Robert Allen Fitzwilliam Gillmor

Died 8 May 2022

Robert Gillmor in the field (Jody Lawrence).

I would happily bet a reasonable sum of money that most BirdGuides and Birdwatch readers have a piece of Robert Gillmor artwork that they could lay their hands on within a few seconds of reading this obituary. Maybe it would be an original painting or print, but more likely a book, calendar, greetings card, bird stamp or even a soft cushion. Not only was Robert Gillmor our best-known bird artist, but he was incredibly prolific. Many readers will have met him at Birdfair, or BTO or RSPB conferences. Very sadly Robert died earlier this month, but his art will live on – and well beyond our own lifetimes.

Robert was born in Reading and influenced by the Quaker values of his schools. Throughout his life he worked hard and lived relatively simply, willingly helping others when he could. Art was already in his family as his grandfather was Allen William Seaby, an established bird artist who had illustrated Kirkman and Jourdain's four-volume work, The British Bird Book. He also went on to illustrate two early Ladybird books titled British Birds and their Nests. As Professor of Fine Art at Reading University, Seaby was quick to encourage Robert to take an interest in art, showing him prints by various bird artists including Europeans such as Bruno Liljefors and Robert Hainard.

Like all birders born at that time, Robert's first bird book was The Observer's Book of Birds, with its illustrations from the 1800s by Archibald Thorburn and Johannes Gerardus Keulemans. However, his main aim at that time was to obtain a copy of Our Bird Book by Sidney Rogerson. This was illustrated by Charles Tunnicliffe, and more than any other artist's work, these clear paintings inspired Robert. In fact, he went on to help publish three books on Tunnicliffe's art in the 1980s and 1990s. He also built up a complete collection of books illustrated by Tunnicliffe.

Another big influence on his early life were his teachers at Leighton Park School, in Reading. He suffered from poor health at that time which caused him to miss lessons, but rather than waste time he often watched his grandfather paint using oils. Despite his grandfather's influence, however, Robert never saw the appeal of oil painting.

At the age of 13, Robert was the first-ever junior member of Reading Ornithological Club, an organisation that he became intimately involved with, ultimately becoming its life president until his death. He also joined his school's ornithological group, becoming its secretary and then chairman when he was in sixth form. Early birding trips included a group visit to Skokholm, off the coast of Pembrokeshire, where he did a lot of sketching, including of Puffins flying around the cliffs.

Robert's first appearance in the media was at the age of 16 in British Birds, where he provided a line drawing of a several shearwater species in flight for a paper by Max Nicholson.

Robert's first published work, which appeared in a shearwater paper in British Birds in 1952.

After leaving school, Robert studied at Reading University, obtaining a national diploma in art design and a teaching diploma the following year. This enabled him to become a teacher – and where better than back at Leighton Park School, where he became Head of Art and Craft.

Like many artists, Robert was also influenced by the work of Eric Ennion, who was 35 years his senior. In 1960, they jointly organised an exhibition of bird paintings at Reading Art Gallery, which then toured several other venues and attracted great interest from the public. Realising the opportunities to reach new markets they co-founded the Society of Wildlife Artists, which to this day remains the largest influence on wildlife art in the UK.

Nearing his thirties, Robert felt confident to become a full-time wildlife artist. His work was appearing in books and magazines, and in 1970 the RSPB invited him to design its new logo. The organisation wanted a black-and-white emblem, and Avocet was chosen. So popular was the result that he went on to design the logos of the BTO and BOU.

In 1974 Robert married Susan Norman, who was also an established artist. The Gillmor style was becoming well known and demand for his line drawings for the latest bird books was keeping him very busy. It was therefore no surprise that Robert was invited to become the Art Editor for the nine-volume Handbook of the Birds of the Western Palearctic between 1977 and 1994.

Robert Gillmor at work in 1973 (Jeffery Taylor ARPS).

In 1985 Robert was invited to become jacket illustrator for the prestigious Collins New Naturalist book series. He produced more than 70 dustjackets until 2021, when ill health forced him to step back. Not one to be beaten by illness, Robert worked on the last couple from his hospital bed or while convalescing at home. The jackets were as distinctive as those of his distinguished predecessors, Clifford and Rosemary Ellis. However, Robert was rather clever in arranging cameo appearances for some of his favourite places in Norfolk, where he moved with Susan in 1998.

Another dimension to his art career arrived in 2011 when he was invited to illustrate four sets of Royal Mail stamps to show birds of Britain. There were 36 stamps to create, and the popularity of his work resulted in him also doing 18 stamps of farm animals and four of other wildlife, entitled Winter Fur and Feathers.

Red-spotted Bluethroat, Blakeney Point, North Norfolk – a linocut by Robert Gillmor (2005). This was used as the dustjacket illustration for The Birds of Blakeney Point.

Not many birders receive recognition for their work, but in 2015 Robert was awarded an MBE by Prince Charles for his services to art and conservation. He also served on the councils of the RSPB, BTO and BOU – all of which recognized his service by awarding him their most prestigious medals. On receiving the RSPB medal in 2001, he returned to his seat and opened the box to look inside, modestly remembering that it was in fact he who had designed it many years before!

