The coasts of Britain and Ireland are world renowned for holding spectacular seabird colonies in the summer months. However, the populations of many of our most beloved species have shown worrying declines in recent years, as revealed by long-term studies conducted by scientists from the RSPB, BTO, JNCC and others.

While breeding sites are invariably well monitored, very little is actually known about seabirds' lives when they are at sea. Given that this is where they spend most of their time, it is clear that we are still a long way from understanding the complex and intricate lives of many species that we consider familiar.

Breeding sites are generally well protected — many are nature reserves — but feeding grounds remain largely unguarded. The list of reasons for observed seabird declines is long and varied, but one of the critical factors appears to be that adults are simply unable to find enough food in terms of quantity, quality or both, at crucial times during the breeding season. This leads to starving chicks and ultimately failed breeding attempts.

The availability and presence of adequate feeding grounds is therefore of paramount importance to maintaining seabird populations. The need for marine 'nature reserves' seems obvious but our seas are largely unregulated domains at present, offering little or no respite for our marine life. This is particularly stark when considering that all British seabirds are either Amber- or Red-listed, meaning all are of conservation concern.

The European Commission's Birds Directive requires the installation of a European co-ordinated network of protected areas. Special Protection Areas (SPAs) are well established on land in the UK but, while marine areas are afforded some protection, just four wholly marine (i.e. offshore) SPAs exist in UK waters.

The good news is that this paucity is recognised and work is well underway to establish a suite of marine SPAs. Proposed Special Protection Areas (pSPAs) are currently being considered in English and Scottish waters, the latter of which are currently open to public consultation.

Recognising the perilous situation that our breeding seabirds find themselves in, conservation NGOs such as the RSPB continue to implement projects to better understand their lives and, in turn, to identify which aspects require specific focus for protection. Given the importance of feeding grounds to seabirds in the breeding season, much effort is now being invested in studying where birds from various colonies are travelling to feed. In recent years we have witnessed the extraordinary rise of GPS tags (geolocators) as game-changing tools in the understanding of birds' movements, and their importance in determining what seabirds are up to at sea cannot be highlighted enough.

Populations of Atlantic Puffins are falling across the species' range (Photo: Josh Jones)

In late June I was invited up to Fair Isle, Shetland, by the RSPB in order to observe their latest project, focusing on arguably our best-loved and most charismatic breeding seabird: Atlantic Puffin. Though still fairly common, it is well known that some British populations of Puffin have suffered significant declines, as they have in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Norway, and the species was recently 'upgraded' to Vulnerable on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species.

The aim of this project was to gather adequate data to figure out the feeding patterns of Fair Isle's Puffins — where (and how far) they are going, how long they are spending at sea, how regularly they are making trips away from their burrows, what they are feeding their chicks with, and so on. This data is potentially very important in the establishment of SPAs in Scottish waters and is also crucial for understanding where is and where isn't suitable for offshore developments, such as windfarms.

To achieve this, scientists caught 30 adult Puffins and fitted each with a GPS tag (a similar number were also fitted with tags on Foula in early July) and I was fortunate enough to be on Fair Isle while this was taking place. Puffins are caught using mist nets erected near their burrows — they are not removed from the burrows for tagging as this causes the adults excessive stress and may result in them abandoning the nest. Indeed, previous studies have caught adults in the burrows and this appears to have had an adverse effect on the regularity of feeding trips for the chicks (which also leads to misrepresentative and skewed data for science).

The species tends to be quite sensitive to any sort of disturbance, so the catching process is executed quickly and quietly to minimise the strain on each bird. Each bird is first measured, weighed and aged. The latter is judged by the number of bill grooves an individual bird shows — two grooves means a Puffin is five years old, three equates to an age of at least seven. The tags are then attached to the birds' backs before each individual is sprayed with blue dye in a unique shape to make it more readily identifiable. The birds are then released.

Setting up mist nets to catch Puffins returning to their burrows at Buness, Fair Isle (Photo: Josh Jones)

The birds were caught as they returned to their burrows with fish, and so their catch is bagged up for analysis — number of fish, species caught and size of individual prey items are analysed to give an idea of how successful forays are proving. Sand eels are the preferred prey ("a kind of Puffin superfood", says the RSPB's Dr Ellie Owen) but both rockling and Gadoids (cods) also feature regularly among the catches.

