Key featured species

- Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis

- Ruff Philomachus pugnax

The problem

A peculiar bird best noted for its bizarre lekking displays and its eccentric and extremely variable summer plumage, Ruff is most familiar in Britain in its juvenile and winter plumages. In the former, it can be confused with Buff-breasted Sandpiper, a rare North American visitor that also has a lekking display.

The solutions

Juvenile Ruff

Short-billed and small-headed, with a long neck, bulky body and long legs, Ruff is a wader that picks at the ground with a deliberate action as it strides purposefully along a muddy shoreline. It is oddly silent, even when indulging in its strange displays.

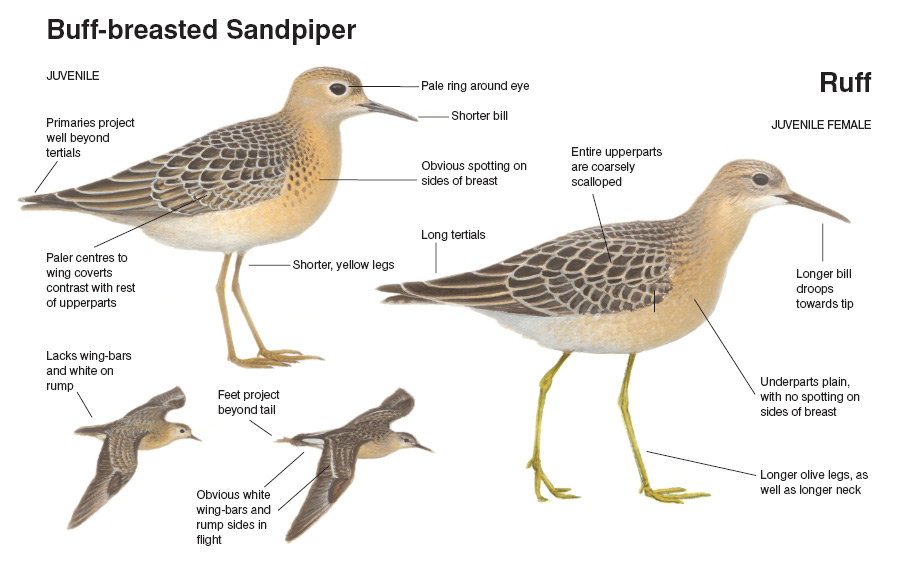

Ruffs lack obvious features, but juveniles are best identified by a combination of distinctive orangey-brown underparts, which become whiter on the belly and vent, and strongly scalloped upperparts. The scalloping effect is produced by narrow pale fringes to the back feathers, scapulars, wing coverts and tertials. In flight, they have two distinctive features: a noticeable whitish wing-bar that becomes broader and more diffuse across the primaries, and two oval white patches on either side of the base of the tail, on the lateral uppertail coverts. The leg colour is a dull olive-green.

The important point to make about Ruff, particularly in relation to its separation from Buff-breasted Sandpiper, is that there is a striking size difference between males and females. Small females may be only two thirds the size of the largest males, and males may be 75 per cent heavier. Small female Ruffs are close to larger male Buff-breasts in size, which in turn are about 10 per cent larger than their mates.

Juvenile Buff-breasted Sandpiper

Juvenile Buff-breast is superficially similar to a small juvenile female Ruff in that it is similarly proportioned and rather featureless, apart from its buff underparts and strongly scalloped upperparts. Despite this, the two species are easily separated.

It is helpful to think of Ruff as a medium-sized wader, whereas Buff-breast is really a small wader, sometimes associating in Britain with flocks of Ringed Plovers and Dunlins, from which it does not stand out on size alone.

Buff-breast has a shorter neck than Ruff, and when feeding it looks more horizontal and longer-bodied. Being a long-haul migrant, it has long primaries that make its rear end look tapered. Its primaries, unlike those of a Ruff, project well beyond the tertials, the primary projection being about half the overlying tertial length.

The head is rather square and the large, dark eye, enhanced by a diffuse pale eyering, stands out in the rather bland face. The crown is delicately streaked and there is neat spotting down the sides of the breast. The underparts are paler, less orangey-buff than those of juvenile Ruff, and they are more evenly coloured right down to the lower belly, fading to white on the undertail coverts. As in Ruff, the upperparts are scalloped, but very finely and delicately. If in doubt, check the legs: these are noticeably pale ochre-yellow, unlike the dull olive-green of juvenile Ruff’s legs.

The other obvious difference becomes apparent in flight: the wings, rump and tail are plain, lacking Ruff’s wing-bar and white patches at the base of the tail. In addition, Buff-breast looks more typically like a small wader in flight – perhaps rather plover-like – lacking Ruff’s attenuated rear with feet projecting noticeably beyond the tail. It also lacks Ruff’s long wings and easy, languid flight action.

When feeding, Buff-breast is more energetic than Ruff, walking quite actively on slightly flexed legs and constantly bobbing its head back and forth. Unlike Ruff, it does not wade out into the water and immerse its head to feed. It is also much less obtrusive and is easily overlooked, particularly on pale-coloured mud. It is usually very approachable, often choosing to squat down low rather than take flight.

It prefers dry, short grass habitats such as golf courses, airfields and the drier sections of saltmarshes, and even at reservoirs it tends to prefer the drier areas towards the top of the bank. It sometimes occurs in small parties, with as many as 15 on St Mary’s, Scilly, in 1977, a year that saw a record 54 in Britain.

Adult Ruff

In summer, females are brownish, mottled and spotted with black, but there is considerable individual variation in the patterning.

In winter plumage, Ruffs are greyish, the upperparts being more diffusely scalloped than those of autumn juveniles. They show white feathering at the base of the bill and some males have quite extensive areas of white on the head and neck; indeed, some are completely white-headed, producing a very distinctive appearance, even at a distance. Adults have bright pink or orange legs and bill base, the former sometimes causing confusion with Common Redshank. First-winters, however, retain their dull olive legs. On autumn migration, Ruffs are usually associated with freshwater marshes, lakes and reservoirs, but in winter they are much more likely to be found in fields, often feeding with European Golden Plovers.

Adult Buff-breasted Sandpiper

The few adults seen in Britain are usually in late spring and late summer, being extremely rare in September when the juveniles appear. They are similar to juveniles, but are easily aged by the thick and diffuse buff fringing to their upperpart feathers.

Did you know?

Buff-breasted Sandpiper has a peculiar lekking display in which the males flash open their wings to reveal striking white underwings. Several females may approach a favourite male, which corrals them by holding its wings in a parabolic shape, all the while pointing its bill skywards, shaking its body up and down and making soft clicking noises. This remarkable display was prominently featured on David Attenborough’s Life of Birds series on television.

Adults migrate mainly through central North America, but a significant minority makes a direct flight down the Atlantic from north-eastern Canada and the United States to northern South America. From there they continue south to wintering grounds on the pampas and other grasslands of Argentina, southern Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay.

This route is the source of British vagrants. As a consequence of its long-haul oceanic migration, Buff-breast is rare down the North American eastern seaboard and, paradoxically, the species is more familiar to some British birders than it is to many North Americans!

Like the Eskimo Curlew, Buff-breasted Sandpiper was devastated by commercial hunting in the 19th century and its world population remains low to this day, estimated at just 15,000-25,000 birds; it may still be declining. In recent years, its status has been affected further by the conversion of much of the Argentinian pampas to agricultural land.