When an adult Kelp Gull was found among Yellow-legged Gulls at Paris Zoo in January 1995, the European birding scene was unanimously dumbfounded – how could it be that a potential first for the region had appeared so far north and at such an unexpected location? Unsurprisingly, the possibility of an escaped bird was mooted, but no evidence could be found to confirm that and, despite the seemingly impossible circumstances, it was accepted as a first for France and the Western Palearctic (WP).

Adult Kelp Gull, Paris Zoo, France, January 1995. The first European record of this species and clearly identifiable as ssp vetula ('Cape Gull') due to the dark eye (Frédéric Jiguet).

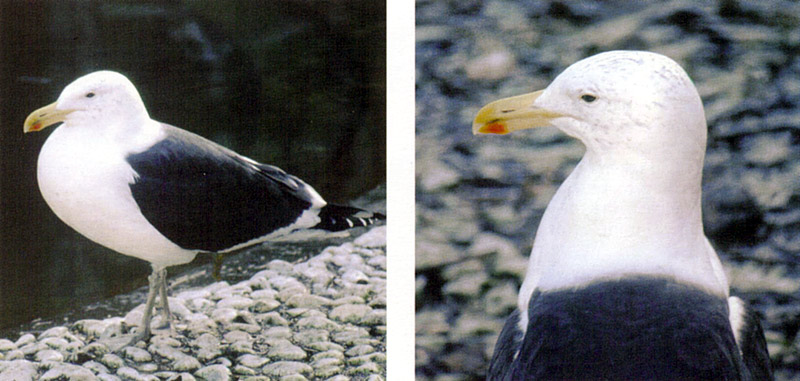

Kelp Gull Larus dominicanus is a familiar bird in maritime Southern Hemisphere, with five recognised subspecies. Nominate L d dominicanus is the most widespread, being found around the coasts of South America (including South Georgia and other subantarctic islands) and Australasia. Other subspecies include judithae of the subantarctic islands of the Indian Ocean, melisandae of Madagascar and austrinus of the Antarctic, but it is vetula of southern Africa which accounts for all accepted Kelp Gull records in the WP – and thus what this article focuses on. This taxon, commonly known as Cape Gull (and referred to as such hereafter for clarity), is often considered a candidate for full species status and adults are phenotypically distinct in that they have dark eyes, unlike the pale yellow-white of the other subspecies.

Since the turn of the century, the WP status of Cape Gull has changed rapidly. The species, which breeds commonly in coastal southern Africa, has been gradually spreading northwards along the coast of West Africa since the 1980s and, reflecting this, WP sightings began to take a significant upturn. Records include a long-staying adult at Banc d'Arguin National Park, Mauritania, from 1997-2007 and coastal Morocco in 2006 (one from Tenerife in 2001 has now been rejected). In 2008, four adults were seen at Khniffiss Lagoon, Morocco, which marked the beginning of a new chapter in the species' evolving status in the WP.

Pair of adult Cape Gulls on the beach at Akhfennir, near Khniffiss Lagoon, Morocco, 25 February 2017 (Bob Swann).

The Khniffiss situation initially proved confusing, with at least some of the birds seen in 2009 turning out to be Great Black-backed Gulls, seemingly breeding alongside (and sometimes in mixed pairs with) the local Yellow-legged Gulls. This in itself was an astonishing revelation, given Great Black-backed was previously only known to nest as far south as northern Spain, and represented a new breeding species for Africa. What's more, several hybrids (presumed to be Yellow-legged × Great Black-backed Gulls) were present around the colony, some of which looked strikingly similar to Cape Gull. However, despite these pitfalls, pure pairs of Cape Gull were also proven to breed in 2010 and subsequent years, confirming that the species was now reproducing in the WP.

Adult hybrid gull, either Yellow-legged × Great Black-backed Gull or Yellow-legged × Cape Gull, Khniffiss Lagoon, Morocco, 19 March 2011 (Vincent Legrand).

Adult Cape Gull, Khniffiss Lagoon, Morocco, 12 February 2014 (Mark Hows).

As a result of this, awareness of the species has increased exponentially and, with growing numbers of birders visiting southern Morocco and Western Sahara, Cape Gull records have become a regular feature from the coast as far north as Agadir in recent years. Generally associating with large, non-breeding flocks of Lesser Black-backed and Yellow-legged Gulls, most sightings involving adult or near-adult birds, although there a few documented occurrences of younger individuals.

Nonetheless, the rise in sightings is not simply due to greater awareness. Cape Gull certainly appears to be increasing in north-west Africa and is now breeding in small numbers at Banc d'Arguin, Mauritania – for example, six occupied nests with young were found on an offshore island in May 2019. What is particularly interesting is that this Southern Hemipshere gull has completely reversed its life cycle, breeding in the WP in the Northern Hemisphere spring.