In 2018 Robert became unwell and spent several periods in hospital, often shuttling between his local hospital in Kelling and the larger one in Norwich. During one very urgent transfer in the middle of the night the paramedics thought Robert had died. Just at this point the ambulance hit a large rut and everything and everyone bounced into the air. With the jolt, Robert came back to life! He told the story to his friends later – as always playing down the significance. Typical of his humble and generous approach to life's challenges.

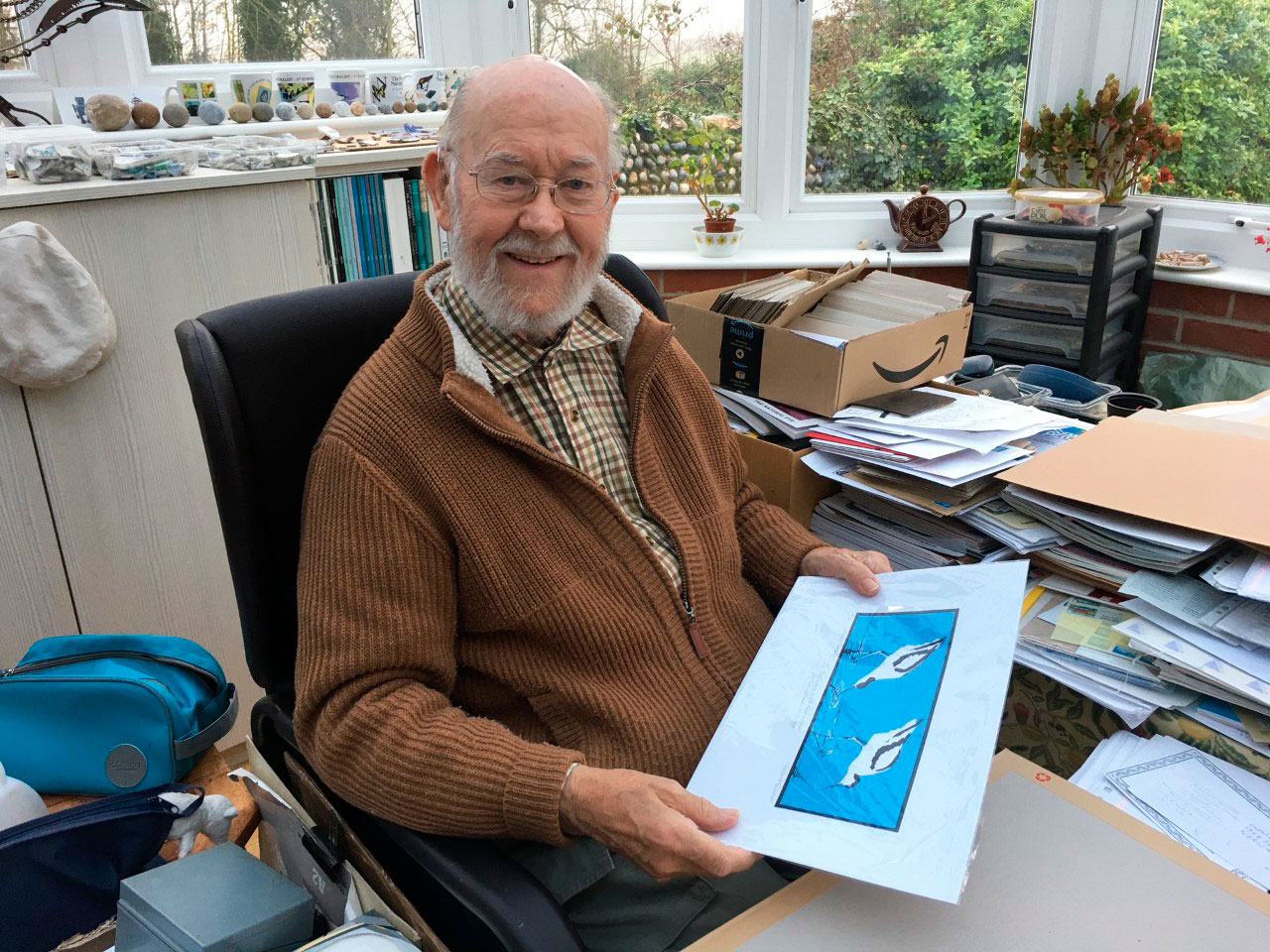

Robert Gillmor remained a prolific artist even until his final months, when he was known to work on projects from his hospital bed (Gillmor family).

Throughout his life, Robert offered advice to young wildlife artists and birders, many of whom he inspired to forge successful careers in the field. I first met him at an RSPB art exhibition in 1976 when I was 15 and, although I have never been an artist, we remained good friends for nearly five decades. Indeed, thousands of people will have met Robert at such exhibitions and experienced his quiet charm and self-effacing style. I doubt he ever offended anyone in his entire life!

Few people can match his humility and maybe none will ever match his bird art achievements. An artist to millions, friend to thousands and a mentor to hundreds. Having first been inspired by him when I was 15, I feel so lucky to count myself in the latter category.

Robert is survived by Susan, his children Emily and Thomas, and his grandchildren Jude, Amy, Angus and Isabelle.