such 'retro-grade' late autumn movements while living in Cape May, New Jersey, where the appearance of many Cave Swallows took place in November 1999.

This Cedar Waxwing arrived on St Agnes, Scilly, in early October 2017, following the 'perfect storm' for transatlantic vagrancy. More on this particular system can be read in the examples below (Simon Knight).

To conclude, this mechanism of transit won't explain the appearance of every single vagrant North American landbird each autumn, but it certainly is present where multiple arrivals occur. What follows are examples of weather charts, which illustrate the theory and the birds they produced.

Before looking at the examples of charts that follow, it may be of use for some readers to refresh their memories on how to read weather charts. The video below, produced by the Met Office, provides a helpful reminder.

Examples of reading synoptic charts

1 November 2005

This chart shows an approaching system which appeared to help turbo-charge an influx of Chimney Swift into Britain and Ireland, with dozens of birds having already made it to the Azores in the final days of October. In this chart, as well as those that follow, the relevant warm front is marked in red.

23-24 August 2008

A remarkable fall of American landbirds took place in Ireland in late August 2008. These charts show weather for 23rd (top) and 24th. Two American Yellow Warblers were found on 26th (on Cape Clear and at Mizen Head), with Cape Clear also producing Northern Waterthrush and Solitary Sandpiper on 27th.

20-21 August 2017

Who could forget the memorable and simultaneous appearances of American Yellow Warblers in Co Cork and Dorset in August 2017? Again the approaching warm fronts are clearly visible on these charts from 20th (top) and 21st, even seeming to sweep up into the channel towards Portland! Both birds were found on 21st.

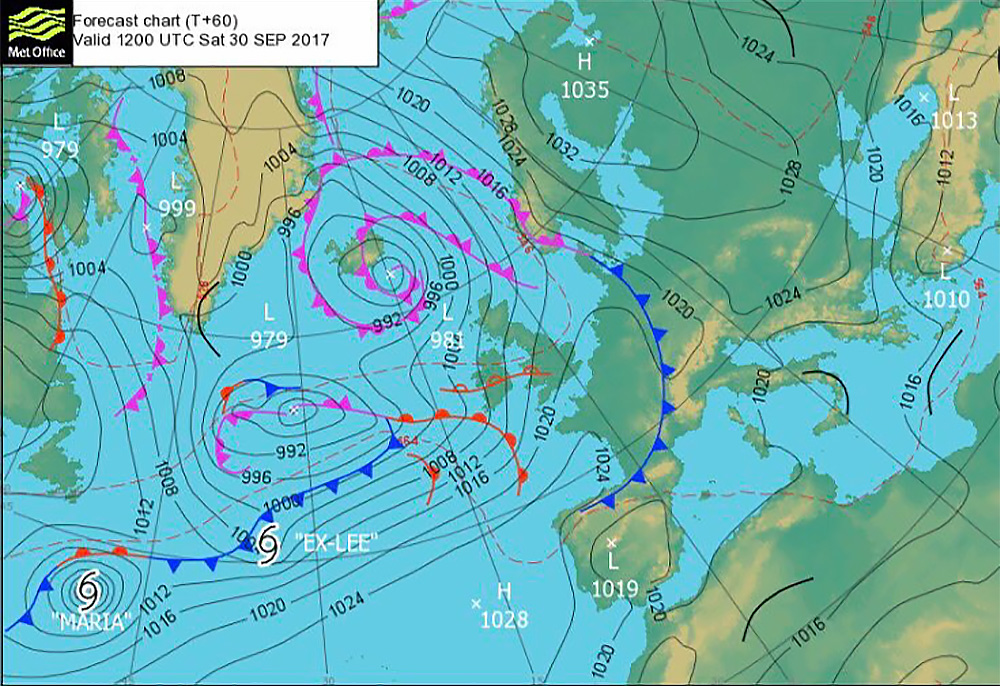

30 September 2017

A chart from late September 2017; one that I like to return to as one of the most mouth-watering forecasts an aspiring North American rarity hunter could wish for. An approaching warm front backed by multiple fast-moving ex-hurricanes created a perfect storm for vagrant birds from the west. I remember being on Scilly, thinking the forecast was "too big to fail" at the time – and so it proved. Cedar Waxwing, American Cliff Swallow and Red-eyed Vireo were found in the isles, joining a Rose-breasted Grosbeak already discovered a few days previous.

12 September 2020

Here we have the charts prior to the discovery of the Yellow-bellied Flycatcher on Tiree, Argyll, on 15 September 2020. This is an example of a very small but very effective warm front passing through the Hebrides. I stuck my neck out at the time, predicting something based off the chart – as it turned out, it was a pleasing example of being able to pre-empt arrivals from across the Atlantic!

References

Elkins, N. 1983. Weather and Bird Behaviour. Bloomsbury, London.

Lees, A & Gilroy, J. 2009. Vagrancy mechanisms in passerines and near-passerines. Rare Birds, Where and When: An Analysis of Status and Distribution in Britain and Ireland.