A study carried out in Extremadura, Spain, has shown Common Redstart to be a master of mimicry. Demonstrating astonishing skill, the species manages to imitate birds as varied as Grey Heron, Red-legged Partridge, Booted Eagle, Eurasian Magpie, European Bee-eater and Golden Oriole. It even manages to squeeze three different wader species into a single three-second phrase.

Many bird species are regular mimics. Some have gained worldwide renown for this skill, like Common Starling in Europe, Northern Mockingbird in North America, Tui in New Zealand or Superb Lyrebird in Australia. Somewhat less celebrated for its mimicry, however, is Common Redstart, although this skill does get a passing mention in some hard-copy or online literature. Special mention here must go to the outstanding 1994 study by Jacques Comolet-Tirman.

As well as being one of Europe's most beautiful summer migrants, Common Redstart is also one of the region's finest songsters (Kit Day / kitday.smugmug.com).

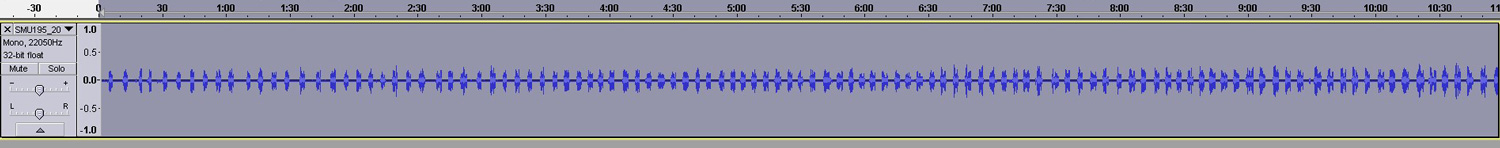

Common Redstart is one of our most persistent and tireless singers; in Supra-Mediterranean regions it will sing almost non-stop in April, May and even into June, churning out seven to nine phrases per minute in full song. A complete phrase lasts about three seconds, and, with almost clockwork-like regularity (see graph 1) it almost always leaves a pause between each phrase of about 4.5 seconds.

Its song nearly always starts the same way, with two or three repeated drawled notes, as though the bird found it hard to start up each time. This opening is sometimes preceded itself by a whistle; other times the notes might be drawn out into a kind of stutter. The second part of the song, following without a break, is a squeaky twitter without any apparent pattern to it. The silence it invariably leaves between each phrase tends to increase this sense of awakening from a short stupor each time and dragging itself back into action. Although the song as a whole is so amorphous, this drawly effect at the start and its regular sequence of song and silence give it a very distinctive sound, making it immediately recognizable from a great distance. The timbre is somewhat similar to that of Chaffinch and Tree Pipit but the overall structure, with the rather stereotyped start and a completely freeform second part resembles few other species; maybe the most similar is Pied Flycatcher's.

Graph 1: spectrogram of a male Common Redstart's song, clearly showing the clockwork-like regularity in its sequence of song and silence.

On 7 May 2020 Godfried Schreur and his son Pedro set up recorder in a cork oak to record a male in full song for several hours, starting at 6.17 am (67 minutes before sunrise). The recording site was a cork-oak wood with medium-sized trees in the Sierra del Lugar in La Codosera, a picturesque town bordering on Portugal in the north-west of the Extremadura province of Badajoz, Spain. The population of redstarts here stretches along the wooded hills of the medium- to high-part of the Gévora/Xévora river basins, blending in with a Portuguese nature reserve called Parque Natural da Serra de São Mamede.

When played back, the recording turned out to contain an astounding number of imitations. The more they studied the second part of the song, a sequence of three to seven well-differentiated fragments, the more imitations came to light. On a few occasions, it also included mimicry at the start of the phrase.

The three authors, all experts with a wealth of experience in identifying species by their song, analysed the redstart's 451 phrases in the 53-minute recording. The first phrase of top-quality song included in the analysis occurred at 6.29 am, 55 minutes before sunrise.

Imitations of at least one species were detected in 404 of the 451 analysed phrases (90%). In only 47 did it prove impossible to identify any species at all. On 13 occasions four different species were imitated in the same phrase, the maximum number recorded in a single phrase.

