Provoked by recent events and debates surrounding which legacies we choose to honour, there has been renewed controversy and discussion concerning the vernacular name McCown's Longspur and other eponyms in ornithology. A recent (open access) paper published in the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club by Matthew Halley, from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, turns the spotlight on the American ornithologist and illustrator John James Audubon. Audubon is a name familiar to birders and ornithologists the world over, immortalised in Audubon's Shearwater and Audubon's Oriole, and, of course, in the National Audubon Society, which is one of the world's oldest conservation organisations.

Ten years ago, Halley came across several of Audubon's unpublished letters that had lain in a private collection in Philadelphia for more than 150 years. Among them the original prospectus for what became The Birds of America. The letters had been written to the corresponding secretary of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP), and were stored at the latter's family home, Wyck House, after his death. There, they went unnoticed by Audubon scholars until 2010, when Halley became Wyck's resident caretaker and began to study Audubon's legacy. To place the letters in context, Halley initiated a systematic review of Audubon-related literature, and eventually uncovered a history that is radically different from the romantic vision of Audubon familiar to most of us.

Halley evidences that Audubon effectively defrauded his benefactors to raise the funds necessary to publish The Birds of America. Following alleged plagiarism in 1824, Audubon was rejected by the ANSP (at the time, the seat of ornithology in the United States). Thereafter, Audubon took his paintings to Europe, where fewer experts in American ornithology could exert scrutiny and he was, at least initially, given a free pass.

