Grey-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus cirrocephalus) is a patchily distributed resident across much of sub-Saharan Africa (C. c. poiocephalus) and parts of eastern South America (C c cirrocephalus), the latter nominate subspecies being colloquially known as 'Grey-hooded Gull'. Slightly larger and bulkier than the familiar Black-headed Gull (C ridibundus), adults show a distinctive pale grey hood in breeding plumage which, alongside a pale iris, gives a particularly distinct facial impression. In non-breeding plumage, adults assume a typical but variable small hooded gull head pattern, while the deep red bill pales but remains dark-tipped. In flight, adults show a distinctive black-and-white wing pattern, with white mirrors on p9 and p10 contrasting with a largely black wing-tip, which clearly differentiates it from Black-headed Gull. Upperparts are generally a slightly darker grey than in Black-headed Gull.

Identification is a little more subtle in juvenile and first-winter plumages; upperwing pattern is similar to Black-headed Gull but a little more contrasting, with better-defined white on the outer primaries and an entire black wing-tip. The pale iris is generally not obtained until at least the second winter. Nominate cirrocephalus of South America averages slightly larger than African poiocephalus, with slightly paler upperparts and larger mirrors on p9-p10 in adult birds. As one might expect for an equatorial species breeding at differing times in both hemispheres, moult timing is highly variable – so much so that it can vary from colony to colony.

Breeding-plumaged adult Grey-headed Gull in The Gambia (Sean Johnston)

The South American population breeds almost entirely within the southern hemisphere, primarily in Argentina but also along the Pacific coastline of Peru, with smaller numbers in Brazil and Uruguay. The African population is focused primarily within the tropics, with the largest colonies known from Kenya, Uganda and Senegambia, though it has steadily increased in South Africa and a very small population exists as far north as 20°N in Mauritania. Despite an African range centred around the equator, the species does appear to show an established propensity for roving well north of its expected range. This article will attempt to establish the history and pattern of this dispersal into Europe, and demonstrate the feasibility of the species as a potential vagrant to Britain.

Grey-headed Gull in the Western Palearctic

Within the Western Palearctic, the species occurs regularly only in coastal Mauritania, on the extreme fringe of the region. There, a small and declining breeding population of 10-50 pairs and some 50-200 wintering individuals can be found in the Banc d'Arguin National Park (Isenmann et al 2010). As a result, it sits high on the list of targets for Western Palearctic listers visiting the country.

Though not truly migratory, it is a dispersive species outside the breeding season and thus prone to wandering. Western Palearctic records are sparse away from the Mauritanian coast, but also far from unknown. A total of three Moroccan records were listed by Thévenot et al (2003):

- 10 May 1947: offshore at Aguerguer

- 1 May 1968: Souss estuary

- 17 November 1988: adult near Agadir

There have since been a further six records involving seven individuals:

- 7 December 2003: first-winter at Dakhla

- 20 February 2004: adult at Massa

- 4 April 2005: Sidi Moussa-Oualidia

- 24 October 2006: first-winter at Massa

- 19 May 2009: two at Souss estuary

- 4 March 2010: immature at Pointe de la Sarga, Dakhla Bay

A quick glance at these nine records reveals something striking: only two stem from the vast expanse of Dakhla Bay, situated in southernmost Western Sahara, just 450 km to the north of Banc d'Arguin as the gull flies, seemingly a more likely location for the bulk of records of this species in the area. Instead, most records involve birds in 'true' Morocco, with five records (involving six birds) from the coastline south of Agadir (Souss-Massa National Park), some 950 km north-east of Dakhla Bay. Another record of an adult comes from the coast at Oualidia, a further 300 km to the north.

