For many years, the ability to age and sex birds was restricted to ringers, privileged enough to examine birds up close in the hand. But with massive advances in optics and especially digital photography, the opportunity is now open to all. But with the standard reference works often hard to digest and many not able to get out with ringers to share their skills, this can be a steep learning curve.

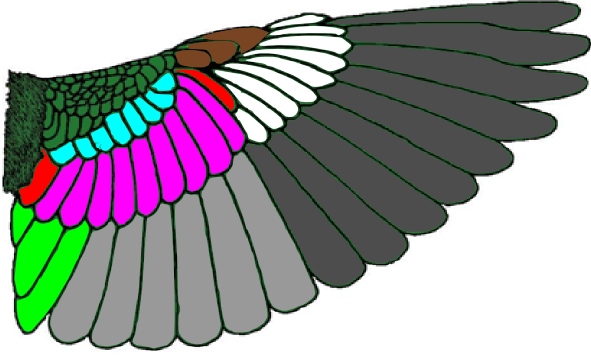

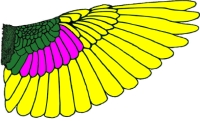

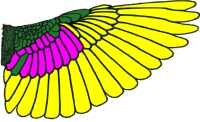

In many ways, the key to ageing birds is simply to have a good understanding of moult patterns, and of why, how and when birds do this. The simple guide below will guide you through the basics, but you'll need to understand the standard terminology for some of the feather tracts, so study this stylised wing.

The main feather tracts we'll be talking about are lesser coverts (dark green), which cover the bases of the median coverts (pale blue), which cover the bases of the greater coverts (pink), which cover the bases of the secondaries (pale grey). The tertials (pale green) act as if inner secondaries. The alula (brown) covers the bases of the primary coverts (white), which cover the bases of the primaries (dark grey). Shown in red are the carpal covert and the inner greater covert, both of which often moult out of sequence and independently. (Graphic redrawn from Jenni & Winkler 1994, coloured Graham Austin.)

Why moult?

The first question is an obvious one — why moult at all? For adult birds, the rigours of migration, raising broods of chicks and just living your life (or avoiding having it ended) all take their toll on feathers. Exposure to UV light will also weaken feathers, as will disease, the attentions of parasites and accidental damage.

Moulting adult White Wagtail, showing obvious contrast between the old, brown primaries and secondaries, and the replaced, black inner primaries. Note also the replaced wing coverts and tertials and old alula. (Photo: Dawn Balmer.)

Robin, Thetford, Norfolk. I don't think we need to point out why this bird needs to moult! (Photo: David Lord)

The stakes are rather different for a young bird, though. For any bird, the most vulnerable time of their life is their time in the nest, when they're unable to escape predators and also unable to feed themselves. So for a young fledgling, key to survival is leaving the nest as soon as possible. However, most passerines can't leave the nest naked, so a fledgling must grow the minimum feathers required to fledge. It saves energy in this process by growing narrow, pointed, poor-quality feathers. These are often cryptically coloured as well, especially in ground-feeding birds such as thrushes and chats.

Note the obvious differences between the primary coverts on these two Great Tits. The juvenile coverts are narrower, more pointed, with greener edging and a more washed-out base colour. (Photo: Dawn Balmer.)

Blue Tit, Barnstaple, Devon. Note the very open, loose feathering on this juvenile bird. (Photo: Roy Churchill)

What to moult?

Once a young bird has fledged, it can then start to think about its first moult. It needs to change its poor-quality, hastily grown juvenile feathers for a set that will allow it to survive through a migration, a winter and even into its first breeding season. The most important feathers to moult will be its body feathers, ensuring it has better insulation and a more attractive plumage for the spring. It is less essential to moult the flight feathers, as these are the best-quality feathers anyway.

The extent of the moult will partly depend on condition and the time available to moult, but, in order of decreasing importance, birds will moult: body feathers and lesser coverts, median coverts, greater coverts (but note that the inner and outer ones will moult independently and often out of sequence), tertials, alula and tail. Some birds, finches in particular, may moult some inner primaries, but this is still relatively uncommon, and these birds will also rarely moult secondaries and primary coverts. Interestingly, further south in Europe, where birds are less constrained by their environment, some juvenile finches will have a complete post-juvenile moult.

