This article is based on a paper I wrote for British Birds which was published in January 2018. I am most grateful to the journal's Editor Roger Riddington for allowing me to reproduce parts of it, including some of the illustrations and photographs.

This was the first time an attempt had been made to establish the abundance and distribution of 'Polish' Mute Swans in Britain and Ireland, despite the fact that the first one was recognised in Staffordshire as long ago as 1686. However, it's perhaps not that surprising, as the first field guide to mention it (albeit briefly) was the Collins Pocket Guide to British Birds by Fitter and Richardson published in 1952.

A further 30 years were to pass before an illustration of one was to appear, in 1983 in The Shell Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland, showing a juvenile Polish swan with the all-white plumage, pale pinkish bill and just about the pale leg, compared with a normal one. My interest in Polish swans began in 1980 when I saw my first ones at Felbrigg, and subsequently Cley, both Norfolk, in 2008 and again at Felbrigg in 2014 and 2017.

With its very white plumage, rather than the usual greyish-brown, the Polish colour variant of Mute Swan is very noticeable in the chicks (Moss Taylor).

What is a Polish swan?

A Polish swan is a Mute Swan with a particular colour morph – it is white or virtually white from hatching and remains this colour for the rest of its life. However, when newly hatched and still in its primary down, it is not always easy to recognise, unless the bird is seen closely, as the body is actually a very pale cinnamon, while only the head and breast are pure white. This contrasts with a normal cygnet whose primary body down is pale greyish-brown.

But even at this early stage a Polish cygnet can be recognised by the characteristic pale pinkish-grey bill and paler legs and feet, compared with the grey of a normal cygnet. After a couple of weeks, Mute Swan cygnets moult into their secondary down, which in a Polish cygnet is pure white.

As they grow, the birds become easier to recognise compared with their normal-coloured siblings, and they remain different until they have all completed their first full moult. Once Mute Swans have reached adulthood after two years, the plumages of both a normal and a Polish swan are identical, as was shown by a pair at Cley. The cob was apparently normal (but see later) and the pen was Polish, as shown by the paler, pinkish-grey legs. But note that the bill of a Polish swan may be virtually indistinguishable from that of a normal adult.

This five-week-old Polish cygnet at Felbrigg, Norfolk, in 2017 is notably paler than its ‘normal’ siblings (Moss Taylor).

What's in a name?

Why is it called a Polish swan? To answer this question we need to go back to medieval times, when the tradition of keeping swans for the table first started. The Great Hospital in Bishop's Gate, Norwich, Norfolk, was founded in the Middle Ages as a home for the elderly – a function which it still fulfils today, although back then the residents were restricted to men of the church and the hospital was run by monks.

Behind the hospital is a swan pit, and although the current one was built in 1793, it was a replacement for a much earlier one that had been there since at least the 16th century. It was the last one in England in which Mute Swans were kept for the table. The practice came to an end during the Second World War – I have an old black-and-white postcard from the early 20th century showing swans in the pit – largely because of a shortage of grain with which to feed the birds. The pit still has water in it, but it has been empty of swans for around 75 years.

To increase the number of swans available for eating, London poulterers, from at least the early 1800s, imported Mute Swans from the Baltic region for sale as food and some of these produced white cygnets. In 1836, William Yarrell noticed some differences in the features of a pair of these imported swans that produced white cygnets, and he called them 'Polish Swans'. He could just as easily have called them Baltic Swans. He even suggested (incorrectly) that they were a separate species and gave them the scientific name Cygnus immutabilis, meaning 'the unchanging swan'.

Although this was not generally accepted by ornithologists of the day, Henry Stevenson was taken in and devoted no fewer than 10 pages to this 'new' species in his three-volume magnum opus The Birds of Norfolk, published in 1890.

The pair of Mute Swans at Cley, Norfolk, in 2015, with the carrier male on left and Polish female on right – note the pale leg (Moss Taylor).

The white down of the young cygnets also proved very popular in the clothing industry and in The Netherlands selective breeding of Polish swans was undertaken to obtain more Polish cygnets, thereby increasing the amount of white down that was available for use in making children's slippers, white being considered more attractive than grey.

Passing on

To understand how the Polish swan gene is passed from one generation to the next, we need to revisit our schooldays and the rules of Mendelian inheritance. In mammals the sex chromosomes are designated as X and Y. Females have two similar X chromosomes, which is known as being homozygous, while males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome, known as being heterozygous.