So, why the distinctly northward bias to occurrences in Morocco and Western Sahara, given this is the opposite of what we might expect? The obvious answer is observer coverage – it is no coincidence that the Souss-Massa National Park, boasting the majority of Grey-headed Gull records, is one of the most well-watched corners of the country, with excellent general birdwatching enlivened by the attraction of range-restricted species such as Black-crowned Tchagra and Brown-throated Sand Martin ensuring that the estuaries and surrounding areas are included on most birders' Moroccan itineraries. In stark comparison, Dakhla is a 1,000-km drive from Agadir and is only usually explored by more intrepid groups of birders. Though visited more regularly in the past few years, Dakhla Bay is an expansive and massively underwatched area which, in winter, boasts tens of thousands of birds. It seems likely that if coverage was as intense in this region as it has traditionally been at sites further north, there would be plenty more Grey-headed Gull records to show.

Importantly, however, the Moroccan records show that Grey-headed Gull evidently does disperse quite considerable distances from its known range: Agadir is 1,350 km from Banc d'Arguin as the crow flies, but considerably further if following the coast (and much further still if some of these birds originate from the far larger West African breeding population further south in Senegal). This notion of dispersal is further enhanced by a record from the Canary Islands and no fewer than three records from peninsula Spain, including two within the past year, as well as one from Gibraltar:

- 30 June-15 August 1971: Marismas de Hinojos, Huelva, Spain

- 17 Aug 1992: juvenile, Gibraltar

- 2 February 2005: first-winter at Las Palmas port, Gran Canaria (photo here)

- 11 June 2013: adult at L'Albufera de València, Spain (photo here)

- 23 March-4 April 2014: adult at Pinto dump, Madrid, Spain

The latest of these records, in central Spain, is the perhaps the most fascinating – at least in a northern European (British) context. Found at a landfill site south of the city in late March by members of the Madrid Gull Team, it lingered there until at least 4 April and was well photographed and videoed. The great significance is that the bird was found among large numbers of northbound Black-headed Gulls – a species that commonly winters along the West African coastline south to northern Mauritania (c1,000 around Nouadibhou; Olsen and Larsson 2003) and in small numbers south to Nigeria. With wintering grounds overlapping extensively with the West African range of the morphologically similar Grey-headed Gull, Black-headed Gull seems a perfect carrier species to 'bring' its counterpart northwards to Europe in spring. The Madrid bird would appear to be a vivid and contemporary illustration of this theory in action – the big question now is, if it leaves central Spain, how much further north will it travel?

Grey-headed Gull, Pinto dump, Madrid, Spain, 29 March 2014 (Delfin González).

Grey-headed Gull with Mediterranean and Black-headed Gulls, Pinto dump, Madrid, Spain, 29 March 2014 Delfin González).

Grey-headed Gull upperwing, Pinto dump, Madrid, Spain, 29March 2014 (Delfin González).

With this in mind, it is interesting to look again at the Moroccan records. While there is a spread right across the calendar including several winter records that may easily be explained by non-breeding dispersal, spring is the season when records are most concentrated – six of the nine records have come between late February and the second week of May, seemingly fitting well with the migration of Black-headed Gulls along the Moroccan coastline as they make their way back to Europe for the summer. Similarly, two further Spanish records (1971 and 2013) have come in June. Again, there is a case to be argued for these birds having migrated north with Black-headed Gulls in spring before going on to spend the summer in Europe.

Elsewhere, another recent record European record concerns a bird found in the harbour at Molfetta, to the north of Bari, Italy, in October 2012 and again present there sporadically between 4 June and late July 2013 – the first Italian record. Though not conforming to the apparent spring pattern observed in Moroccan and Spanish records, it nevertheless adds weight to the theory that Grey-headed Gull is periodically making it to Europe as a vagrant.

Second-summer Grey-headed Gull (left) with Black-headed Gull, Molfetta, Italy, 4 June 2013 (Cristiano Liuzzi).

Second-summer Grey-headed Gull, Molfetta, Italy, 4 June 2013 (Cristiano Liuzzi).

Second-summer Grey-headed Gull, Molfetta, Italy, 4 June 2013 (Cristiano Liuzzi).

