I was originally intending to follow up my earlier theme on 'The Things We Do For Birds' by describing some more odd employment situations I've found myself in whilst following my lifetime's passion for birds and good birding, but events on St. Agnes in late spring led instead to 'As Good As It Gets' and a change in the flow. I've now decided, therefore, to skip past Part Two and head straight into Part Three — an old-schooler's misty recollections of hitch-hiking the length and breadth of the UK in pursuit of rare birds. Now, sadly, you won't get to read about six months' cheese-making in a kibbutz on the Israel/Gaza border or window-cleaning in Cape May, selling photographs on a pier in southern Ireland or nine months' sheep-farming in northeastern Cornwall! Maybe some other time?

I wonder, now that hitch-hiking has become such a thing of the past, whether any young birders in Britain would ever contemplate standing by the side of the motorway with their thumb sticking out? Do we live in such a different world from the 70s and 80s that to be caught standing at Exeter Service Station at 3 o'clock on a February morning with a sign saying 'Penzance please' is to risk being carried off to a mental institution — or, worse, to risk being stood there forever with everyone driving past you and ignoring you or wondering what on Earth it is that you're doing?

If the concept of hitch-hiking is foreign to the majority of modern-day birders, then I promise you that everything that is recorded in the following pages really did happen 20 and 30 years ago. Of course not everyone hitch-hiked to birds back then — like now, most twitchers had cars of their own and formed regular teams — but for some of us, university students like myself with a hardcore obsession for birds but no cash to back it up with, hitching was the norm. The fact I failed my driving test three times (and completely gave up trying as a result) meant my hitching 'career' has extended for much longer than many of my contemporaries. (I made a go of it a couple of times on my return to the UK last year — hitching, that is, not driving — and found that really not that much had changed: waiting time still averaged about one hour.)

Remember, as you read these extracts, that I was only one of several dozen young twitchers who used to hitch-hike to rare birds up and down the country during the mid–1980s. Others would have started before me, back in the 70s, and some may have equally harrowing stories to tell. In particular, for anybody who is in the least bit entertained by the stories below, I thoroughly recommend finding yourself a copy of Kenn Kaufmann's Kingbird Highway — a 1970s look at a young birder hitching his way to a record American Year List. Some of the distances he covered, and some of the things he did in pursuit of birds (living on cat food for a year!), make what I am about to say seem piffling by comparison. But anyhow, here goes...

I had a few hundred quid saved up from part-time jobs when I was about 16 or 17, but that only lasted me for about nine months twitching in team and then I was on my own. My first big hitch, when I was a 17-year-old schoolboy in the middle of A-levels, was for the Sussex Little Crake of March 1985, a small matter of about 360 miles from my home. I can still remember the tension and torment as I sat in my local library for two solid days studying a road atlas of Great Britain and the route between me and this bird at Cuckmere Haven, West Sussex. Eventually I decided on the most straightforward (but with hindsight, not the most sensible) route south from Newcastle: A1 straight into London, A2 south towards Brighton.

Leaving my folks' home at nine on the Friday evening, I first had to hitch 10 miles north in the wrong direction to get to the start of the A1(M) motorway, at the junction known as White Mare Pool, with which I was to become inordinately familiar over the course of the next five or six years. My first proper lift, after an hour or so of waiting, was with a kindly lorry driver who took me 120 miles to the Wetherby junction in Yorkshire, telling me that he drove the exact same route every Friday night, and that he would look out for me if ever I was standing in the same place at the same time. (I never saw him again!) What I remember particularly about that night was that the third lift I got was with a French lorry driver who asked me early in the piece whether I would like to go to bed with him (I declined politely); and that at 4 o'clock in the morning, having followed the A1 all the way to the intersection with the A2, I found myself standing at a set of traffic lights in Brixton, in the very centre of London, a little white boy all on his own not long after the famous race riots of the Thatcher era. I'm sure it was only sheer naïve recklessness that saw me through what in more 'enlightened times' I might have looked on as a very unsafe position.