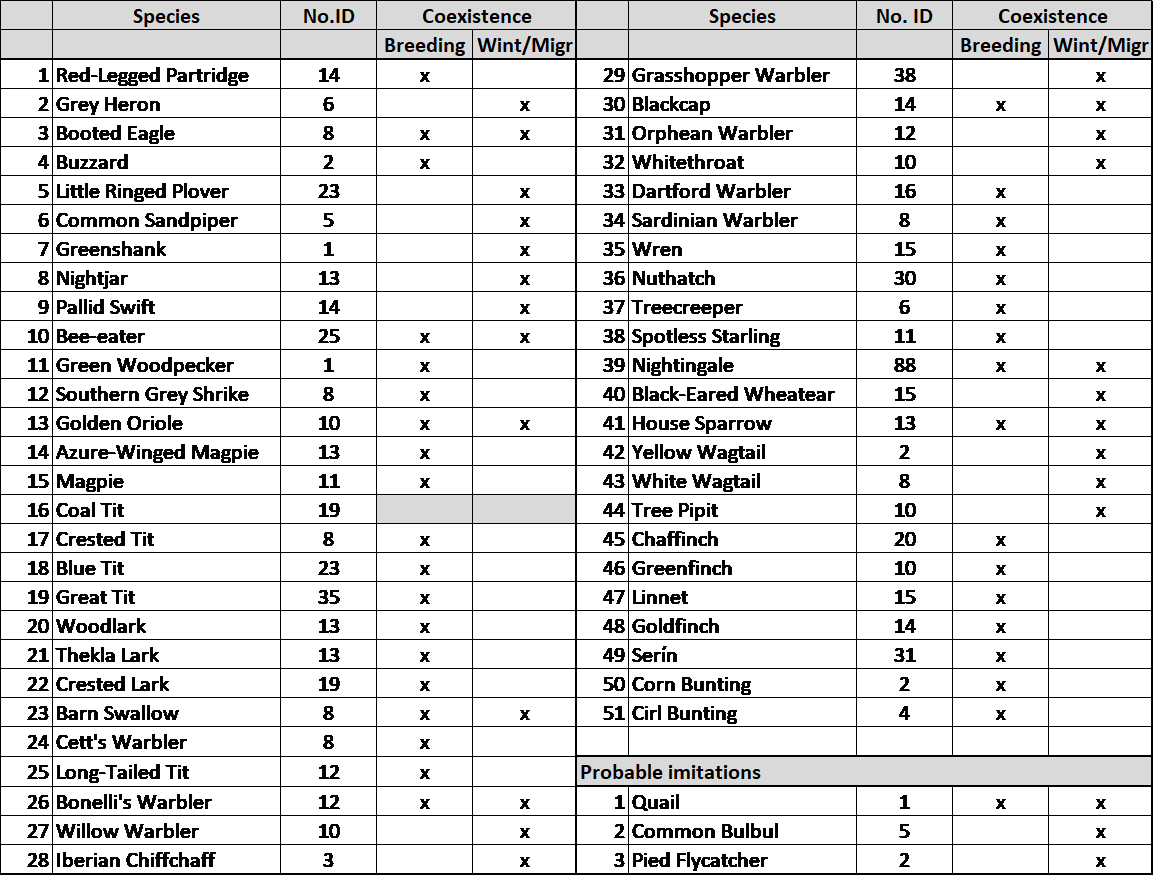

After a painstaking screening and re-listening process the three authors mutually agreed to class 51 species as "certain", with three other species classed as "probable", and 21 "possibles" ruled out after the screening process.

Table 1: Species imitations rated as certain (51) and probable (3). 'No. ID' refers to the number of times detected. Coexistence: breeding refers to species breeding in this particular redstart's territory (nearby neighbours with territories less than 2 km away), while 'Wint/Migr' concerns species sharing wintering zones or migrations routes with the western European redstart population.

The results revealed that Common Nightingale was the most commonly mimicked species. Grasshopper Warbler, Great Tit, European Serin and Eurasian Nuthatch are other regular imitations. Some species, on the other hand, were recorded only once.

The quality of the imitation varies from species to species. At the top end are species as varied as Grey Heron, Red-legged Partridge, Booted Eagle, Magpie, European Bee-eater and Golden Oriole, all of which the redstart mimics with consummate skill and clarity. Other species have to be ferreted out with greater difficulty from the apparently freeform twitter of the second part of the song. Even so, the tone, frequency (in kHz) and duration of the mimicry usually matches the models with striking fidelity. Rhythm is sometimes more of a struggle; small wonder when each imitation lasts around 0.3 seconds.

Sometimes, however, especially with Western Orphean Warbler, the rhythmic dexterity it can pack into these 0.3 seconds defies belief. Western Orphean Warbler has a syncopated rhythm unlike any other bird. The redstart on many occasions is capable of suddenly imitating this unique rhythm in the briefest space of time, breaking up the more standard rhythm of its song otherwise and carrying on after the 'interruption' as though it never occurred.

The redstart sometimes imitates both the call and the song of the same species. Examples are Eurasian Wren, Dartford Warbler, Common Whitethroat and Golden Oriole. In the case of House Sparrow, which has no song to speak of, the redstart always combines the straightforward chirp with this species' ratchet-like sequence of chitters.