Back on the North African side of the Mediterranean, Tunisian records involve one on 20 July 1988 and two on 28 July-3 August 1988, while in Algeria published records concern two adults and two immatures on 11 April 1981 and one adult and two immatures again on 15 April. Further east, Israel can lay claim to four records: three birds were seen in the Eilat area between March and September 1989, one of which also wandered into Jordan, and a fourth – a second-calendar-year bird – was reported migrating north with Slender-billed Gulls north of Eilat on 3 April 2013. In neighbouring Egypt, there is a single record concerning two adults at El Gouna golf course on 6 April 2002. Again, the pattern of these records is noticeable, with a clear bias to spring which only serves to reinforce the species' status as a regional vagrant at this season. Grey-headed Gull has also reached Arabia, with vagrants recorded in Saudi Arabia and Yemen presumably originating from East Africa.

Grey-headed Gull, Pinto dump, Madrid, Spain, 29 March 2014 (Delfin González).

Grey-headed Gull in Britain

Traditionally, occurrences in Britain have been dismissed as not involving genuine vagrants and, despite a few records, the species finds itself firmly embedded within Category E of the British Ornithologists' Union's British list as an escape. This is because Grey-headed Gull, alongside Silver Gull of Australia, is one of the commoner gull species known in collections, despite the fact that gulls generally are relatively rare in captivity. For example, in the early 1990s, Bourton-on-the-Water bird gardens (Wilts) kept around 20 Grey-headed Gulls and the Snowdon Aviary at London Zoo held a similar number of free-flying, unringed birds – which it still does today.

The first well-documented British record concerns an adult first found at Wilstone Reservoir, Herts, on 10 February 1991, and later seen in the roost at Brogborough Lake, Beds, on 17th, 19th and 20th, before last being noted flying off early morning on 21st. The record came during a particularly cold spell of weather, and the bird's propensity for roosting on ice made ascertaining a lack of rings straightforward. However, in light of the London Zoo birds being unringed, this does not necessarily prove a wild origin, and the time of year sits at odds with the spring and summer occurrences from elsewhere in Europe and North Africa. With that in mind, the record can only really be considered at best of unknown origin.

However, another adult, this time seen between March and August 1996, would appear to conform much more to the expected pattern of Western Palearctic occurrences. First seen at Ashleworth Ham, Glos, on 29 March, it relocated north to Bredon's Hardwick, Worcs, from 5-13 April. It was an adult in breeding plumage, again unringed and observed with arriving Black-headed Gulls – a record that, location aside, mirrors the 2014 Madrid individual very closely. This Midlands bird went on to spend the summer in the country, and was seen at Middleton Moor (Derbys) from 18 July through until its final appearance on 27 August.

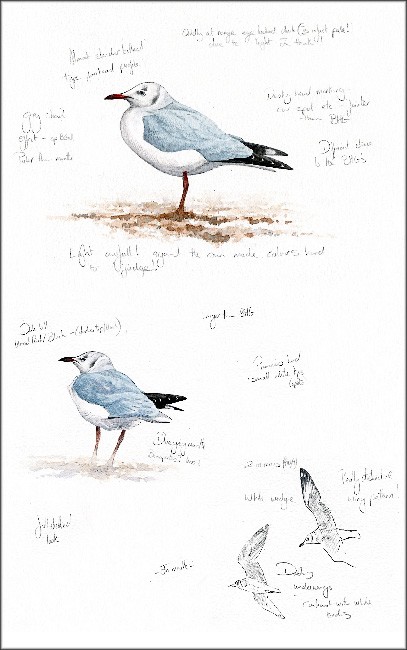

Grey-headed Gull studies, Middleton Moor, Derbys, summer 1996 (Artwork: Stephanie Hicking).

