One evening three years ago, we found ourselves reminiscing with friends in Cley on how, as young birdwatchers in the 1960s, we were enticed across the Irish Sea to Cape Clear Island in search of rare birds and had then been charmed by the scenery, the sea, the people and the pace of island life. We shared our collective memories; the experience of sitting on the rocks of the extreme southwest tip of Ireland watching gale-driven Great and Cory's Shearwaters passing close by. We discussed the thrill of finding bird species that had not previously been recorded in Ireland and what it was that had then persuaded Stephanie and me to exchange our secure jobs to spend a year running a remote Irish bird observatory. The challenge was laid down, and next day we dug out the old 35mm slides, dusted off the diaries and went through faded letters and then decided to write up the whole experience for others to share. It has been the memories of some larger-than-life people, the unexpected events on the island, and the stories of Observatory life, that have provided a much broader context for the bird records than simply describing the island. It has been a lot of fun, particularly as over one hundred characters emerged to be included within the narrative!

Seawatch at Pointabullaun Cape Clear 1964 Left to right: Observatory visitors, Tom Green — later to become the first all-year Warden at the Observatory; Geoff Oliver — now resident island ornithologist; Paul Barbier — legendary Observatory pioneer with 236 days of visits from the UK in the 1960s; and Geoff Bromfield (photo: Tom Green)

Situated at the southwesternmost point of County Cork in Ireland, Cape Clear Island is ideally placed for watching the great Atlantic movements of seabirds, to sample migration and to receive American vagrants. Although only three miles long and never more than a mile wide, there is a wide variety of landscape with both cultivated and bracken-infested fields, a lake, bogs, open heather-covered moorland and recently planted areas of pine trees. It is a challenging island to 'work' but for 50 years it has captured the imagination of generations of birdwatchers and added around 30 new species to the Irish (or occasionally, 'British') list!

During term-time in my teens, my birdwatching friends and I would eagerly anticipate the weekly Oxford Ornithological Society (OOS) meetings to exchange information on local bird sightings. With no telephone system of rarity news, we hoped that if there was anything interesting reported it would still be around by the weekend or the next cancelled rugby or hockey match, whichever came first. Our local knowledge grew from putting in the miles, by bike, and reference to the annual county reports, which served as pointers to what might be seen and where. It was very much an era of DIY birdwatching.

In 1960 I went to an evening meeting of the OOS. A short paper read by a young student, Humphrey Dobinson, told of an exploratory birdwatching trip to Cape Clear Island the previous year. He recounted what sounded seemingly unbelievable stories about the sighting of 'large' shearwaters and a number of Hippolais warblers. Suitably impressed and inquisitive, my two friends and I, aged sixteen, immediately set about planning our own autumn trip to the island to help play a small part in filling the gap and mapping the almost blank canvas of western Irish bird migration records.

At that time the rented Observatory house on the island provided little more than indoor camping, and not much improvement on what Humphrey and his friends had experienced in 1959. At that time they simply rolled out their sleeping bags on the bare boards. At least we had the camp beds. We shared the cooking (heating up tins ofr beef and veg', or doing eggs) on a paraffin Primus stove. We fetched buckets of water from the well for washing or drinking. There was one paraffin lamp providing necessary light for writing up the logs, but otherwise we used candles, or more likely went to bed early, ready for dawn seawatches with a main course of daily Bonxies and Sooty Shearwaters, which were a real eye-opener to land-locked English observers! Each day was eagerly awaited and often brought rewards for the long days watching.

In my notes for 3rd September 1961 I recorded:

'Apart from the ever-present Wrens and small family groups of fussing Stonechats there was little about. From the narrow track between the Glen and the Lighthouse Road I could see what I thought was a Chiffchaff or Willow Warbler. It was flitting through the thinly leafed branches of a small Sycamore tree hunting for insects. On closer inspection I could see that this dainty Phylloscopus warbler had almost white underparts, a greenish rump and green edging to its wing feathers. I knew we were onto something very interesting but could not 'place it' from the memory of the few identification guides I had looked at. We hurriedly wrote notes and went in search of the others. We eventually caught up with them. Fortunately the bird stayed in the same garden for some time and the eight of us later accumulated a comprehensive set of notes. Next day we managed to catch the bird in a mist-net. I had found what turned out to be Ireland's first recorded Bonelli's Warbler'.