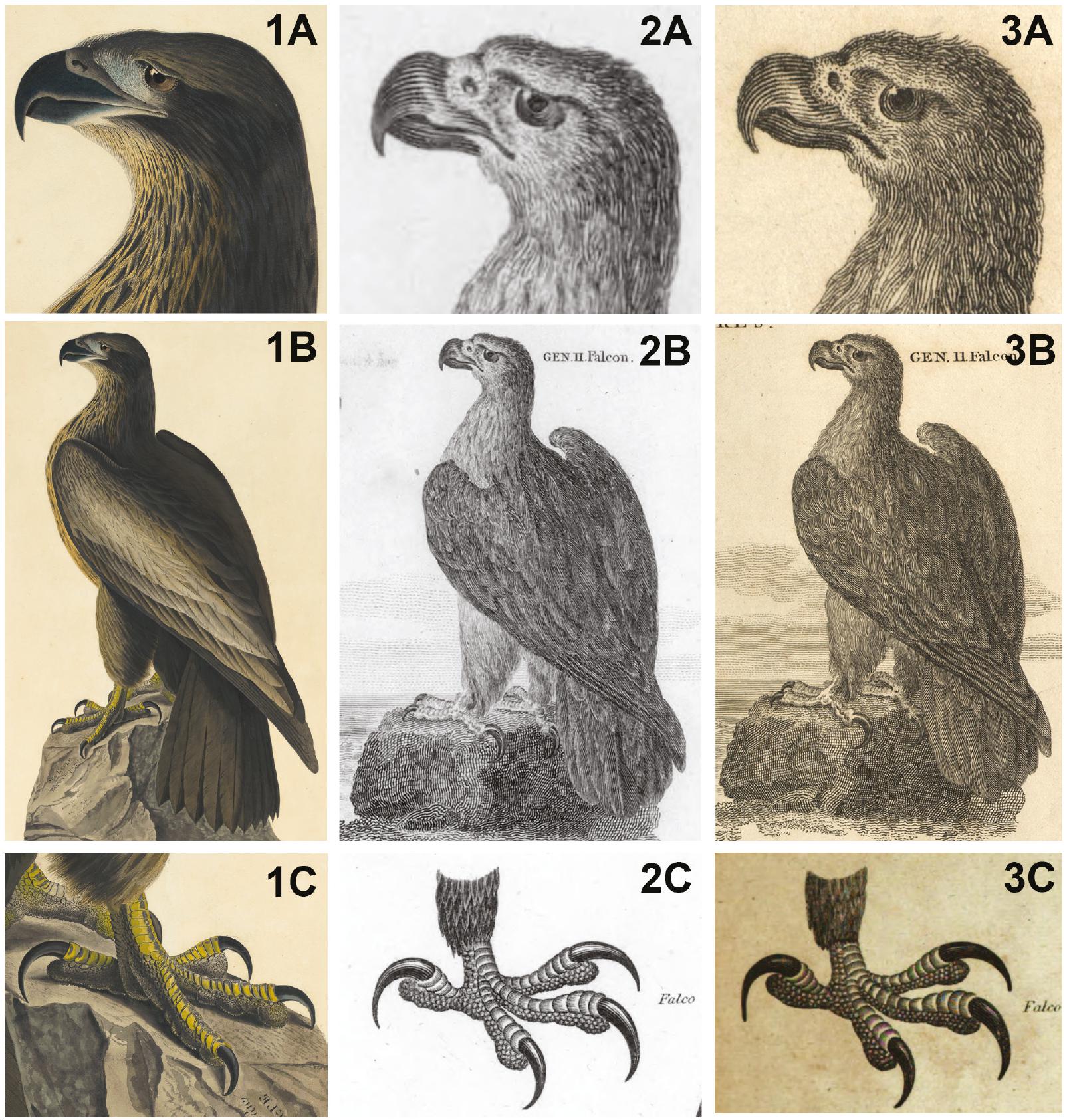

In 1826, Audubon exhibited in Liverpool and Edinburgh, with the first painting on display depicting a massive eagle. Named the 'Bird of Washington', Audubon claimed it was an undescribed species closely related to the familiar Bald Eagle, but readily distinguished by its much larger size and unique foot and bill morphology. Audubon claimed that his paintings were the result of "attentive examination of the objects portrayed during a long series of years". Conversely, Halley presents compelling evidence that the Bird of Washington was a fraud: not drawn from a specimen as Audubon claimed (and which Halley demonstrates never existed), but instead plagiarised from two images in The Cyclopædia, a work published in London more than 20 years earlier.

1A-C Audubon's 'Bird of Washington' (1826); 2A-B 'Golden Eagle' by Sydenham Edwards, published in the British version of The Cyclopædia (1802); 2C 'Falco Foot', (image inverted) published in 1812 of the British edition of Rees (1802-19); 3A-B 'Golden Eagle' re-engraved and published in 1806 of American edition of Rees (1806-20); 3C 'Falco' foot, re-engraved and published in the American edition (date uncertain).

The 'Bird of Washington' was the first new species described by Audubon and was also his most famous 'discovery'. It went on to serve as the foundation for European investment in his work (including by the British nobility and King George IV), his international fame and contemporary legacy. It was also the centrepiece of his fraudulent marketing strategy and a lie that he actively maintained until his death, sowing confusion among scientists and the public that has lasted until the present.

In addition to these alleged instances of plagiarism, Audubon scholars have revealed a case of probable specimen theft (Fries 2006: 189-90, Halley 2020a), fraudulent drawings and data given to Rafinesque (Markle 1997, Woodman 2016), complete or partial fabrication of his famous ringing experiment (Halley 2018a), the seemingly deliberate distortion of the timeline in his published writings (Halley 2015, 2018a, this study) and a case of suspected backdating of a painting (Pick 2004). There is also an interesting case of self-plagiarism; the image that accompanied the original description of Western Meadowlark (Audubon, 1844) was copied and modified from an image of a juvenile Eastern Meadowlark (Linnaeus, 1758) in the double-elephant folio (Pl 136), though the plate bears the false caption 'drawn from nature by J J Audubon' (Halley 2016, based on a drawing reproduced in Tyler 1993: 100).

The illustration of Red-winged Blackbird from Wilson's 'American Ornithology' (left; 1811) appears to have been plagiarised by Audubon (right; from 1829).