Little Crake, Exminster Marshes RSPB, Devon (Photo: Dave Perrett)

Miraculously I arrived safely at Cuckmere Haven at much the same time as the 300-strong crowd who had travelled from all over the country to pay their respects to this most welcome bird, the first twitchable occurrence in Britain for many years. Some friends of mine took pity on me and squeezed me into their already overloaded car (there were four of us crammed in on the back seat) and transported me back at least as far as Lincolnshire, where I asked to be dropped off to go and look for another bird I 'needed' — two Red-breasted Geese had been seen on the marshes at Wrangle Flats for the past couple of weeks. Dressed in little more than a T-shirt and a light jacket, I spent the night in a telephone box, shivering to keep warm. I didn't see the geese next day — but I did get a lift to within 30 miles of my home by some more visiting birders. I lay soaking in the bath that night, elated at the thought of having seen the Little Crake for free and contemplating the new horizons that had now been opened to me after this first little adventure.

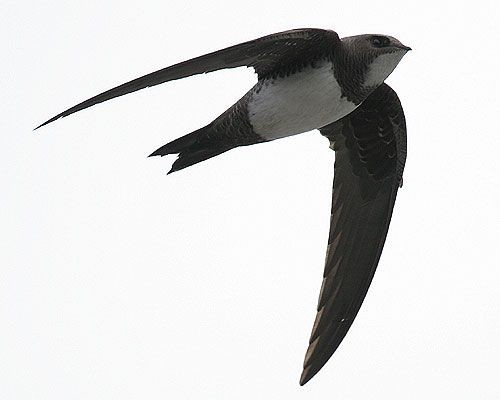

Two weeks later I was off to Kent overnight for a Sociable Plover, and a week after that I managed to get to Norfolk for an Alpine Swift in just two lifts!

Alpine Swift, Barnston, Cheshire (Photo: Ian Butler)

More remarkable still was the ride I got from Leicester Services on the M1 to Newton Abbot in Devon, just four miles from the Ring-billed Gull I'd set off to see from Newcastle earlier that morning, expecting to take at least 24 hours to get there. This was the first journey I'd done from the east of the country to the west and, because you are not allowed to hitch-hike at motorway intersections, it had taken me a long time to decide which was my best possible route.

Ring-billed Gull, Gosport, Hampshire (Photo: Daniel Trim)

In later years I was to use the M62 west from Ferrybridge in South Yorkshire and take my chances with the complex of roads south of Manchester to get me on to the M5, but on this first occasion I had decided to hitch all the way down the M1 into London and then turn off west along the M4. I'd just been dropped off at Leicester Forest after making speedy time down the A1/M1 and was heading out to the exit ramp when a chap stopped and asked where I was heading. "London," I said, somewhat hopefully. "Ah," he said, "that's a shame; I'm going to Devon. Sorry I can't help you." Devon was 220 miles from here, cross-country, along A roads I hadn't even contemplated taking ('stick to the motorways' was the general rule). I managed to change my mind about going to London very quickly and blurted out I was going to Devon too before my driver could move off and leave me standing. That was how I got to be watching my first Ring-billed Gull just eight hours after leaving Newcastle, instead of 24 hours later as I'd first imagined.

Lifts as good as that are quite rare in the hitching world but generally, with a certain degree of common sense, it wasn't all that difficult getting around. Choosing where to stand and the right places to get out — roundabouts and service stations are best, avoid turn-offs and slipways as best you can — will speed you on your way. Inevitably though, you will have your Big Wait — especially if you hitch at night, and especially if you hitch in twos, which I did on my next journey, to a Squacco Heron in north Cornwall, in May 1985.

Squacco Heron, Earith GPs, Cambridgeshire (Photo: Garth Peacock)

Getting there wasn't too bad — although I think it took about three hours to actually get going at the very start — once we'd befriended a Geordie lorry driver who took us from Spaghetti Junction (now there's a spot I wouldn't want to get dropped off again, if I could possibly help it) and dropped us well south on the M5. It was getting back after we'd seen the bird that caused us the problems. Our lorry driver had told us that if we could get back to Birmingham by a certain time next morning, he would be able to take us and drop us all the way home. Things were looking good until we found ourselves waiting four hours at a junction near Bristol. We'd already missed one night's sleep on the way down, and now at two in the morning, we looked like missing another. I think I was actually fast asleep, still standing up, and still with my thumb sticking out at ninety degrees, when we finally got picked up and whisked off to London in a 120mph sports car. There was some lengthy saga that followed about us zigzagging across the motorways from Bristol to London to Birmingham (where our man had left three hours earlier than promised) and finally home to Newcastle about 24 hours later. It involved us getting split up on several occasions, involved my mate Dave leaving his bins behind and having to get out of the truck we were riding in and going back to find them. It involved the truck then breaking down by the side of the road and leaving me stranded — but it's all too long and too painful to tell. Suffice it to say Dave vowed never to hitch-hike again in his life (and I don't think he has) and I decided to give it a miss for the next couple of months.