I was amazed and as far as Cape was concerned, I was hooked!

Later, as the number of local observers in Ireland increased above a mere handful, a strong Anglo–Irish birdwatching partnership was born. Of particular importance at that time was the involvement of young Cork watchers such as Clive Hutchinson, Ken Preston, Mike Hartnett and Tadhg O'Keefe. We all felt very much part of this exciting venture. We learnt a lot from each other. This partnership worked well with the UK providing the tradition of research and record keeping and Ireland providing local knowledge and boundless enthusiasm.

Gannet, Cape Clear, Cork (Photo: Tom Green)

The Observatory Council was keen to get all-year-round observations on the island before the end of the first ten years of the Observatory's work. After two years of teaching I rashly suggested to Stephanie that a 'gap year' on the island might be an exciting idea before settling down to a more conventional life back in the UK. This is what we did in 1968/69. With ringing, surveys, the first courses for students and mid-winter seawatches, we set ourselves what was to prove to be a tough agenda. It was exciting, but the novelty wore off in the bleakness of winter and several periods of heavy snow during one of the worst winters in living memory, in a house with no electricity and a six-week-old baby to look after.

The hundreds of acres of bracken and gorse and the many small stone-walled gardens all provided dense cover in which small birds hid. This was more of a field observation challenge than a ringing station would be. It was also the era of relatively limited optics. However, for the price of a large 'jubilee clip' and a small camera tripod I managed to stabilise my 12x50 Bar and Stroud monocular to make it effective for seawatching. This was also a time when few observers had easy access to books with decent illustrations of some of the rarities encountered. In most cases photographs to support field identification only became a reality if a bird was caught and could be closely examined anyway. Such difficulties added to the challenge, but there were still some very special occasions that year including an American Redstart, another Cape Clear first record for Ireland and indeed only the second time one had been seen in Europe. We would have been quite happy with the good fortune of that one sighting, but the next morning soon after dawn I was sitting overlooking the Waist when I noticed a tiny thrush on a wall. I almost jumped, as I watched what, for all the world, was a Robin-sized Song Thrush. It flew down onto the grass nearby where it began hunting for food. The blotchy breast markings were clearly visible. I signalled to the others who were not far away. Together we were able to build up sufficient notes so that after consulting an American field guide, we were able to rule out Grey-cheeked Thrush. We identified this little Catharus thrush as an Olive-backed Thrush. The species was later to be re-named Swainson's Thrush Catharus ustulatus swainsonii. This was the first live specimen to be seen in Ireland.

50 years after its humble beginnings, the Observatory continues to thrive and welcomes visitors to its modernised accommodation on the edge of arguably one of the best small harbours in western Ireland. Few visitors to Cape Clear remain unmoved by the scenery and the welcome they receive from the small island population. It is also a place to sample fantastic seawatching, with the possibility of whales and also very rare landbirds.

Outside the Observatory at Cape Clear A great place for watching Black Guillemots and Chough or simply to sit listening to the rhythmic breathing of the water in the caves! (Photo: Tom Green)

Wherever they are, birds may hold our collective interest, but 'patch watchers' know that it is the context that often holds the magic.

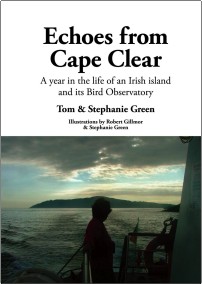

Echoes from Cape Clear by Tom and Stephanie Green is published by Wren publishing.

178 pages. Illustrations by Robert Gillmor and Stephanie Green.

ISBN 978-0-9542545-4-4 Softback. RRP £20

Direct Sales enquiries to mail@echoesfromcapeclear or visit www.echoesfromcapeclear.com.