In birds the sex chromosomes are designated as W and Z, and it is the male that is homozygous with two Z chromosomes, while the female is heterozygous with one W chromosome and one Z chromosome. The melanin-producing gene that leads to the colour of a Mute Swan cygnet is located on the Z chromosome and it comes in two forms or alleles.

The one producing normal melanin – resulting in a normal-coloured cygnet – is dominant, while the one producing reduced melanin is recessive, meaning it is masked by the dominant allele. This is known as a sex-linked recessive gene. If the effect of the allele, producing reduced melanin, is not masked it results in the Polish morph.

As the Polish gene is located on the Z chromosome, a female Mute Swan which inherits the gene on her one and only Z chromosome will be a Polish swan, as it is unopposed. If a male Mute Swan possesses the gene on only one of his Z chromosomes, he will be a carrier, as the gene is recessive. He will have been a normal-coloured cygnet, although he will still be able to pass on the Polish gene.

In order for him to show the features of a Polish swan, he will need to have inherited the gene on both his Z chromosomes, one from each parent. By following all possible five combinations, using the rules of Mendelian inheritance, it can be shown that all Polish cygnets must have been fathered by a male that carries the recessive Polish allele on at least one of his Z chromosomes.

As an example let's take the pair at Cley, although the pen is a Polish swan, and the cob is apparently normal, he must in fact be carrying the Polish allele on one of his Z chromosomes, as the pair has produced some Polish cygnets.

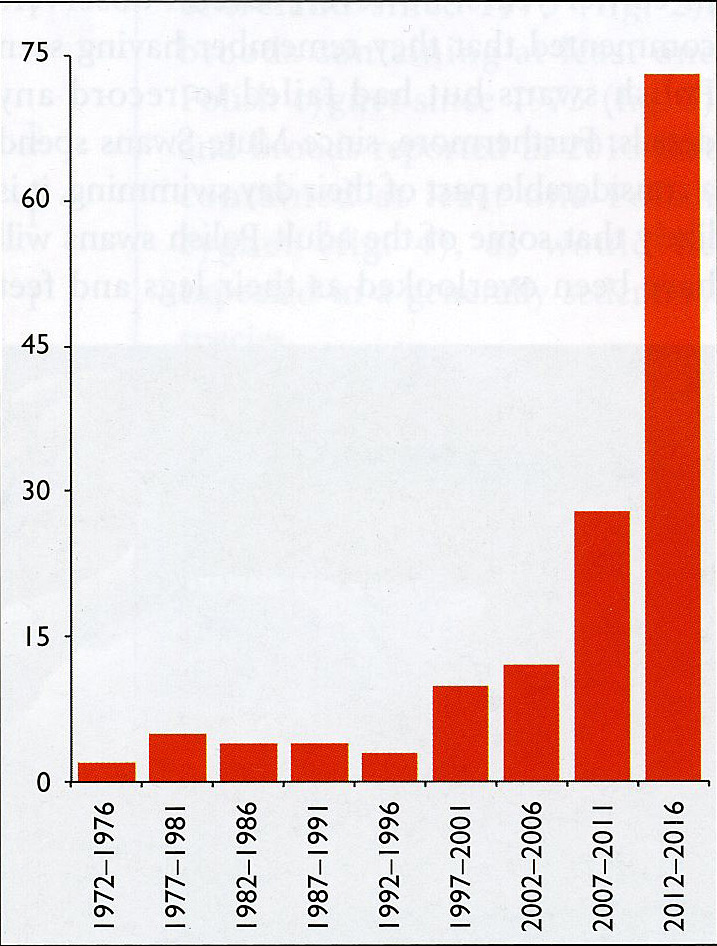

Number of broods of Mute Swans containing at least one Polish cygnet, reported in Britain or Ireland in each five-year period, 1972-2016.