A third occurrence in London and the Home Counties during 2001-02 came at the time of a confusing series of records of birds resembling southern hemisphere 'hooded' (Grey-headed, Silver and/or Hartlaub's) gulls. The bird was first seen and photographed at Beddington Farmlands, London, in early March 2001. Though the rest of its plumage seemed within range of Grey-headed Gull, one notable discrepancy was the apparent weakness of the grey 'hood', though the dark tip to the bill colour may suggest that the bird was still acquiring breeding plumage at the time and the darkness of the hood itself is variable between individuals. This bird was latterly seen sporadically at Tyttenhanger Gravel Pits, Herts, from 27 May until mid-September, before reappearing there once on 11 November and then at nearby Hilfield Park Reservoir on 9 December. It then returned to Beddington, where it was seen regularly between 16 January and 17 May. There were also two reports of an adult from Wouldham, Kent, on 16th and 20 May 2002.

Putative Grey-headed Gull, Beddington Farmlands, London, March 2001 (Gary Messenbird).

Putative Grey-headed Gull, Beddington Farmlands, London, March 2001 (Peter Alfrey).

Evidently, a penchant for lingering in and around London for such an extended period of time is at odds with the apparent established pattern of vagrancy of Grey-headed Gull further south in Europe and, coupled with its arguably atypical plumage, the odds are that this individual was also a probable escape (and perhaps not even a pure cirrocephalus). This notion is arguably strengthened by the presence of at least one other confusing bird, of a similar ilk, present in Cambridgeshire in the early 2000s. An escaped Silver Gull was at Cow Lane Gravel Pits, Godmanchester, during 2000 and then, in 2002, a bizarre (and still not conclusively identified) bird – thought initially to be a Grey-headed Gull due to the very faint 'ghosting' of a hood – was seen over the Nene Washes on 9 April, relocating to a Black-headed Gull colony at nearby Prior's Fen in May. The bird appeared to show mixed features and, again, should be considered an escape with likely hybrid origin. What was presumably this bird then reappeared at Paxton Pits in June 2003.

Presumed Grey-headed Gull, Beddington Farmlands, London, March 2001 (Peter Alfrey).

Grey-headed Gull in North America

There are at least four records of Grey-headed Gull ('Gray-hooded Gull') in North America. The first relates to a well-documented adult in the harbour at Apalachicola, Florida (N29°43'51", W84°59'8.99"), on 26 December 1998. The bird was in full breeding plumage, corresponding to observations of breeding-plumaged birds along the Peruvian coast during that month. With Pacific coast populations the most likely source of a vagrant in Florida (the state has also hosted vagrant Belcher's Gull, from a similar range), there is no reason to believe the bird is anything other than wild in origin and it was accepted as the first for Florida and the USA.

There are also records from Barbados in May 2009 and at least one from Panama, but the most sensational record concerns an adult at Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, (N40°34'21", W73°58'56") from 24-29 July 2011, and is documented extensively in an excellent post by Amar Ayyash on his blog. Coney Island lies on a very similar latitude to Madrid and, before last year's Italian bird, represented the most northerly apparently wild Grey-headed Gull ever documented anywhere.

Adult Grey-headed Gull, Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, 31 July 2011 (Amar Ayyash).

Adult Grey-headed Gull, Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, 31 July 2011 (Amar Ayyash).

Though the source of this individual is almost certainly on the opposite side of the Atlantic to that of the series of Western Palearctic records, several interesting comparisons can be made. Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla), a common breeding species along the eastern seaboard of the USA north to Maine, routinely winters in numbers south to northern Brazil, where it may be found alongside Grey-headed Gulls which 'winter' north of their breeding range in numbers. A similar situation occurs in Ecuador, where Laughing Gull winters and Grey-headed Gull is a breeding resident. This overlap in range mirrors that between Black-headed and Grey-headed Gulls in West Africa, and similarly there is no reason why Laughing Gull should not act as a carrier species for Grey-headed Gull in the manner that Black-headed Gull appears to do in Europe. Indeed, the May record from Barbados would appear to strengthen the case for reverse-migrating Grey-headed Gull turning up as a spring (and summer) vagrant along the eastern fringe of North America.

