The relatively short history of Ring-billed Gull on the European side of the Atlantic makes for a fascinating story, particularly so in Britain and Ireland, where it has experienced marked oscillations in its fortunes since it was first definitively recorded 46 years ago.

Though very much a North American species in terms of its breeding and wintering ranges, Ring-billed Gull is now a familiar and expected bird on this side of the Atlantic and has been recorded in every month of the year, albeit with a clear peak in winter and early spring, when wintering birds are bolstered by northbound migrants. As with other Nearctic species, the western periphery of Europe fares best for this charming, medium-sized gull.

Adult Ring-billed Gull is both attractive and distinctive, and encountering one on 'this' side of the Atlantic is always a pleasure (Joe Graham).

Although documented in the likes of the Azores, Spain and Germany many years beforehand, it was first recorded in Britain as recently as 1973, when Rob Hume identified a single bird on the beach among Common Gulls at Blackpill, Swansea, Glamorgan, on 14 March.

This proved to be the catalyst to a surge of reports that translated into one of the most rapid status changes ever witnessed among any bird species recorded in our isles. Hume and his fellow Swansea University students documented a further 10 individuals at Blackpill by the end of 1975. The first Irish record came in 1979 from Belmullet, Co Mayo. By the end of 1980, 44 individuals had been noted in 11 British and Irish counties.

Such an exponential rise in status was no doubt in part due to a rapidly growing awareness of both the scope for its occurrence on our shores and the field identification characteristics. Increasing numbers of newly informed birders began to pick up the species in their local gull flocks. However, even accounting for this, it does appear that a huge and genuine influx did occur in 1981, when 65 per cent of the 55 birds recorded across Britain and Ireland involved first-winters. The startling numbers continued in subsequent years: in 1982 there were 75 and in 1983 the figure rose again, to 84, although in both years there was a noticeable drop in the relative proportion of first-year birds.

The aggressive upward trend meant that, throughout the '80s and '90s, Ring-billed Gull was an almost expected feature of winter birding, even in eastern areas of Britain, where regularly returning, site-reliable adults could be depended on year after year, while good numbers of 'new' first-winter birds continued to be discovered. Some speculated that the species might even colonise, should its apparent rate of expansion be maintained. Indeed, the documentation of adults frequenting Common Gull colonies, as well as apparent hybrids with that species, suggested that Ring-billed Gull was perhaps beginning to establish a toehold in Europe.

In addition to wintering birds, Ring-billed Gull became an expected spring passage migrant, often among Common Gulls, at favoured west-coast sites throughout the '90s. At this time it increased in regularity at Seaforth Docks, Lancs, where this second-summer was photographed in May 2007, but it has gone rare again there in recent years (Steve Young).

The tide turns

However, roughly at the turn of the century, an unforeseen twist began to play out. Over the past 15 years, Ring-billed Gull numbers have gradually dwindled once more – across both Britain and Ireland.

As regularly returning, old-age adults have slowly disappeared from traditional British haunts – including famous birds at Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, Isle of Dogs, London, and Gosport, Hampshire, all of which padded out year lists time and time again – the paucity of new arrivals has been exposed. Precious few first-winters are now found each winter in Britain, with little or none of these returning year on year, exacerbating the encroaching drought as reliable adults die out. As such, annual totals for the species continue to gradually fall away.

'Rossi' the Ring-billed Gull wintered at Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, for 12 consecutive years. This image was taken in January 2009; it was last seen in March 2011 (Steve Young).

This slump would certainly appear to be genuine, for observer coverage – and competence of said observers – has never been higher than it is today. Sites such as Hayle Estuary and Helston Boating Lake, Cornwall, which in times gone by might have attracted multiple individuals every winter, now struggle to record the species on an annual basis despite being watched daily. Blackpill – the site where the story began – was still attracting ones and twos in the early 2000s, with a peak of three on 26 April 2002, but since 2004 records have become sporadic at best. Although coverage of gull flocks in the area has apparently diminished in recent years, that alone cannot fully explain the sudden series of blank years, punctuated only by the appearance of two adults there in spring 2014 – these also representing the last record from this famous stretch of coastline.