Greenfinch is one of the most likely species to moult a few primaries as part of a partial post-juvenile moult. These aren't moulted in the usual sequence and this bird is typical in moulting only primaries 4, 5 and 6 (counting from the inside). Note these have been moulted from the outside in, though, rather than inside out as in a standard moult. (Photo: Mark Grantham.)

When to moult?

For juvenile birds, the obvious time to moult is soon after fledging, when it's safe to lose their camouflage, but also in good time before the onset of winter weather. For migrants, most will obviously need to finish their moult before migration.

Adults needing to fit in a complete moult must also time it well. Moult is energetically expensive, so birds have to find the right window in the annual cycle. In winter they are more concerned with survival, spring is taken up with territorial and display duties and the summer is spent raising one, two or three broods of young. The only obvious window is thus autumn, which is when most adult birds will indeed moult. Most migrants also manage to fit in a moult in early autumn, but some, for example Grasshopper Warbler, will migrate with what might be quite tatty flight feathers, finishing their moult on the wintering grounds.

Some Grasshopper Warblers will start their moult before migration, but suspend it quite quickly. This bird only moulted two inner primaries before suspending. We know these are inner primaries as we can count eight other old primaries (including the hidden, vestigial outer one) and also six old secondaries. (Photo: Nick Bayly (SELVA).)

How does this help us age birds?

The chief use of an understanding of moult lies in being able to identify the state of moult the bird is in, which will identify its life stage. The concept is perhaps easiest to follow using an obvious example species: Blackbird. Consider a fledgling Blackbird, only recently out of the nest with loose, spotted brown plumage. In early autumn it will undergo a partial post-juvenile moult, where it will replace all of its body feathers and a majority of its wing coverts. Some birds will moult all of their greater coverts, but others will leave one or two unmoulted feathers, which will always be at the outside of the wing. But what it won't moult will be its wing feathers (primaries and secondaries), their corresponding primary coverts and tail. So there will always be an obvious contrast between the brown, retained juvenile-type greater coverts or primary coverts and the darker, replaced adult-type greater coverts. So seeing a bird with these two obvious generations of feathers tells us that this bird has undergone a partial moult. For Blackbirds, we thus know this is a first-year bird.

Blackbird, undisclosed site, Ayrshire (Photo: Mark Hope)

Blackbird, Minsmere RSPB, Suffolk (Photo: Jon Gibbs)

Jump forwards a few months to May, and our first-year bird will be into its first breeding season. It won't have undergone a second moult yet (it will have its first complete moult in its second autumn), so can still be aged by the two generations of feathers in the wing. We will be able to age this bird right up to the point when it undergoes its first complete post-breeding moult. After this it will be identical to much older birds.

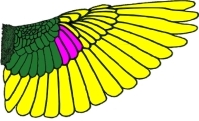

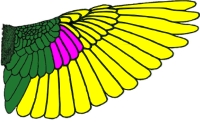

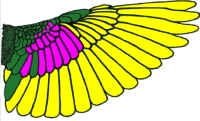

Following a partial post-juvenile moult, a bird will show two obvious generations of feathers right through to the point when it will undergo its first complete post-breeding moult. The period shown in blue indicates when a bird will show two generation of feathers, with the period in green when it shows just one generation. (Graphic: Mark Grantham.)

Blackbird, Ulley Reservoir CP, South Yorkshire (Photo: John Gray)

This same principle will apply to most passerines, though there are a small group of birds that do something different. A few species have a complete post-juvenile moult, hence are indistinguishable from adults that have undergone a complete post-breeding moult. This group includes Long-tailed Tit, House and Tree Sparrow, Starling, Bearded Tit, Corn Bunting, Skylark and Woodlark. Interestingly, these are all members of much larger families where most other species are resident in the tropics. In these areas juvenile birds are less constrained by their environment, so can afford to undergo a complete moult as routine, so perhaps this is simply a trait from their ancestry.

Both adults and juveniles of a few other species will also undergo a complete moult on the wintering grounds before a return migration, so species such as Willow Warbler and most of the Acrocephalus and Locustella warblers will all return in uniformly fresh plumage.

Blue Tit

These same principles apply to many passerines, and you don't need to see much of the wing to appreciate the differences.

