It would have been my 35th consecutive October visit to Scilly. A much anticipated, familiar and happy habit. By September we (Charles and I; we actually met on Scilly) very reluctantly decided to cancel our booking as quarantine on reaching the UK was not practical. We had continued coming to Scilly despite moving to Normandy 13 years ago, with the rationale being to keep up contacts with UK birders, see our friends, enjoy the beautiful place and sometimes be lucky enough see exciting species during the passage season.

On coming to France we settled down to atlasing, surveys and harrier protection. Indeed, in the field we had only bumped into anyone else birding on just three occasions, but one of these was very important; we met a top French lister at the coast one January. He was from the south and needed scoter for his year list! During our chat we discovered he had been to Scilly in 2007. Inevitably comparisons were made with Ouessant and his experiences of both. We kept in contact. When we cancelled Scilly our friend said "I can help you get to Ouessant". And he did. Suddenly, the thought of sitting at home throughout October had become less attractive than trying something new …

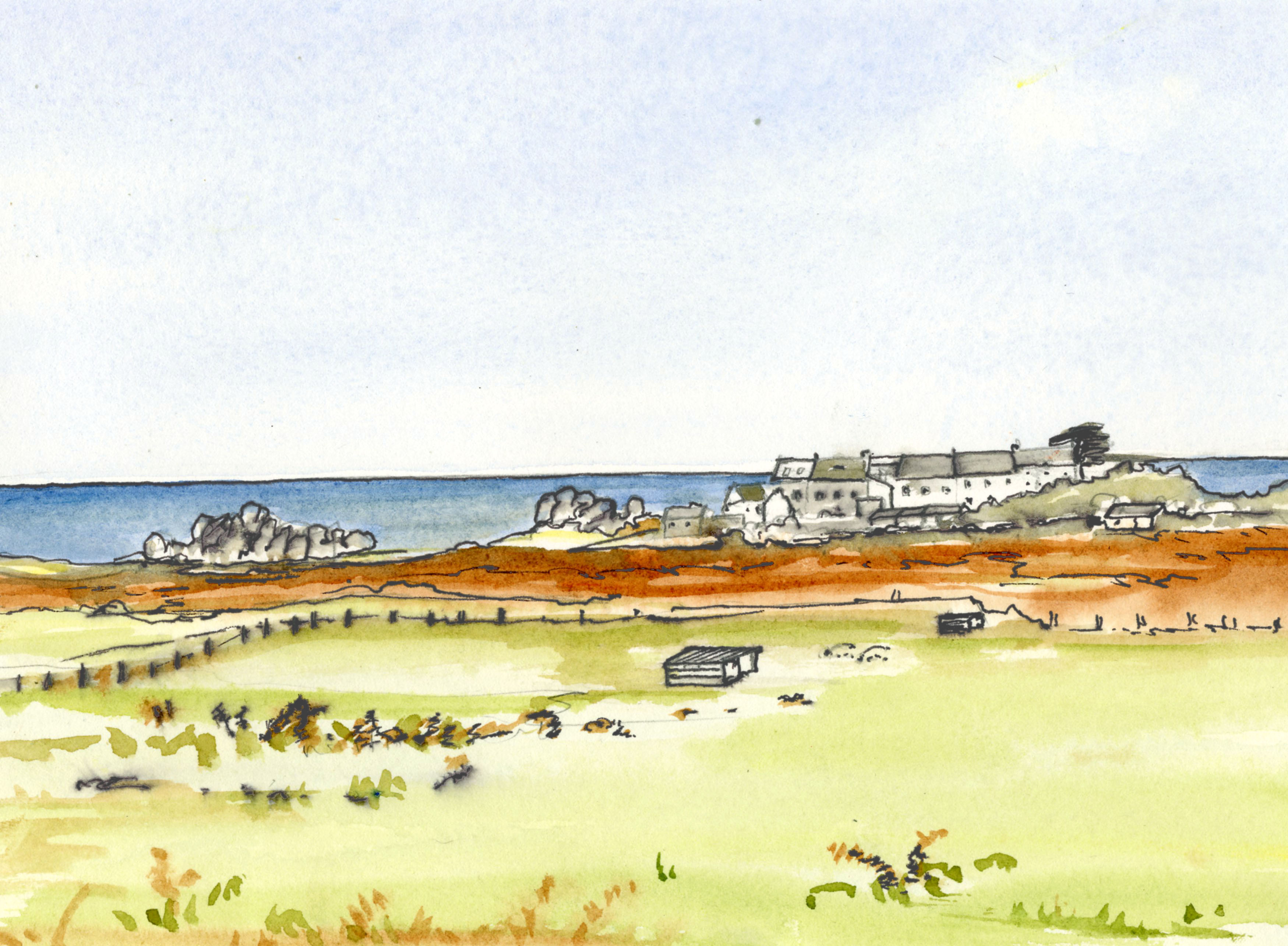

Ouessant sits at the south-western end of the English Channel and marks the north-westernmost point of France (Anna Hughes).

