It's 4 am in the cloudforests of Mount Wilhelm, Papua New Guinea. A cold fog has condensed on my sleeping bag and water is starting to seep in. Before I get too soggy, I pull myself out and start kitting up. Strapping on a headtorch and filling a drybag with several cameras, an assortment of lenses, a sound recorder, two boiled eggs and a flask of jet-black coffee I head into the cloudforest on my own.

It's a pretty savage start to the day, but I'm buoyed up by my mission. After trekking for just shy of an hour I reach a tiny palm bivouac I had weaved with the brilliant ex-bird-of-paradise-hunting local villagers the day before. This one-person shelter, just big enough for me, had to be constructed out of the right species of palm, apparently, or the performer I was here for wouldn't show up.

The hide has one tiny opening in the palm fronds that allows a super low-angle, close-up view of a doughnut of vegetation 30 cm high and 1.5 m across, with a spire rising 1.5 m from its centre. The doughnut is a thick ring of moss and branches, while the central maypole is a tower of sticks that looks like the result of an obsessive round of pick-up-sticks. It is utterly bizarre and has a Blair Witch Project feel about it. In fact, it's possibly the most architecturally impressive structure made by any single animal – the bower of a MacGregor's Bowerbird. I'm trying to 'work' hides across multiple bowers to find the best angles for our remote cameras and long-lens cameraman.

This spectacular construction, like something from a cult horror film, is made by a male MacGregor's Bowerbird.

Several hours go by in darkness. I start my day list as a Papuan Eagle calls single, piercing notes nearby, while a Spotted Jewel-babbler blunders into the hide and almost over my feet. At 6.06 am, a Mistle Thrush-sized bird drops into the doughnut and blasts me with a chorus of mimicry, giving a perfect run-down of the local honeyeaters, fantails, kingfishers and parrots. I peer out at the bowerbird, which is now carefully attaching baubles of sticky tree sap to the lower branches of his maypole, just 2 m from me. Unlike other bowerbirds, which tend towards an obsession for colour and 'bling', this species has a palette for beige, with a particular penchant for brown balls of rotting goo and dead flowers.

When a second bird of similar size drops into the doughnut, the male bowerbird goes into overdrive – a female is here! She's intrigued by his impressionist skills and makes a move towards him, but he skips behind the maypole and peers back at her as if playing hard to get. Then, for an extremely entertaining two minutes of foreplay, the two chase each other in little laps around the doughnut, with the male stopping occasionally to sway from side to side while an orange blaze of plumes fans out from the top of his head.

An orange blaze of plumes adorns the male MacGregor's Bowerbird's crown.

Then, mid-display, to my horror and disbelief (in such a remote part of the forest), I hear what I can only comprehend to be the grunting of a pig. The nearest village is home to free-roaming pigs that could, I suppose, have entered the forest. As the grunts get louder my heart sinks – it must be headed straight for the bower. Next comes the unmistakable increasing sound of children shouting – also heading this way!

The pig grunts quieten, and I gratefully assume that the kids have scared the animal off. However, when the chatting and howling of the children is so loud it sounds like they should be on the bower itself, it hits me – it's the bird! Female bowerbirds are impressed by males that perform with the biggest range of sounds, be it a pig grunt or nursery rhyme. In a devoted (and creepy) quest for an ever-better repertoire, this male MacGregor's has gone to the local village and listened in at playtime …

A male MacGregor's Bowerbird in action.

For Dancing with the Birds, we wanted to capture the most intimate view of our bird-of-paradise, bowerbird and manakin performers to be shown on screen. This took a lot of trial and error, time, patience, pushing for different camera angles and trying to get closer than ever. One cameraman, Sam Stewart, sat in a tiny palm hide looking at an empty branch in the dark for the best part of two months.

He was waiting for a King of Saxony Bird-of-paradise, which has the world's longest head feathers, to drop down on to his chosen display vine in New Guinea's Central Highlands. The problem was the bird would use four or five different vines in different parts of the forest, and it was pot luck whether he would choose the vine Sam was on, on that particular morning. After more than 40 empty, lonely mornings of nothing, the King showed himself to Sam and he managed to capture the clearest portrait yet of this spectacular BOP's entertaining display.

It took well over a month for the King of Saxony Bird-of-paradise to finally give himself up, but it was well worth the wait.