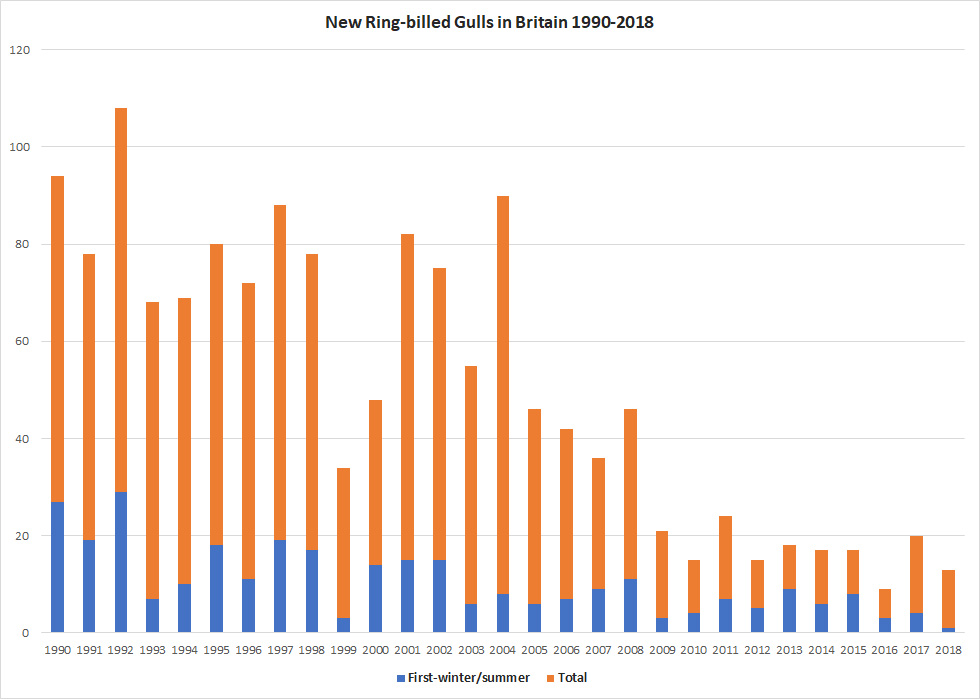

Overall statistics seem to back this up, too. In 2016, just nine new birds were found across Britain, and only three of these were first-winters – this the lowest total of new arrivals since 1979. Although BirdGuides data suggests a slight rebound from this low in 2017, with 20 new birds that year, the tally decreased again to 13 new birds in 2018, including just a single new first-winter. The graph below vividly illustrates not only the decrease in the number of new birds occurring annually each year in Britain, but also the consistently low number of first-winter birds since 2003.

Graph depicting total number of new Ring-billed Gulls seen per year in Britain from 1990-2018 (orange), including number of new first-winter birds (blue). Data for 1990-2016 adapted from the annual British Birds reports on scarce migrant birds in Britain; data for 2017-18 from the BirdGuides.com sightings database.

The downturn appears similar – if less terminal – just across the Irish Sea, where there too has been a decline in the number of young birds arriving each winter, combined with a gradual loss of long-serving adult birds. Gone are the heady days of the '80s and '90s, when numbers could approach and even enter double figures at favoured sites such as Nimmo's Pier, Co Galway, Blennerville/Tralee, Co Kerry, and in spring, Sandymount Strand, Co Dublin. A count of 13 was made at Blennerville on 9 April 1986 and 15 individuals were seen there on 27-28 March 1994, with 14 also noted at Sandymount in the mid-1990s. The peak day count at Nimmo's Pier came in spring 1999, when nine were present. The following winter produced at least 10 birds there.

