Bird beaks act as air conditioners

6a7947cc-7e49-405c-a900-15f7a4b82aeb

A new study has found that the insides of birds' beaks are filled with complex structures to help them meet the demands of hot climates.

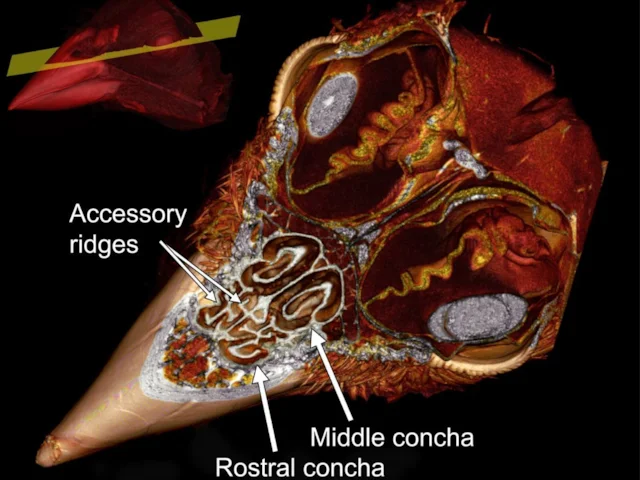

Birds' beaks come in an incredible range of shapes and sizes, adapted for survival in environments around the world. Nasal or rostral conchae are complex structures inside bird bills that moderate the temperature of air being inhaled and reclaim water from air being exhaled.

Raymond Danner of the University of North Carolina Wilmington and his colleagues from Cornell University and the National Museum of Natural History used computed tomography (CT) scans to examine the conchae of two Song Sparrow subspecies — one that lives in warm, dry sand dunes and another that lives in moister habitats further inland.

In this first comparison of conchae structure from birds living along a moisture gradient, the conchae of the dune-dwelling sparrows had a larger surface area and were situated farther out in the bill than those of their inland relatives, hypothetically increasing their beaks' ability to cool air and recapture water.

Danner and his colleagues used Song Sparrow specimens that were collected in Delaware and the District of Columbia, and preserved in ethanol and iodine to help soft tissues show up in scans. The contrast-enhanced CT scans they used to visualize the insides of the sparrows' bills is a relatively new technique that is allowing researchers see the details of these soft, cartilaginous structures for the first time.

"We had been studying the function of the bird bill as a heat radiator, with a focus on heat loss from the external surface and adaptation to local climates, when we began to wonder about the thermoregulatory processes that occur within the bill," says Danner. "I remember the entire team assembled for the first time, huddled around a computer and looking in amazement at the first scans. The high resolution scans revealed many structures that we, as experienced ornithologists, had never seen or even imagined, and we were immediately struck by the beauty of the ornately structured anterior conchae and the neatly scrolled middle conchae."

"This study highlights the remarkable complexity of the rostral conchae in songbirds. This complexity has gone largely unnoticed due to the ways in which most birds are collected and preserved," according to Jason Bourke of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (who was not involved in the research). "Thanks to the use of innovative techniques like diceCT, we are now able to really appreciate just how complicated bird noses can be."

Reference

Danner, R M, Gulson-Castillo, E R, James, H F, Dzielski, S A, Frank III, D C, Sibbald, E T, and Winkler, D W. 2017. Habitat-specific divergence of air conditioning structures in bird bills. The Auk 134: 65-75 doi: 10.1642/AUK-16-107.1

Birds' beaks come in an incredible range of shapes and sizes, adapted for survival in environments around the world. Nasal or rostral conchae are complex structures inside bird bills that moderate the temperature of air being inhaled and reclaim water from air being exhaled.

Raymond Danner of the University of North Carolina Wilmington and his colleagues from Cornell University and the National Museum of Natural History used computed tomography (CT) scans to examine the conchae of two Song Sparrow subspecies — one that lives in warm, dry sand dunes and another that lives in moister habitats further inland.

In this first comparison of conchae structure from birds living along a moisture gradient, the conchae of the dune-dwelling sparrows had a larger surface area and were situated farther out in the bill than those of their inland relatives, hypothetically increasing their beaks' ability to cool air and recapture water.

Danner and his colleagues used Song Sparrow specimens that were collected in Delaware and the District of Columbia, and preserved in ethanol and iodine to help soft tissues show up in scans. The contrast-enhanced CT scans they used to visualize the insides of the sparrows' bills is a relatively new technique that is allowing researchers see the details of these soft, cartilaginous structures for the first time.

"We had been studying the function of the bird bill as a heat radiator, with a focus on heat loss from the external surface and adaptation to local climates, when we began to wonder about the thermoregulatory processes that occur within the bill," says Danner. "I remember the entire team assembled for the first time, huddled around a computer and looking in amazement at the first scans. The high resolution scans revealed many structures that we, as experienced ornithologists, had never seen or even imagined, and we were immediately struck by the beauty of the ornately structured anterior conchae and the neatly scrolled middle conchae."

"This study highlights the remarkable complexity of the rostral conchae in songbirds. This complexity has gone largely unnoticed due to the ways in which most birds are collected and preserved," according to Jason Bourke of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (who was not involved in the research). "Thanks to the use of innovative techniques like diceCT, we are now able to really appreciate just how complicated bird noses can be."

Reference

Danner, R M, Gulson-Castillo, E R, James, H F, Dzielski, S A, Frank III, D C, Sibbald, E T, and Winkler, D W. 2017. Habitat-specific divergence of air conditioning structures in bird bills. The Auk 134: 65-75 doi: 10.1642/AUK-16-107.1