White-billed Diver, Hayle Estuary, Cornwall (Photo: Steve Seal)

So yes, good times and bad; I can recall another four-hour wait one night, on my own this time, at Birch Services on the M62, but I never came close, I'm pleased to say, to the legend of some poor bloke who got stranded at Hamilton Services, Glasgow, for 24 hours! I managed to hitch to Belfast (from Norwich) one time for a White-billed Diver; hitched to Shetland (or at least to Aberdeen) three times (twice from Newcastle, once from Norwich) and even did the full 1100-mile round trip to Scilly and back from Newcastle. In fact, Alan Lewis and I succeeded in getting the joint-top Year List in the UK in 1986, covering some 35,000 miles apiece, more than half that distance covered by hitch-hiking, sitting in the passenger seat and yakking away to some stranger or other who'd picked us up somewhere in the middle of the night, trying to keep him awake. There were plenty of lifts with long-distance lorry drivers, as you'd expect, but also lots of surprises: I've ridden in Mercedes, BMWs, a Rolls Royce, an off-duty ice-cream van; ridden a hundred-miles on an empty coach all to myself; ridden locked up in the back of a security van with two Alsatian dogs licking my face; gone 200 miles down the A1 in a clapped-out old London Taxi Cab backfiring the entire journey down. I might not have always realized it at the time, but looking back, really, it was mostly a lot of fun.

During the course of our 1986 'Big' Year List, Alan and I did some pretty extreme things. It was one thing to be hitching some 400-odd miles for a relatively 'common' rarity such as Ring-billed Gull — at least it was a lifer — but to year-tick Scarlet Rosefinch? There had been this singing male Rosefinch on the Isle of Skye for a fortnight or so and the two of us had discussed a couple of times whether we were going to bother going all that far out of our way for a bird we'd probably see easily in October. I came home one evening after a quiet seawatch determined to tell Alan that hitching 450 miles for a mere Rosefinch was completely out of the question. My mum was waiting to tell me: "Alan's been on the phone, love. He says he's in Edinburgh on his way to see a Scarlet something or other." I was packed and on my way ten minutes later.

Common Rosefinch, Tyndrum, Forth (Photo: Willie Mcbay)

Well, we saw the bird next day after an eight-hour wait in the rain, and although I did in fact end up seeing a further ten individuals that autumn (including a flock of four together on Fair Isle), it remains to this day the only singing male Rosefinch I've ever seen, so the madness was worth it — though many might disagree!

White-winged Black Tern, Dungeness RSPB, Kent (Photo: Adrian Dowling)

About a month later, I set off on an equally ridiculous hitch — a 700-mile round trip to Dungeness to year-tick a juvenile White-winged Black Tern (I'd seen two summer-plumaged adults previously so, again, this was a 'plumage tick', if you like). Dungeness is the sort of off-the-main-road destination where it takes almost as much time to hitch-hike the last 30 miles as it does to cover the first 300, and this was the case here. Once again though I got there and saw my bird. The thing was, though, a week after that I rode down with some friends for a Bonelli's Warbler in Devon, and we just popped off somewhere on the way back for...another juvenile White-winged Black Tern! If only I could have foreseen the future, I could have saved myself the effort the week before.

Western Bonelli's Warbler, Fair Isle, Shetland (Photo: Deryk Shaw)

One of the nights Alan Lewis and I found ourselves on Skye — a night, as I've hinted, of torrential rain — we found ourselves an old abandoned workman's hut in which to make our beds. This brings me to a related theme in our pursuit of The Things We Do For Birds: some of the ridiculous places in which we have slept! This workman's hut was about five and a half feet long by about five feet wide, and it meant that, at 5'6" and 5'10" respectively, my friend and I had to spend the entire night sleeping with our legs in the air, propped up against the walls of the hut. This discomfiture aside, we thought that at least we'd found a splendid isolated spot in order to catch up on missing our sleep during the hitch up the A9 the previous night. It turned out, however, that we'd somehow placed ourselves immediately adjacent to what may be the only nightclub on the whole of the Isle of Skye, and at 10:30 in the evening, about five minutes after I'd begun to nod off, the most unearthly racket set up right outside our door. As if this wasn't bad enough to keep us awake, at some time after midnight we were disturbed by a drunken young couple who threw open the door and barged into what we thought was our 'secret' hiding place, and were most put out to find that the hut in which they presumably wished to conduct some sort of lovers' tryst was already occupied.