Since then, though, things have gone awry for this previously numerous winter fixture that, at one point, looked like a likely colonist. In fact, Nimmo's, which has always been viewed as a hotbed for Ring-billed Gull action, recorded just a single adult in the entirety of winter 2018-19 – the result of a gradual decline in new birds arriving there over the past 15 years. However, as evidenced by the five seen in Tralee on 17 March 2019, peak spring passage in March and early April still has the potential to produce respectable counts on occasion, while ones and twos continue to occur at other regular sites, such as in Limerick and Cork cities.

A decreasing number of first-winter Ring-billed Gulls have been found in Britain and Ireland over the past decade. With fewer younger birds replacing the diminishing stock of old-age adults, its overall frequency has declined. This youngster was at Bantry, Co Cork, in February 2012 (Richard Bonser).

Wider reflections

Looking further afield, the overall negative trend appears to be reflected across much of Atlantic-coast Europe. France experienced a rapid rise in numbers of Ring-billed Gull records throughout the 1980s, similar to that observed in Britain and Ireland, with a growing quantity of regularly returning birds taking up residence each winter along the Atlantic coast. It was removed from the list of species assessed by the French Rarities Committee on 1 January 2006, but since then it has become increasingly rare again, with a diminishing number of first-winter birds being found and long-lived adults slowly disappearing.

Arcachon Bay – the traditional stronghold for the species in France – no longer appears to attract new, young individuals, this very much a reflection of what has been observed at hot-spots across Britain and Ireland. In recent years up to three individuals have been seen here, compared to at least five or six birds a few years previous and double-figure counts in the mid-2000s. An average of just 15 have been seen across the whole of France in recent winters.

Arcachon Bay, on France's west coast, has traditionally produced the highest single-site counts of the species in the country, with double figures often present in the early 2000s. However, just three have been seen there this winter, including this pair of adults photographed on 29 March 2019 (Loïc Le Comte).

The situation is similar in Spain, with the country's north coast hosting large numbers of the species throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, with counts sometimes approaching 20 individuals at sites such as Gijón, Asturias. Some of the Gijón birds were colour ringed, with these returning in subsequent years. However, since then there has been a steady decline across Spain, with just a handful of individuals seen in winter 2018-19. This is exemplified by counts from Asturias: 23 birds were seen in 1997, decling to eight in 2012, 10 in 2013 and just a single bird in the region so far in 2019.

Given its geographical position, it is no great surprise that the Azores has traditionally produced the highest counts of Ring-billed Gull within the Western Palearctic. While a small number of new vagrants appears across the archipelago each year, Terceira Island is unique in that it has traditionally attracted a sizeable wintering flock. Data prior to the turn of the century is scant, although maximum counts since then include 56 in February 2001, 33 in 2003, 25 in 2004, 46 in 2005 and 26 in 2007.

What is telling is the gradual but nonetheless noticeable drop from 2005 onward. While the flock still regularly peaked in the low twenties in the late 2000s and early 2010s (for example, 23 on 22 February 2011), such figures have grown increasingly scarce as the 2010s have progressed. Twenty-two were tallied on 16 February 2014, but nothing has come close since. Winter 2017-18 produced a maximum of 12 birds, including just two first-winters (the rest adults), with early 2019 counts peaking at 14. Therefore, though a sizeable wintering population still remains, the story is a familiar one to that encountered across mainland Europe – a diminishing number of individuals and an ageing population among those returning birds.

The wintering flock of Ring-billed Gulls on Terceira, Azores, has dwindled from over 50 birds to just 14 over the past 15 years. Here, nine are shown (with a single adult Common Gull; far right, obscured) at Praia da Vitória beach, where the birds gather daily in an afternoon roost (Josh Jones).

Drivers of the decline

It's likely that no single reason can be pin-pointed as the cause of the observed decline across Europe in recent years. However, looking at population trends in North America over the past five decades reveals strong clues as what might have driven the explosion of records in the 1980s and its subsequent slump.