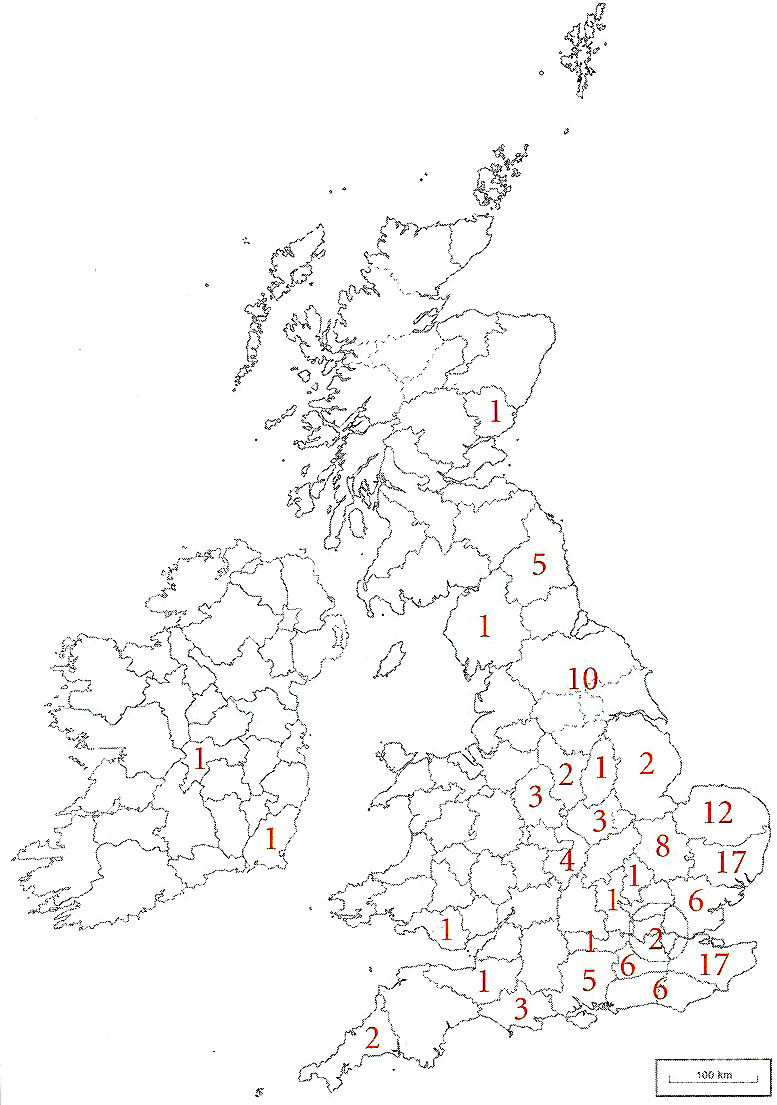

Number of localities in each county in which full-grown Polish swans of any age were recorded between 1973 and 1976.

Where does it occur?

As most county avifaunas fail to mention Polish swans, nor are they included in the majority of annual county bird reports, a literature search will provide few records. Therefore to attempt an assessment of the past and present abundance and distribution of Polish swans it was necessary to ask for observations from the readers of the birding magazines and journals. My initial approach was to write an article in the May 2015 edition of Birdwatch. This resulted in reports from seven localities since 1973 all of which were in south-east England.

The following year I made another appeal through British Birds, the RSPB's Nature's Home magazine, the British Trust for Ornithology newsletter and a selection of local bird club newsletters. This produced reports from 92 observers, including some in Belgium, France and North America. Colin Eaton read out my note in Nature's Home to his two sons aged three and six, and the next time they visited their local park in Basildon, they pointed out a Polish cygnet to their dad – a fine example of citizen science.

The resulting distribution maps show a clear bias towards counties along the eastern seaboard of England, with smaller numbers from the south coast and Midlands. The histogram of five-year periods demonstrates a dramatic increase in the number of records of Polish swans from 2012 to 2016, in line with the population growth of Mute Swans throughout the British Isles during the same period.

However, it’s not all good news for Polish swans, as cobs can look on their own Polish juveniles as rivals, in view of their all-white plumage compared with the normal-coloured juveniles, and there have been many recorded instances of cobs killing their own offspring, as well as simply driving them away. The all-white plumage also means that they lack the camouflage effect of the grey-brown plumage of normal cygnets, which is especially important when they are too young to fly and thus more vulnerable.

Finally the Cley Polish pen shows a deformed left leg, suggesting that it may have been broken in the past. Could the reduced melanin make the legs and feet more prone to injury, as it is known that the melanin-rich black tips of the flight feathers of Northern Gannets and many gulls confer strength to the tips of the wings and makes them less likely to be abraded? More research is needed!

- This feature was originally published in the June 2020 issue of Birdwatch magazine.