Of the 54 species detected, 38 share breeding territories with the redstart or live very close by, less than 2 km from the edge of the cork-oak wood. Sixteen of the species, however, do not share the mimic's territory. Almost all of these do share wintering areas with Common Redstart or overlap with it on migration, such as Willow Warbler, Iberian Chiffchaff or Yellow Wagtail. Worthy of special mention here is Common Bulbul, rated only as a probable imitation due to our inexperience with the species. This species lives in the redstart's wintering grounds and along a large part of its migration route.

Only one of the imitated species, Coal Tit, neither shares breeding territory with this particular Common Redstart nor wintering areas or migration routes (if we rule out the North African population). But this sedentary species is a distant neighbour of the Redstart, with its nearest breeding territories in a pinewood more than 6 km away, where the two species do overlap. A possibility to explain this might be that this particular redstart was born in or near the Coal Tit's pinewood.

Species mimicked by the single studied Common Redstart ranged from Grey Heron to Great Tit (Morten Scheller Jensen).

Certain breeding species of the Sierra del Lugar, which the redstart must hear every day, are striking and thought-provoking absences from the roster of imitated species. These include Tawny Owl, Woodpigeon, Collared Dove, Red-necked Nightjar, Hoopoe, Common Cuckoo, Mistle Thrush, Western Subalpine Warbler and Rock Bunting.

Many of the aforementioned missing species have distinctive songs and for this very reason their absence is so surprising. Monosyllabic songs or calls, however, as well as very high-pitched and short songs would always be harder to pick out in the redstart's song; the same goes for other songs that resemble it to some degree, like that of European Robin. The fact of a species not having been detected, therefore, does not necessarily mean that it is never imitated, only that we have been unable to detect it. It should also be pointed out here that none of the authors has any great experience with the African species that Common Redstart winters alongside.

Several stock sequences have been recorded, with the same string of species being repeated regularly. Nightingale's chug chug chug phrase, for example, is often followed by the chromatic cadence of a Willow Warbler. Special mention here must go to the set of three wader species combined in a single phrase: Common Sandpiper, Little Ringed Plover and Greenshank.

An analysis of the recordings has shown that this particular redstart does not tend to react immediately to the birds that happen to be singing around it at each moment. A Chaffinch or Nuthatch singing strongly alongside, for example, does not seem to trigger an instant imitation of that species in the redstart's song.

Jacques Comolet-Tirman's 1994 Fontainebleau study analysed over 1,300 phrases of 36 different Common Redstarts, detecting a maximum of 35 species imitated by a single male. This article rules out the possibility of African imitations and suggests that redstarts also learn songs from species met on migration.

Judging from the sheer number of recognizable imitations in our study, and the likelihood of more unrecognizable species being included too (including even African species), we suggest that the entire second part of Common Redstart's song is probably an amalgam of different imitations. To confirm this hypothesis, a more in-depth analysis would be needed from ornithologists from different parts of the world or using advanced birdsong ID software.

This study seems to confirm that Common Redstart picks up its imitations directly from the models, whether in the breeding or wintering area or on passage. There are as yet no results to suggest that it might also learn imitations indirectly from its parent or other neighbouring males, though this cannot be ruled out.

It would likewise be interesting to study in greater depth the linked imitations and fixed sequences to find out whether the associations spring from shared habitats, particular moments of coexistence in its lifecycle or other unknown criteria. Other moot points are the triggers that prompt it to mimic a given species at a given time or the question of whether the repertoire might change as the bird ages or the breeding season progresses.

As for the overarching question of why it imitates at all, it would seem likely that the greater the number of species any male imitates, and the higher the quality of these imitations, the more attractive this male will prove to females or more daunting to rival males, as in the famous 'Beau Geste' effect – although we should perhaps also keep an open mind about the possibility of their doing it purely for their own enjoyment.

We are happy to lend out the recordings of this redstart's song for anyone else to offer their own take on the matter and add further insight.

References

Comolet-Tirman, J. 1994. Le chant imitatif du Rougequeue à front blanc (Phoenicurus phoenicurus): une étude en forêt de Fontainebleau, Seine-et-Marne, France. Nos Oiseaux, 42: 267–277.

Comolet-Tirman, J. 1994. Does the redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus mimic bird species heard during migration? Bioacoustics 6(1): 73-79.

Constantine, M & the Sound Approach. 2006. The Sound Approach to Birding: a guide to understanding bird sound. The Sound Approach, England.

Ruiter, C J S. 1941. Waarnemingen omtrent de levenswijze van de Gekraagde Roodstaart, Phoenicurus phoenicurus (L). Ardea 30: 175–214.

de Vos, D. 2017. Veldgids Vogelzang: Vogels Herkennen aan Hun Zang en Roep. KNNV Uitgeverij, Zeist.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jesús Calle Vaquero, Samuel Langlois and Pedro Schreur Cordero.