Taking advantage of man-made opportunities – such as food waste providing improved feeding – Ring-billed Gull experienced a spectacularly rapid population increase in North America from the 1970s. In the Great Lakes, numbers rose from 305,790 nests in 1976-80 to a peak of 718,887 nests in 1989-90. The correlation between this explosion and the rise in European occurrences is clearly significant. What's more, the subsequent regression of the Great Lakes population to 652,664 nests in 1997-2000 and then 585,984 nests in 2007-09 may also go some way to explaining what took the wind out of the sails of the apparent expansion into Europe at the turn of the century.

Localised population declines are likely one driver of the downturn in Ring-billed Gull records in Europe over the past decade (Geoff Campbell).

While estimates are not freely available for other populations of the species, the Status of Birds in Canada 2014 report states that "its breeding range continues to expand into northern Canada". Therefore, if the species is still increasing in some areas, the downturn in Europe cannot simply be attributed to population trends alone.

Quite what else is at play is unclear. It's perhaps not a coincidence that there has been a similar decrease in the regularity of American Herring Gull in Britain and Ireland over the past 15 years, despite identification awareness now at unprecedented levels – meaning vagrants have never been more likely to be picked up than now. Presumably variations in annual weather events – be it mid-winter freezes or autumn storms – play their part, but North American regions are still regularly exposed to 'polar vortex' conditions (which could induce mass displacement events) in winter, and North Atlantic storm activity, which is generally seen as a pre-requisite to transatlantic vagrancy among North American birds, has not waned in recent times.

Uncertain future

From the available data it appears that Ring-billed Gull reached a peak in Europe during the 1990s, following a spectacular upsurge in records from the early 1980s onward as identification awareness grew in tandem with repeated large influxes. At or around the turn of the century, the bubble burst and the upward trend levelled out, with numbers remaining high but not increasing into the early 2000s, before gradually starting to fall away. While the reason for this is not obvious, it may well be linked to localised population declines in North America, with fewer young birds being recruited to flocks wintering in Europe. Over time, the decrease in young birds on this side of the Atlantic created an ageing population which, without further recruitments, has begun to dwindle as reliable, old-aged adults gradually die off and are not replaced. Decreasing counts from France, Spain and the Azores seem to confirm that this is a widespread decline rather than a phenomenon limited to Britain and Ireland.

Keith Vinicombe wrote in his 1985 British Birds paper that "there can be little doubt that Ring-billed Gull will never return to its former extreme rarity status", but while the species is still a long way off being an 'extreme' rarity, it now teeters on the very edge of becoming officially rare once more. Unless another sizeable influx occurs in the near future, it could well be that British birders may once more have to put pen to paper and submit their records of this species to the British Birds Rarities Committee – something that would have seemed scarcely believable even a decade ago. From a birders' perspective, let's hope it never gets to that – another healthy arrival of this undeniably engaging species in coming winters would certainly be welcomed.

Could Ring-billed Gull be heading for rarity status once more, or will it bounce back after a lean decade? (Josh Jones).

References

Birds of North America. Ring-billed Gull [Online]. [29 March 2019]. Available from: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/ribgul/introduction

Government of Canada. Status of Birds in Canada 2014: Ring-billed Gull [Online]. [29 March 2019]. Available from: https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2014

Morris, R D, Weseloh, D V, Wires, L R, Pekarik, C, Cuthbert, F J & D J Moore. 2011. Population Trends of Ring-billed Gulls Breeding on the North American Great Lakes, 1976 to 2009. Waterbirds 34(2): 202-212

Vinicombe, K E. 1985. Ring-billed Gulls in Britain and Ireland. British Birds 78: 327-337.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Steve White and British Birds for providing Ring-billed Gull data from 1990-2016. Thanks must also go to Hugo Touzé, Niall Keogh, Ed Carty, Dermot Breen, Daniel López Velasco and Peter Alfrey for their contributions and expertise.