By no means was this an isolated incident in my life on the road. As hardcore hitching twitchers, Alan and I were practically inseparable for about 18 months from October 1985 to January '87. On another occasion we were bedding down for the night at the bus station in Penzance when we were disturbed by a couple of local tramps itching (perhaps quite literally) for their beds. I pretended to be asleep already but Alan ended up engaging them in heated discussion as to who owned squatting rights to the bus station benches. "Oh well," I heard one of the down-and-outs concede. "If you won't let us have our benches you could at least pass us our cardboard blankets that are stuffed down the back." Alan obliged and off they went.

If we had more time to spare and you were actually interested I could list you 50 or 60 holes and hedges that I've crawled into over the years on my way to see some bird or other. (I could tell you about the rabbit that crawled into my sleeping bag one appallingly wet and windy night in a drafty bus shelter somewhere near Sumburgh Head.) The birding gossip that goes around links us all in some ways and last year, on St Agnes, I met for the first time an ex-Norwich birder, John Foster, who had gone on to meet Alan long after I'd returned to the Northeast. After we'd been chatting for some twenty minutes he turned round to me and said: "So, you must be the bloke who slept in the middle of the A1 with Alan Lewis back in the mid-80s!" I could not deny it. In fact, I remember the occasion rather too well. The two of us had hitched back down to Norfolk from our respective homes in Newcastle and Cheshire for a Quail during our summer recess from the University of East Anglia, and at 4 o'clock in the morning on our way for the Nottinghamshire Honey Buzzards, we simply crashed out on the roundabout at the Clumber Park turn-off, completely exhausted, curled up and went to sleep. At that time of the morning the place is crawling with enormous juggernauts, headlights ablaze, noisily changing down gears as they circumnavigate one of the largest traffic circles in the UK. Even now, I sometimes think of that moment when I'm struggling to get to sleep; when one tiny, whining little mosquito is keeping me awake I can barely believe that we were able to crash and go to sleep amidst all that cacophony and grinding, crunching metal. But we did.

Honey Buzzard, Wykeham Forest, North Yorkshire (Photo: Dave Mansell)

My favourite ever — and I'm going to stop here because I could go on for ages — the lowest of the low as far as I'm concerned, was the night I spent underneath a road-sweeper in the car park at Cardiff Services off the M4! It was a Saturday night and Saturday nights are about the worst time to be hitching because nobody is going anywhere for first thing on Sunday morning. Even Sunday nights are better than Saturday nights, with most long distance lorry drivers starting their week at about 4 o'clock on a Sunday afternoon, making ready for deliveries for first thing on a Monday morning. I'd hitched down from Newcastle on the Friday (Good Friday, it was) for a Whiskered Tern at Slapton Ley, Devon, only to find it had gone and flown off that morning and re-located itself a hundred miles away at Radipole Lake, Dorset.

Whiskered Tern, Willington GPs, Derbyshire (Photo: Lee Johnson)

Fortunately there were a number of birders on site who were able to take me the extra 100 miles and we all saw the bird two hours later. Then for some reason I'd decided I wanted to 'collect' a Pied-billed Grebe in South Wales (it wasn't a lifer and I was no longer year-listing) but, again fortunately, there was a friend of mine at Radipole with a car who was heading off to visit relatives in Cardiff, and so at least I got a lift three-quarters of the way. I got to Kenfig Pool, Swansea, in good time to see the grebe that afternoon but it was when I began the long hitch home that I began to encounter some difficulty.

Pied-billed Grebe, United States (Photo: Graeme Stephen)

I found myself standing for two hours in Cardiff, from 10 pm 'til midnight, unable to get a lift. Rain was coming on. For half an hour I examined every possible sleeping location around the Services (including the toilets!) but it had to be acknowledged: the place was practically deserted, and the only vehicle in the car park was, as I say, this council road sweeper.