Adult Cape Gull (centre) among Lesser Black-backed and Yellow-legged Gulls, Agadir, Morocco, January 2016 (Arie Ouwerkerk).

European expansion

Despite a significant upturn in north-west African records, the Paris Cape Gull of 1995 remained the only known European record until 2013. Then, that summer, Portuguese gull-watchers discovered three adults along the country's coastline, with birds at Peniche in May, Vila do Conde on 6 June and near Faro on 14 August. After a blank year for sightings in 2014, a fourth occurrence came from Costa da Caparica, just south of Lisbon, on 27 April 2015. A fifth was at Olhão, Algarve, in July-August 2016; in a curious twist, photos of an unknown gull taken at the same site back in 2009 came to light just after this and showed the same bird, making it a retrospective first for Portugal. This individual returned in 2017 and once more in August 2019; it is also thought to be responsible for the Faro record in 2013. A sixth – a near-adult – was at Espinho from 5-7 October 2018 and relocated to Matosinhos on 11th.

Adult Cape Gull, Costa da Caparica, Lisbon, 27 April 2015. Although the broad white trailing edge to the wing is extensively worn, the greenish legs, dark eye, bulbous-tipped bill and lack of extensive white in the primaries all readily identify this bird (Miguel Berkemeier).

Adult Cape Gull, Olhão, Algarve, July 2016. Note the remarkable bill structure, which suggests a male, as well as the greenish leg colour and restricted white mirror on p10 only. This returning bird was first photographed here in 2009 and was again present in August 2019 (Thijs Valkenburg).

Third-winter Cape Gull, Espinho, Portugal, 6 October 2019 (Samuel Patinha).

Spain, too, has started to produce Cape Gulls in recent years. The first – a near-adult – was on the beach at Ondarroa, in the Basque Country, on 21 April 2014. This site, on the northern Spanish coast, is just 40 km or so west of the French border. The second was found on 8 August 2017 close to the Portuguese border at Playa Punta del Caimán, Isla Cristina, Huelva, while the country's third – again on the north coast, and just 10 km west of Ondarroa – was photographed on 6 June 2019.

Between 2013 and 2018, all European records stemmed from coastal Iberia, where this predominately marine species was found among Lesser Black-backed or Yellow-legged Gulls between April and October. Given this, it seems likely that either of these species can act as a carrier for vagrant Cape Gulls in Europe, as Lesser Black-backed (migratory, wintering in West Africa and breeding in Western Europe north to Iceland) and Yellow-legged (dispersive outside the breeding season) are routinely seen alongside Kelp Gulls south to The Gambia and Senegal. Of course, Cape Gull, which continues to spread northwards along the north-west African coast, may also be dispersing northwards independently of its European counterparts.

Adult male Cape Gull, Isla Cristina, Huelva, Spain, 8 August 2017. This particularly large bird, with its spectacular bill, is considered probably the same individual as seen intermittently at Olhão, Algarve, Portugal, since 2009. Note the considerably larger size than the surrounding Lesser Black-backed Gulls (Jeffrey Huisenga).

A curveball then came on 21 February 2018, when a near-adult Cape Gull was found well inland in northern France at Bouqueval landfill site, on the northern outskirts of Paris, and was still there a month later (more on that bird here). While avian vagrancy tends to produce perverse coincidences from time to time, this must be one of the most bizarre. Extraordinarily, it favoured a site just 25 km from Paris Zoo, where the famous 1995 bird was recorded, and at a similar time of year – both occurring well outside the established pattern of records that has emerged from Iberia in recent years.

Third-winter Cape Gull, Bouqueval landfill site, Val-d'Oise, France, 22 February 2018 (Thibaut Chansac).

Prior to this, British and Irish birders would have considered checking arriving flocks of migrant Lesser Black-backed Gulls in spring – as well as northward-dispersing Yellow-legged Gulls in mid-summer – the best chances of bringing a vagrant Cape Gull to either country. However, the discovery of a second French bird in the winter months seemed to highlight that just about any time of year might produce.

It would be churlish not to mention that there is already a claim of Kelp Gull from Britain – a sub-adult seen at Dungeness, Kent, on 16 July 2001. Photos of this bird can be found here – the strikingly pale eye rules out this bird being a Cape Gull, particularly given that the bird is not an adult. It was deemed not sufficient to be accepted as a first for Britain and thus Kelp Gull remains as a candidate for future addition to the national list.

Kelp Gull in North America

Kelp Gull remains a major rarity in North America. Canada and the lower 48 states currently share around 15 records, all of which have concerned adults or adult-types, with a third-year bird seen in Indiana the only younger individual (no first- or second-years have ever been recorded). There are single reports from as far north as Nova Scotia and even Newfoundland.

