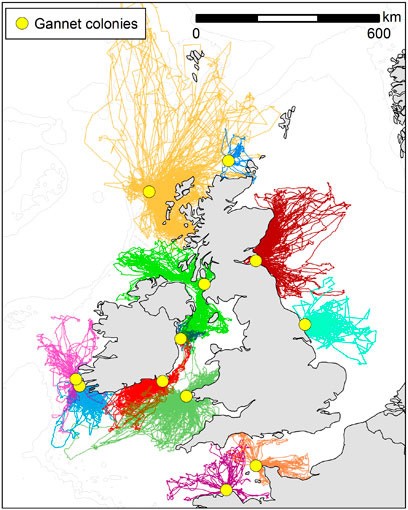

New research shows that Gannets only feed in areas belonging exclusively to their colony, preferring to leave those belonging to neighbours alone. The study, published in Science on 6th June 2013, was an international project led by the universities of Leeds and Exeter. The researchers used small satellite tracking devices attached to 184 Gannets from different colonies around the UK to build up maps showing the birds' flight paths. Dr Keith Hamer, from the University of Leeds and principal investigator of the project, said: "It quickly became clear when we started mapping the data that something interesting was happening. Areas of sea used by birds from adjacent colonies were neatly abutting but not overlapping, with no spaces between them either".

Satellite-tracked Gannet food flight paths (Wakefield et al.).

The team think there are two reasons the birds follow such set routes. The first is a question of maths. Dr Ewan Wakefield from the University of Leeds, joint lead author of the study, explained: "Gannets dive from the air into the water and feed on prey close to surface. They rely on predatory mammals like dolphins driving prey to the surface to make them accessible. But once Gannets start diving in, the prey take evasive action, so feeding opportunities don't last long. The important thing for Gannets is to be one of the first arriving at the feeding area. If other birds from another colony are more likely to get there first, there's no pay-off."

Dr Thomas Bodey, from the University of Exeter, also joint lead author of the study, says that competition for food cannot be the only explanation for such clear differences between the colonies' feeding patterns. "It's likely that cultural differences also play a part in the birds' behaviour. As with humans, birds have favoured routes to travel, and if new arrivals at a colony follow experienced old hands then these patterns can quickly become fixed, even if other opportunities potentially exist."

"There's no conscious realisation that the bird feeding next to them is from their own or another colony. Some colonies have 60,000 birds so it would be impossible for a Gannet to tell. At sea they're just looking out for themselves," Hamer explains. "Natural selection will favour individuals who can find good feeding opportunities, but if a Gannet keeps going somewhere that other birds from another colony are getting to first, it won't do very well."

Plunge-diving Gannet (Photo: John Anderson)

The research could have wider implications for our understanding of animal behaviour as, until now, individual colonies having exclusive access to small foraging areas was a trait known mainly among insects. Professor Stuart Bearhop of the University of Exeter said, "If you look at some species, like ants, individuals aggressively defend an area around their colony to keep others away. That results in a way of foraging in ant colonies where feeding areas meet but don't overlap, as the aggressive behaviour means they all steer clear of each other."

Hamer added "The accepted view is that in species that don't show such aggression their foraging ranges would naturally overlap."

But this new discovery means scientists may now have to reassess whether other animals show this behaviour. "It's possible that this is particular to Gannets, but now we can start to look at all the other species that don't defend their territory, from bees to bats."

Wakefield ED, Bodey TW et al. 2013. Space partitioning without territoriality in Gannets. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.1236077

Original article here.