Notwithstanding the fact that the thing could have taken off in the middle of the night, I was so desperate for sleep and shelter that there, my friends, beneath this contraption, I chose to unfurl my sleeping bag and see what rest I could achieve until morning. Though my face ended up about three inches from the exhaust pipe and I couldn't have turned over if I wanted to, I do believe I succeeded in getting a couple of hours of shut-eye. The bottom half of my sleeping bag was still soaked by the rain when I woke up next morning, however.

Did I ever encounter any dangerous situations whilst thumbing it on the road, or did I ever feel threatened? There were one or two minor incidents that were more odd than dangerous, but I do recall riding some 40 miles along a motorway one night with a bloke who seemed to be in some kind of desperate suicidal state. He was in his late 50s, close to retirement age, and he told me he had been caught fiddling the firm's books and the Board had decided unanimously that the only way to redeem himself was to go home immediately and be caned by his 80-year-old father! Yes, to be thrashed across the bottom with an old-fashioned schoolmaster's stick! The bloke never once turned and looked me in the eye during the 45 minutes of our acquaintance, but his utter embarrassment as he babbled on and on about his dilemma were so tangible I wondered whether he was going to drive us both off the road and to our untimely deaths. He didn't and I'm still here.

The opposite of this instance, a bloke who spent far too much time turning round and staring at me, will certainly go down as the scariest experience I've ever had. In October 1994 I'd just enjoyed a wonderful two weeks on Lundy, and I was in high spirits as I hitched back up towards Liverpool one evening to visit an old Cape May friend, Peter Brash in Runcorn. I'd just got news of two rare birds, a Greater Yellowlegs in Cumbria and a Song Sparrow at Seaforth Docks, turning up the same afternoon, adding to my excitement.

Greater Yellowlegs, United States (Photo: Derek Moore)

As I stood at the last service station on the M6 before heading west along the M62 into Liverpool, remarkably enough, two birders stopped and offered me a lift straight into Cumbria for the Greater Yellowlegs. It was tempting, but Pete was expecting me within the hour and I'd reached a stage in my life where I no longer cancelled previous engagements the minute a rare lifer popped up. I stood and waited a little longer. Soon afterwards, a big blue Volvo pulled up and the window wound down revealing a rather large-looking gentleman sporting a Freddie Mercury-style bristling moustache. When I told him I was heading to Runcorn (about 20 miles away) he said "No problem, hop in." At first nothing seemed untoward, though my driver cut a formidably huge figure in the seat next to me, his head almost touching the roof of the car, and I sat back and relaxed at the thought of seeing Pete very soon. It was certainly nice and warm and comfortable in the car after thirty minutes' wait in the cold and the rain.

Song Sparrow, United States (Photo: Richard Bonser)

Then I began to wonder why we were crawling at 20mph along the hard shoulder of a motorway. I couldn't help notice out the corner of my eye that the bloke seemed to be spending an unusual length of time checking out the wing mirror on the passenger side. I made the mistake of turning round and catching his eye and that's when I realized it wasn't the wing mirror he was checking out, it was me! In that instant I felt more panic than I have ever felt in all of my life. There was no doubting the predatory intentions signalled in that momentary meeting of the eyes. This bloke was, as I say, huge; and I knew immediately that any resistance on my part in the event of an attack would be entirely futile. I sat rigid in my seat, gazing fixedly out the window, feeling very, very small and frightened.

"Ooh, you've got a lovely suntan," said the man with the 'tache. "Been on your holidays?"

"Mmm. America," I mumbled.

Silence. Numb, petrifying silence.

"So, do you do any sports?" he said, his voice sounding like a cross between Paul O'Grady and Danny La Rue. I wondered how much damage I would do to myself if I just opened the door and rolled out onto the side of the road. We had now joined the main lanes of the motorway, but we were still only doing about 40. I thought it best not to risk it. Amazingly — for the bloke kept changing his story as to where he was going and where he had been — he actually dropped me off at the Runcorn junction after twenty of the most nerve-racking minutes of my life. He offered to take me all the way into Runcorn but I lied and told him my friend would be waiting for me here with his car. I slammed the door of the car and ran off down the slipway, diving into the nearest phonebox. I was free, and still breathing. "Pete, Pete," I gasped down the phone, "Oh my God..." I divulged all the gory details.