So, on a chilly and blustery October morning we were standing on a quay in western Brittany, waiting to board the daily ferry for Ouessant. I was a little nervous of not knowing French rare bird names and jargon, of the large island and of knowing only one other birder – our contact who had helped with planning the visit was already there. We knew nothing of transport, etiquette or the best areas to stay or look for birds.

Some of my fears were well founded. Ouessant is big; about 8 km long, 5 km wide, 38 km around the coast path and an awkward shape. It is also high. Unlike Scilly, it has cliffs, steep rocky coves and the sea is rarely at your eye level. The size is important: it needs serious means of transport other than by foot. The majority of birders are on the easily hired bikes which are the main way of getting about for visitors. It is however possible to rent a battered car for 40 euros a day from the one garage, but this is probably considered a bit dude-ish!

The habitat is very reminiscent of Scilly: worn granite, rough grass, gorse, heather and bracken. There are promising clumps of sallows in damp areas (known as stangs) and marshy wooded valleys. In fact, the whole island is like a very large version of Porthellick Down or Wingletang, with sallow clumps – some the size of Lower Moors – dotted every half a mile or so. Due to the many small groups of houses there are several tarmac roads, plus lots of tracks and a coastal path making access fairly easy.

However, Ouessant does lack bigger trees, the iconic pine belts of Scilly, small cultivated fields and pools for waders. Sheep graze freely. There does seem to be a lot of bird activity – excellent and varied vis-mig, Eurasian Bullfinches and (this year at least) hibernicus Coal Tits in privet hedges, lots of Common Starlings and plenty of pipits. A flock of Chough was a nice surprise but are in fact resident, as are Dartford Warblers. There is always something to look at. Scilly can be a lot quieter …

Ouessant attracts vagrants every year. This Swainson's Thrush was on the island in October 2019 (Adrian Jordi).

Apparently, there are no birders living full-time on Ouessant and the October influx to the island only began in 1985, with as few as nine birders. They are mostly focused young men and women and seemed very skilled and knowledgeable. This year was a record with some 100 birders coming from all over country and, given that it is a rare hobby in France, they form a close-knit temporary community. Over the week people did talk to us, often in English, and it helped greatly that on day five we found an Isabelline Wheatear and so achieved a little momentary fame! It was a new bird for quite a few.

Rather than WhatsApp or radios they use Telegram (a cloud-based instant messaging software) and keep it strictly to the rarities. This meant we were still not totally sure what was 'good' or not. The regular rarities and semi-rarities though were very familiar: Yellow-browed, Dusky, Barred and Radde's Warblers, Red-breasted Flycatcher, Richard's and Olive-backed Pipits, Rosy Starling, Greater Short-toed Lark, Little, Lapland and Snow Buntings, Eurasian Wryneck, and Short eared Owl.

Seawatching in the right winds is very productive. Sabine's Gull, Long-tailed Skua, Great and Balearic Shearwaters and Little Auk were seen a few times. While we were there the main rarity was a long-staying Spotless Starling – only the second for the island and extremely notable this far north. Also in October there was a Spotted Sandpiper, an exciting mystery nightjar species, two Eastern Yellow Wagtails and a Corncrake.

In all, it was a mixed experience. Travel and self-catering accommodation were good and a lot cheaper than Scilly. We were very welcome but still outsiders, knowing almost no names. Instead, I asked people where they came from and that worked until we had collected three separate "man from Orleans". The main issue for us was the sheer size and potential of the island; it's so difficult to cover it well and I missed the connection with sea. On Scilly, the inter-island boating is an everyday affair and the pelagics on the Sapphire are among some of my all-time favourite days.

The habitat is reminiscent of Scilly: worn granite, rough grass, gorse, heather and bracken, as depicted by Anna in this painting (Anna Hughes).

Would we go again? Yes, for the constant stream of really good birds to look at and for the keen, friendly birders. Yes also for the great crêperie in town and the lovely bit of Finistere coast to explore on our way there and back. On the other hand, no, for the reason that without a young person's mobility it's too large to cover easily – we'd need a few days in that old rust bucket of a car! We did the right thing to give it a try and perversely have to thank the virus to have opened up this opportunity.