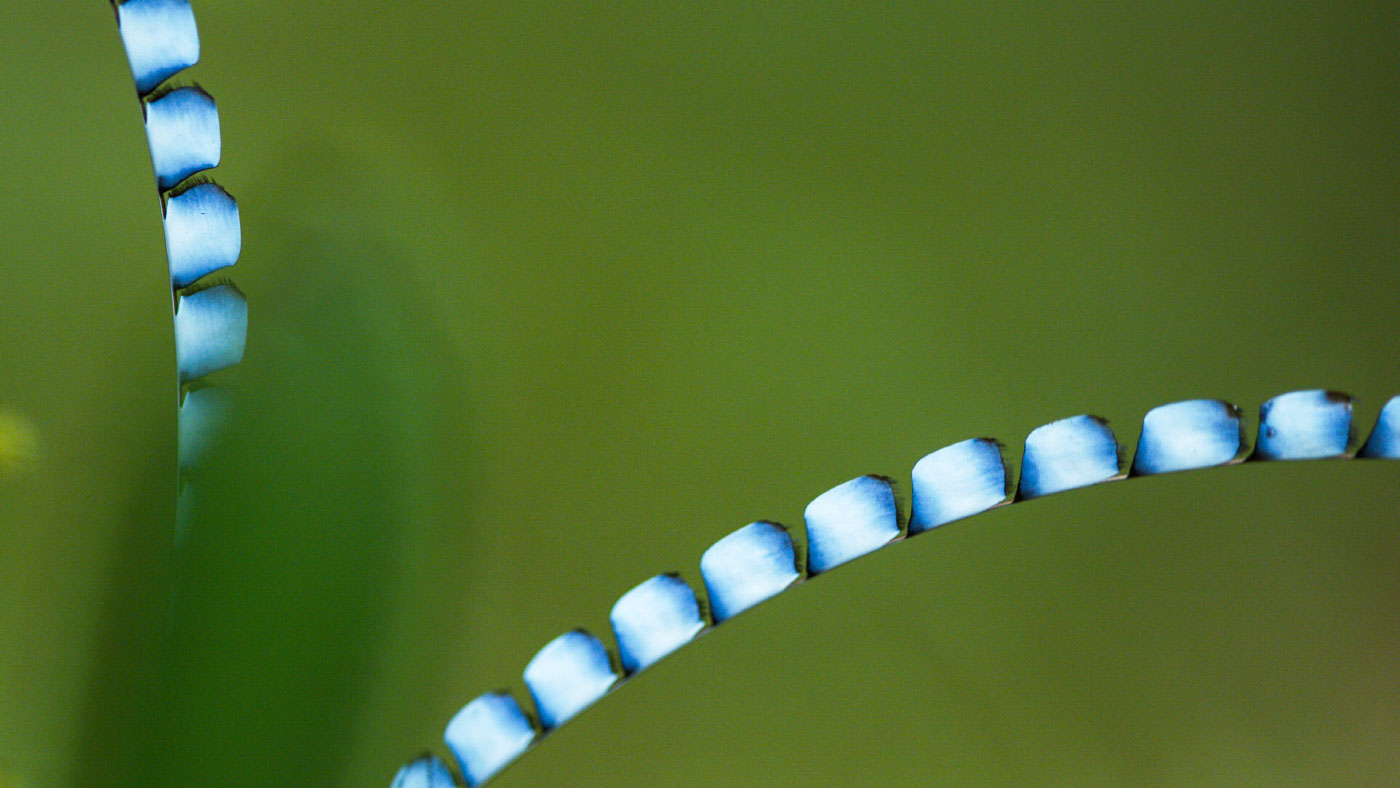

The King of Saxony's head feathers aren't only appealing to females of the same species. One bowerbird has particularly fanciful taste. The large, rare and little-known Archbold's Bowerbird builds a vast, suspended chandelier of a bower, full of dangling vines and orchids, and garnishes it with a carpet of snail shells and several King of Saxony head feathers. Our local team found one bower after many months of searching. Bowerbirds are generally far more sensitive to changes in their immediate surroundings than birds-of-paradise, and perhaps none more so than this species.

When seen up close, it's easy to understand why a male King of Saxony Bird-of-paradise's unique head ;feathers prove so appealing to an Archbold's Bowerbird.

So, to position myself close to the action would require a new level of camouflage. The local villagers and I found a hollow under a tree root right next to the bower and built a coffin-like cocoon of moss around my body, with a tiny hole for one eye to peek through. It all felt worth it when, the following morning, the massive bowerbird appeared, statuesque on his bower, with a long, shaggy yellow crest, just a metre in front of me. In the end it was just too difficult to film at the bower, but I'll always treasure that memory.

Toby's makeshift 'hide' involved being cocooned in moss and leaf litter in order to see and film Archbold's Bowerbird.

We made some surprising finds while filming in remote New Guinea. I was with cameramen Tim Laman and Ed Scholes filming Western Parotia's brilliant ballerina display, when Ed noticed bird poo on a rotting log where a tree had fallen, creating a small opening in the canopy. Ed correctly deduced it to be the faeces of a Superb Bird-of-paradise, only ever filmed once (15 years ago, for BBC's Planet Earth). We set up a palm hide next to the log and, despite the bird being a nightmarishly unpredictable performer (involving empty weeks of us staring at a vacant log), Tim captured the clearest footage of a Superb Bird-of-paradise's performance to date.

Looking at the imagery, listening to the calls and watching the dance, this Superb was clearly very different. Unlike the nominate species with its bounce-and-click display, this bird hovered sideways in a single, smooth, tango-like move. Its plumes were a crescent shape, unlike the oval disc shape of the nominate bird. The female had a very different face pattern, and the male's calls were distinct too. This was the first clear portrait of what transpired to be a new species, Vogelkop Superb Bird-of-paradise, or Crescent-caped Lophorina as it is now known.

Tim Laman's footage of a 'Superb Bird-of-paradise' in the Vogelkop Mountains helped to build the case for this distinctive taxon to be recognised as a separate species. Read more about this discovery here.