Blue Tit, New Forest, Hampshire. This unmoulted juvenile bird is characterised by its yellow face and the greenish cast to all of its coverts. Note as well the loose structure to the body feathers, especially along the belly and flanks. (Photo: Lee Fuller)

Blue Tit, Wayoh Reservoir, Lancashire (Photo: John Barlow)

Blue Tit, Warrington, Cheshire (Photo: Neill Carden)

Blue Tit, undisclosed site, Greater Manchester. This adult bird shows a completely uniform wing, with greater coverts, alula and primary coverts all blue and of the same generation. (Photo: Sue Tranter)

Siskin

Once again, the same principles apply for Siskin, and comparing juvenile and adult males really picks out these differences.

Siskin, Ebbw Vale, Gwent (Photo: Mike Warburton)

Siskin, Clara Vale LNR, Durham. Although this bird is much duller than the juvenile above, it is almost certainly an adult. All of the coverts and tertials are adult-type and there is no contrast between the base colour of the primary coverts and greater coverts. Also compare the extent of yellow in the primaries and, in particular, the base colour of the primaries on these two birds. (Photo: Ron Hindhaugh)

Ageing vagrants

Moult patterns for most temperate (hence often migratory) passerines are similar, so can be applied to help in ageing vagrants. Birds breeding at higher latitudes will often have a shorter breeding season, so juveniles will generally have less time to moult before migrating. They are thus more likely to show a greater number of retained juvenile-type feathers than more southerly species.

Richard's Pipit, St. Mary's, Isles of Scilly (Photo: Gary Thoburn)

Richard's Pipit, West Kirby, Cheshire (Photo: Sean Gray)

Richard's Pipit, Pleinmont, Guernsey. This bird is rather interesting in that it will now be forced to regrow all of its secondaries and tertials, and most of the greater coverts on one wing. Interestingly, of the greater coverts that weren't plucked, there are still two generations of feather, hence this is a first-year bird. But once it has regrown the missing feathers it will have three generations of greater coverts! (Photo: Chris Bale)

Blyth's Pipit, Fair Isle, Shetland (Photo: Deryk Shaw)

Other aids to ageing

Aside from plumage patterns, there are other useful pointers to ageing in some birds. As mentioned previously, juvenile-type feathers are generally narrower and more pointed. This can often be picked out in the field, and is even more obvious if the bird has moulted some tail feathers and retained others. Birds will generally moult the central pair (or pairs) of feathers, as these are the ones which become most worn, leaving the outer feathers unmoulted.

This first-year male Chaffinch has only moulted a single central tail feather, although this is more likely to be through accidental loss. The difference in shape and colour is obvious, though, and the dark smudge on the adult-type feather is a good feature. (Photo: Andy Leech.)

Many feathers will also show 'growth bars', which reflect the protein that could be put into growing the feather on any one day during the moult. In especially harsh conditions, when a bird can't feed (or be fed), the growth bar for that day will be very obvious indeed, appearing as a 'fault bar' in the feather. These are most obvious in the tail, which grows the quickest, and the use of this in ageing is that in the nest the feathers will grow at the same time, so the fault bar will always fall the same distance from the tip of the feather. When the tail is moulted sequentially, the fault bar will be at different distances from the feather tip on each pair of feathers, appearing as a V-shape.

This Sedge Warbler shows an obvious fault bar, and although it is very rounded, this reflects the shape of the tail, with the bar being the same distance from all the feather tips. This tells us that these feathers were grown at the same time (i.e. in the nest) so it is a first-year bird. (Photo: Nick Bayly (SELVA).)

Many species will show subtle changes in iris colour over the course of the autumn and winter. This is most obvious in species such as Dunnock (olive-green developing to red), Whitethroat (dull-brown developing to straw-coloured) and Lesser Whitethroat (dark grey developing to paler with a crescent).

These two Whitethroats clearly show the difference in iris colour. The bird on the left is a first-year and the bird on the right is an adult. (Photo: Nick Bayly (SELVA).)

Have a go yourself

Have a look at the following birds and try to work out their ages. All should be possible on what you can see here.

Blackbird, Sedbergh, Cumbria (Photo: Janet)

Great Tit, New Forest, Hampshire (Photo: Lee Fuller)

Siskin, Lackford Lakes SWT, Suffolk (Photo: Adi Sheppard)

Naumann's/Dusky Thrush, Japan (Photo: Ambrosini)

Siberian Thrush, Natural Surroundings NR, Norfolk (Photo: John Miller)

Black-throated Thrush, Hartlepool Headland, Cleveland (Photo: Mark Newsome)

Reference

Jenni, L. & Winkler, R. (1994). Moult and ageing of European Passerines. T&AD Poyser, UK.