"Oh him?" Pete said laconically. "Oh he's alright. We all know him around here. He picked me up last month and Paul Derbyshire the month before. He just drives up and down the M62 taking young fellers to where they want to go. When can I expect you? Shall I put the kettle on now?"

I feel now, as I've sensed on several occasions when I've recalled these moments from my dim and dusty past, a strange sense of liberation (as well as a chill up my spine!). It is a release from — and I know I've used this term before and I know I'm going to use it again, but it is such a good one — what Mark Cocker famously called ('that strangest of creatures') my Former Self. Now, from the comfort of my armchair and my 2005 Australian Shiraz, I'm quite fascinated, sociologically speaking, as to what it was that induced young men of my ilk to embark upon these extraordinary quests back in the days when the pursuit of rare birds and a 'list' was the be-all and end-all of my (our) existence. Again I am going to borrow from Cocker. (If you have not read Birders: Tales of a Tribe then you must. Unfortunately his equally brilliant Loneliness and Time: a History of British Travel-writing in the Twentieth Century is probably out-of-print and hard to get hold of now.) You can apply the layman psychologist's 'absent father' syndrome if you like: it applies in my situation, and it is apparent in Alan Lewis's case to a degree — once a source of heated argument between us on that very same morning we tramped the 8 miles from the A1 roundabout to the Clumber Park Honey Buzzards — but a more sophisticated reading of the matter, dealt with by Cocker in Loneliness and Time, is that we hitch-hiking birders of the 70s and 80s were on some sort of a spiritual quest. Maybe it still applies now, I don't know, I can only speak from my own experience. Put it all together — the stringent asceticism in search of some distant, nebulous 'goal' somewhat at odds with the societal norm (to see more birds, to become a 'better birder'?), the rigorous discipline, the apparent indifference to material comfort, the 'otherwordly' consciousness at times encountered — Cocker links all this to the lives of the monks of earlier epochs.

Of course I'm going to agree with him: I know exactly what he means. In fact, on an occasion that a girlfriend convinced me to go and see a tarot card reader, she said much the same thing (the card reader, not the girlfriend): that my astrological chart bore signs of one actively engaged in a 'spiritual search' and that my birding quest had been my personal path to 'individuation' (whatever that may be!). Indeed a more down-to-earth friend, with an interest in such matters and with no interest in birds whatsoever, had independently pointed out much the same thing at round about the same time.

From my own readings at the time (we're talking with hindsight, ten years after my British 'listing' and hitching came to an end) into the Native Indian cultures of North America, I more or less came to the same conclusion myself. I thought I could identify an historical kinship between the Vision Quests of the early Native Americans and the life I lived on the road in Britain from 1985 to 1990: one of deprivation and surrender to Fate. Neither family nor local community, neither University nor career, could offer me the education and identity I found, perhaps somewhat obliquely, through my pursuit of birds and birding. Even now, as I bend my back each day to collect strawberries or gather up bulbs on the Isles of Scilly (activities that would have been part of The Things We Do For Birds: Part Two, if I'd got round to writing it) are gladly undertaken because I know I am here to watch birds. From the Song Thrush that comes into my garden to take currants out of my hand, to the Swallows that nest in my barn; from the Blackpoll Warbler that strays from Canada to the Pallas's Warblers from Russia: these are my raison d'etre, my Spirit Guides, if you choose to use such language, and I occasionally do. Birds provide me with my 'religious connection' to the world and though I've gone some way to explaining (at least to myself) the reasons why I choose to centre my life around the pursuit of birds, often to the exclusion of all else, there is still something inherently mysterious at work each time I pick up my binoculars and find myself focused in contemplation on some feathered creature or other that has happened to cross my path, and I am happier for that.

Let me take this opportunity to thank everyone who has ever given me a lift anywhere — especially the fat bloke with the moustache who dropped me in Runcorn that night. If by any remote chance the World's Most Boring Lorry Driver, who picked me up and drove me up the A1 from Peterborough to Sheffield one night in 1987, is reading this, can I ask him "Why, after numbing my senses with your pointless ramblings for two and a half hours, did you finally tell me thirty seconds before I was about to get out of your cab: 'Ah'm psychic, tha' knows'?" If only you'd mentioned this earlier, we could have had a much more interesting conversation together.