Significant records include a returning bird in Maryland and Delaware for several years, which was well known for frequenting a seafood restaurant where it gladly accepted scraps. There are recent inland sightings from Pennsylvania and Ohio, both of which were seen on landfill sites.

All North American records appear to relate to the nominate dominicanus subspecies of Kelp Gull. This one was photographed as Ushuaia, Argentina (Richard Collier).

The exception to the rule is Louisiana. An intermittent hybrid phenomenon occurs on the Chandeleur Islands, where Kelp Gull hybridises with American Herring Gull. The colony totalled around 50 pairs in the early 2000s, but as of last summer only about 12 pairs were observed. They were completely absent after Hurricane Katrina submerged their breeding islands for a few years from 2005.

The Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico also has a steady number of records, and the species seems to be gradually increasing there in tandem with Lesser Black-backed Gull.

Identification

When seen well, adult Cape Gull is a distinctive bird, but it could quite easily be overlooked among both Lesser and Great Black-backed Gulls if viewing conditions are less then ideal. Size and structure is somewhat intermediate between those two species, with larger males appearing bulkier, shorter winged and almost Great Black-backed in size, while females can be considerably smaller and more elegant looking. The bill is heavy and exhibits a bulbous tip, sometimes spectacularly so in males. It is consistently long legged which, when combined with overall structure, gives a distinct impression of both bulk and ranginess.

Adult Cape Gull, Tanji, Gambia, February 2012. A classic bird, with dark eye, bulbous-tipped bill, blackish upperparts, broad white trailing edge to the wing and greenish-yellow legs (Paul Cools).

In terms of plumage, the extremely broad white trailing edge to the wing should be obvious both at rest and in flight. The upperparts are very black, even darker than Great Black-backed, while the legs vary between grey-green to yellow-green and the bill is more of a paler yellow than the often orangey-yellow of Lesser Black-backed. The eye is dark, with this particularly obvious on closer views. In flight, the lack of white in the outer primary tips is both consistent and distinct – adults only ever show a small mirror on p10, compared to a large white tip to p10 and mirror on p9 in adult Great Black-backed.

Third-years, such as that in Paris in 2018, can also be identified by a combination of the structural and plumage features described above, but with a variable extent of immaturity. Younger birds are arguably less distinctive, but are nonetheless readily identifiable with decent views. Chris Gibbins's exhaustive photo-essay on the identification of first-year is unmissable and can be read online here.

Immature Cape Gull, Walvis Bay, Namibia, December 2016. Plumage is swarthy and bill structure is also very distinctive so, with good views, a bird like this would stand out among its European counterparts (Martyn Sidwell).

Conclusion

Given the northward expansion of its range and resultant increase in occurrence in north-west Africa and south-west Europe, the likelihood of a Cape Gull making it to British or Irish shores seems to have increased greatly over the past decade, to the point at which it could be considered almost expected to put in an appearance at some point in the near future.

Cape Gull appears to be a predominately coastal species – all Moroccan and most Iberian records have been on or close to beaches – but the 2018 French sighting illustrates that it may well be an inland landfill site that produces the first British or Irish record. Reports of Kelp Gulls on rubbish dumps in the US reinforce this. Given that adults or near-adults have dominated European sightings so far, it is likely that an older bird will be most likely to turn up, but this may be due to a lack of familiarity with younger plumages, and this possibility should not be ignored.

While spring and summer perhaps remain the optimal time to be searching for this species, the French birds demonstrate that it could appear at any time of year and, as with all other rare gulls, careful and persistent scrutiny of concentrations of gulls would give any prospective finder the greatest chance of a once-in-a-lifetime discovery.

Acknowledgements

The MaghrebOrnitho website is a very useful source of up-to-date Cape Gull sightings in Morocco and Western Sahara. Thanks to Pedro Nicolau for providing details on all accepted Portuguese records of Cape Gull, and to José Luis Copete for his summary of Spanish occurrences. Many thanks also to Amar Ayyash for sharing his expert knowledge on the status of Kelp Gull across North America.

References

Bergier, P, Zadane, Y, amd Qninba, A. 2009. Cape Gull: a new breeding species in the Western Palearctic. Birding World 22: 253-256.

Chansac, T, and Wroza, S. 2018. Rarity finders: Kelp Gull in northern France. BirdGuides.com. Available online: www.birdguides.com/articles/rare-birds/rarity-finders-kelp-gull-in-northern-france

Jiguet, F, Jaramillo, A, and Sinclair, I. 2001. Identification of Kelp Gull. Birding World 14(3): 112-125.

Jiguet, F, and du Rau, P D. 2004. A Cape Gull in Paris – a new European bird. Birding World 17(2): 62-70.

Jönsson, O. 2011. Great Black-backed Gulls breeding at Khniffis Lagoon, Morocco and the status of Cape Gull in the Western Palearctic. Birding World 24: 68-76.