A single catch from an adult Puffin, consisting of sand eels, rockling and Gadoids. Catch varied individually, with many containing a considerably higher percentage of the former fish, which is the favoured food for Puffins. (Photo: Josh Jones)

Thankfully the tags, which weigh just 7.5g and cost £525 apiece, do not need to be retrieved to download their data — a win-win situation as it means less stress for the birds and less work for the scientists. Each time a tagged Puffin returns to its burrow it finds itself within range of a receiver, situated about a kilometre away from the tagging locations, which picks up the GPS data that the tags have obtained. The GPS data is then downloaded manually from the receiver using a laptop.

A tag is affixed to an adult Puffin's back; great care is taken to minimise disturbance and stress to the birds during the process.

(Photo: Josh Jones)

The tags' batteries last around five days, which is enough to ensure that a good amount of data can be obtained from each bird. After time the adhesive used to attach the tags wears away, meaning they simply drop off. To lose tags costing in excess of £500 each may sound wasteful but, in light of other methods failing, this is an all-out attempt by the RSPB to provide accurate data without affecting the birds at what is an important stage in the species' conservation.

Early results suggest that this experimental project has thankfully been a success. The method used was 'new' for the species and there was always an underlying risk that it might not produce any valuable data. Dr Owen was therefore very pleased to report that 57 of the 60 Puffins tagged on Fair Isle and Foula provided data and motion-sensitive cameras, placed near the birds' burrows, will give data to show whether or not there were any effects on the Puffins' behaviour resulting from the tagging process.

While it's still too early to say exactly what the data reveals in depth, Dr Owen commented: "Firstly, we found that Puffins were making shorter trips around the colony but also longer trips much further away — these trips were far longer than any that have previously been recorded by direct means [in the species] so we might need to do a bit of re-writing of the Puffin foraging ecology 'book'. It's likely that the longer trips are Puffins foraging for food to feed themselves, perhaps going further to find particularly abundant and predictable prey, and the shorter trips might be when out gathering fish to feed to their chicks."

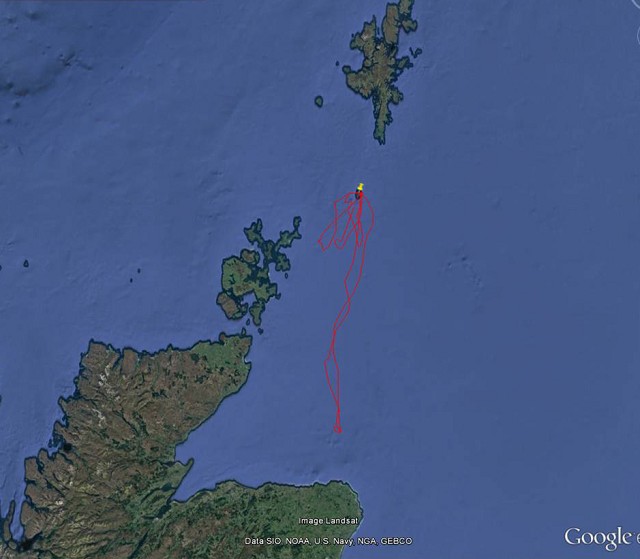

This initial plot of GPS data from a single tag reveals that Puffins are travelling much further on feeding forays than scientists previously thought. As well as completing multiple shorter journeys, this particular bird travelled as far south as the Moray Firth off North Aberdeenshire on a 24-hour trip away from its burrow in late June.

The success of this method and the understanding it gives rise to cannot come soon enough for a species that is really struggling in some areas. The subsequent Foula project appears to have gone equally well, but Dr Owen added that colonies on that island are "declining at a steep rate and the birds were clearly struggling to find food, with some Puffin chicks leaving burrows before they were old enough because they were not being fed — it's a sad picture."

Dr Owen and her team hope that the tracking data will be one big step towards decoding the mystery of what is going wrong for Puffins not only across Shetland, but Britain as a whole — sentiments that will no doubt be echoed by all wildlife enthusiasts for one of our most recognisable, charming and beautiful species.

Atlantic Puffin, Fair Isle, June 2016 (Photo: Josh Jones)

For more information on the RSPB's science and conservation projects, please visit: www.rspb.org.uk/science

You can follow @RSPBScience on Twitter.

Special thanks must go to David Parnaby and the team at Fair Isle Bird Observatory for their warm hospitality during the trip.