Adult Grey-headed Gull (right) with Laughing Gull, Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, 31 July 2011 (Amar Ayyash).

Conclusion

Though Grey-headed Gull possesses a relatively small world population (c. 50,000 pairs) and is largely confined to the tropics and southern hemisphere, the presence of breeding in West Africa north to 20°N and an established pattern of Western Palearctic records – primarily in spring and summer – suggests that the species naturally occurs as a vagrant north to Europe on a rare but regular basis. Given the overlap in wintering range and the observation of the species together in Europe, it seems logical to assume that northbound Black-headed Gulls act as a natural carrier species of Grey-headed Gull to more northerly latitudes during the spring. The existence of summer records suggests that vagrant Grey-headed Gulls may go on to spend the summer in Europe after migrating northwards earlier in the year. A similar situation may well apply in the Americas, where Laughing Gull may replace Black-headed Gull as the likely carrier species, although the pool of records in North America is too small yet to draw any significant conclusions.

Given that Grey-headed Gull has reached as far as 40°N in both North America (New York) and Europe (Italy and Spain), it seems reasonable to assume that a vagrant – 'lost' far to the north of its natural range – could potentially penetrate to even higher latitudes, particularly given that Black-headed Gull breeds widely across central and northern Europe. Madrid, for example, lies 2,600 km in a NNE direction from the closest Grey-headed Gull colonies in northern Mauritania. It is 'only' a further 1,300 km to Britain on a similar trajectory. If a vagrant Gray-hooded Gull can travel the 5,000 km from Ecuador (at the northerly limit of its Pacific South American range) to New York, then the idea that a West African bird could travel 3,900 km to reach Britain seems entirely plausible.

In the past, British Grey-headed Gull records have been dismissed as escapes, and in some cases rightly so. However, the 1996 bird, found among migrant Black-headed Gulls in Gloucestershire in early spring and later going on via Worcestershire to spend the summer in Derbyshire, conforms much more to the established pattern exhibited by vagrants from southern Europe and North Africa, and as such must deserve greater recognition as a strong candidate for being a genuine vagrant. Future summers will no doubt produce further Grey-headed Gull sightings in Europe, and any future British record should be assessed with open-mindedness and consideration – particularly if falling within spring and/or summer.

Grey-headed Gull among Black-headed Gulls, Madrid, Spain, March 2014 – a sight to look forward to in Britain one day? (Delfin González).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Peter Alfrey, Richard Baatsen, Steve Blain, Rod Key, Gary Messenbird, Ken Smith, Steve Whitehouse and Barry Wright for photos and information on British occurrences, Amar Ayyash for his co-operation on the New York State record, and Delfín González and Ricard Gutiérrez for information on Spanish records and photographs of the 2014 bird respectively.

Resources

Isenmann, P, Benmergui, M, Browne, P, Ba, A D, Diagana, C H, Diawara, Y, and Sidaty, Z El A. 2010. Oiseaux de Mauritanie. Société d'Études Ornithologiques de France, Paris.Isenmann, P, Gaultier, T, El Hili, A, Azafzaf, H, Dlensi, H, and Smart, M. 2005. Oiseaux de Tunisie. Société d'Études Ornithologiques de France, Paris.

Isenmann, P, and Moali, A. 2000. Oiseaux d'Algérie. Société d'Études Ornithologiques de France, Paris.

McNair, D B. 1999. The Gray-hooded Gull in North America: first documented record. North American Birds 53: 337-339.

Mitchell, D, and Young, S. 1999. Photographic Handbook of the Rare Birds of Britain and Europe. Second edition. New Holland, London.

Olsen, K M, and Larsson, H. 2003. Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America. Christopher Helm, London.

Thévenot, M, Vernon, R, and Bergier, P. 2003. The Birds of Morocco: an Annotated Checklist. British Ornithologists' Union, Tring.