In another paper, Halley (2020) evidences that Audubon probably stole the type specimen of Harris's Hawk, pretended to be unaware of its collector and named it for Edward Harris (1799–1863) – a close friend and partial financier of The Birds of America. Its true collector – one of his subscribers – reportedly intended to name the species 'Morton's Hawk', after Dr Samuel Morton.

Why haven’t we heard these stories before? The 'Bird of Washington' is barely mentioned in the multiple popular biographies, and most ornithologists have assumed that Audubon innocently misidentified an immature Bald Eagle, despite the evidence that has accrued to the contrary. Halley documents that many of Audubon's contemporaries recognised his fraud, including both William Swainson and Charles Lucien Bonaparte, two of the most influential ornithologists of the day, but failed to expose him. "What has possessed the self-called friends of Audubon?", lamented George Ord (1781-1866), who was loyal to his mentor, Wilson, and to the tradition of specimen-based ornithology. "Are they determined to make him a great man in defiance of truth and common sense?"

Halley argues that the romantic story of Audubon that permeates biographies and social media is both inaccurate and ethically indefensible. Today, the name Audubon is synonymous with everything related to birds. Nearly 500 Audubon Societies and dozens of towns, neighbourhoods and landmarks in the USA bear his name. Are these honours deserved or appropriate? Probably not. Farb (1980) described him as a "habitual liar … a plagiarist … a poseur … and an irresponsible family man". In addition to these charges of serial dishonesty, Audubon also trafficked human skulls to assist Dr Samuel Morton's infamous ranking of human races by cranial capacity, now almost universally recognised as foundational to "scientific racism".

As ornithology grapples with distasteful eponyms and evaluates the moral character of those they honour, Audubon must not be given a free pass. His published works appear to be replete with lies, false data and (apparently deliberate) timeline distortions. Even his journals, which are supposedly contemporaneous sources, were manipulated by Audubon and his descendants. Yet, for more than a century, scholars have usually treated these materials as trustworthy primary sources. Halley aptly concludes with Audubon's own motto: "time will uncover the truth".

Original reference

Audubon’s Bird of Washington: unravelling the fraud that launched The birds of America. Halley, M. 2020. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 140(2): 110-141. DOI 10.25226/bboc.v140i2.2020.a3

References

Arthur, S. C. (1937). Audubon: an intimate life of the American woodsman. Harmanson, New Orleans.

Audubon, J. J. (1828). Notes on the Bird of Washington (Fálco Washingtoniàna), or Great American Sea Eagle. Mag nat hist & J zool, bot, min, geol meteor. 1: 115-120.

Dunlap, W. (1834). History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, vol 2. George P Scott and Co, New York.

Farb, P. (1980). After Audubon. A review of 'On the Road with John James Audubon ', by Mary Durant and Michael Harwood. In: Books in Review. Natural History, New York 89(5): 84-87 and Erratum 89(7): 77.

Halley, M. R. (2020). The theft of Morton's Hawk, now known as Harris’s Hawk. Cassinia 77: 27–33.

Halley, M. R. (2015). The Heart of Audubon: Five unpublished letters (1825-1830) reveal the ornithologist’s dream and how he (almost) achieved it.

Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life, accessed 20 April 2020. http://commonplace.online/article/the-heart-of-audubon/

Halley, M. R. (2018). Lost tales of American ornithology: Reuben Haines and the Canada Geese of Wyck (1818-1828). Cassinia 76: 52-63.

Morton, S. G. (1840). Catalogue of skulls of man, and the inferior animals, in the collection of Samuel George Morton, M. D., first edition. Turner and Fisher, Philadelphia, PA.

Woodman, N. (2016). Pranked by Audubon: Constantine S. Rafinesque’s description of John James Audubon's imaginary Kentucky mammals. Archives of Natural History 43: 95-108.