Ptarmigan is always high on the wish lists of birders and photographers visiting the Scottish Highlands in winter. Finding Ptarmigan is one thing, but knowing where to photograph them is another challenge. It took me five climbs to see my first one and that was when the love affair started. I make no bones about it — Ptarmigan are my favourite bird.

This article represents the culmination of over 200 days spent in the mountains over the last five years watching, photographing and above all enjoying Ptarmigan. I have guided more than 300 people (mainly photographers) up into the hills and have failed to see the species on fewer than 10 occasions. In this article I aim to provide information to get you the best possible photographic encounter with Ptarmigan while staying safe enough to come back and do it all again another day.

Ptarmigan, undisclosed site, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Preparing and staying safe

The Cairngorms and Highlands are a fabulous place but they are not without perils. In all months of the year, experienced walkers and climbers are injured or worse; in winter 2013/14 alone, 12 people died in the mountains of the Scottish Highlands. If necessary, have the confidence to turn back and try another day. The majority of those that died between 1950 and 1990 did so because they carried on when the weather set in. Snow can, and often does, fall in any month of the year. The following is a checklist of what to consider before heading out.

Weather

In many ways the weather required to see/photograph Ptarmigan corresponds with when it is safe to do so. Fortunately there are very detailed and up-to-date forecasts released by the Mountain Weather Information Service (MWIS). It is far more accurate than any other service and tells you the key information that you need to know. Weather can and does change quickly and you should always prepare for the worst case scenario.

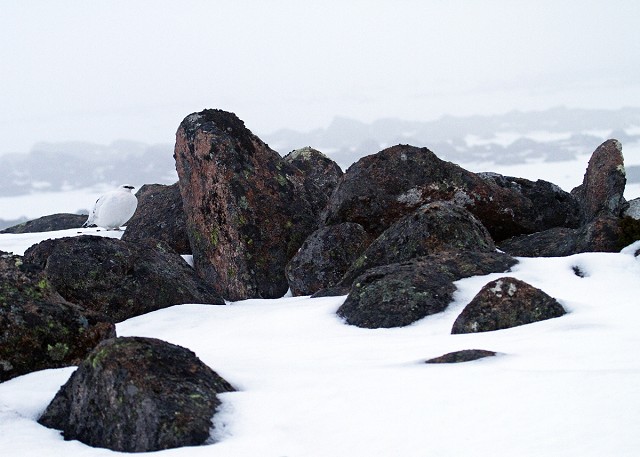

Ptarmigan, undisclosed site, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

- Wind: I would not head up if anything over 50mph was in the forecast. You need to consider the wind strength, gust strength, direction and wind chill. On winter days things can seem very calm even at mid altitudes, yet the wind is likely to be over 70 mph on the higher hills in anything but high pressure. I have found that in winds over 50 mph walking becomes difficult, finding Ptarmigan becomes very difficult, and holding a camera or binoculars steady is impossible! Walking along an exposed ridge is incredibly dangerous in any wind. Wind from the north is generally colder and can add a wind chill factor of a further –10°C, though often more.

- Precipitation: I would not head up if anything more than light precipitation is forecast. Some of the most frightening experiences I have encountered are during 'white outs' when it can become impossible to see more than a few feet in front of your boots. This would be particularly dangerous if you do not know the mountain well as in all likelihood the path (if you were following one) would have disappeared. A surprising number of fatalities occur very close to car parks as walkers become disorientated and cannot find shelter in time. Of course, trying to find Ptarmigan in such conditions is pretty miserable too!

- Cloud: I would not head up if the chance of cloud-free Munros was lower than 50%; this is an important factor, and often overlooked. Being in the cloud base is essentially like standing in fog: visibility is very low and finding and photographing Ptarmigan is again very troublesome. Obviously there are also dangers if you can no longer see ahead of you.

Ptarmigan, undisclosed site, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

- Sunshine: Handily the MWIS gives you an idea of the air clarity for the mountains. This is great for photographers, especially in the longer days of spring and summer. If air clarity is high then you want to endeavour to be on the hill at dawn and dusk for the golden light. Shooting more than an hour or two after sunrise is likely to give terrible shadows and "crunchy" feather details.

- Temperature: If other conditions are favourable, I generally won't be put off by any temperature; I just make sure I prepare effectively (see gear below). Bear in mind that liquids can freeze quite quickly in temperatures of –10°C or colder. It is also very important to control sweating as any moisture next to the skin can cause problems leading to hypothermia. This is especially relevant for photographers who may climb rapidly and then often wait long periods on the snow or cold boulders.

- Freezing level: This is particularly in regard to avalanches (see the Sport Scotland Avalanche Information Service, SAIS). The best advice is to read the forecast and steer clear of cornices and slopes between 25 and 45 degrees, especially during 'freeze-thaw' cycles.

Gear and other things to consider

- Footwear: Firstly, a waterproof boot with good ankle support is a must. I am often asked about snow shoes, crampons and ice spikes; in general most of the people I have guided have managed without these. However, if you notice that the terrain is icy, do not continue unless you have the correct equipment. I once slipped in an 'ice field' and 30 metres later my slide was brought to an abrupt halt by a large boulder — not pleasant! Areas where snow is compacted are often also very treacherous. Frustratingly the most likely place for this to happen is on the path itself, so take care at all times. An ice axe can help but only if you know how to use it.

- Clothing: A wickable base layer is very important for removing moisture from the skin during winter. Most other clothing is obvious: fleeces, waterproof coat and trousers, and so on. In general, it is best to layer up in all seasons so you can add or remove clothing as conditions change. If you want more advice or guidance on recommended brands then get in touch. Sunglasses can be handy especially for searching the snow.

- Tripod: I generally travel without a tripod as I like to shoot low. Instead, I normally find suitable support from a boulder or by lying in the snow. I know that won't be to everyone's taste, but that's my preference when taking photos.

- Sustenance: Though liquids are heavy to carry, always take plenty of water plus chocolate or sweets just in case you get stuck.

- Other items: A map and compass (and knowledge of how to use them!) are very handy. I also have an emergency whistle on my key ring and let others know where I am going and when I intend to return. With a group I sometimes carry a rope and always have a fully charged mobile phone (reception on Vodafone is fairly reasonable in most parts of the Cairngorms at higher altitudes)

- General health: The normal distance covered in a day's shooting is between three and six miles. In summer a fit and healthy photographer could easily cover 25 miles if they wanted to. The terrain can be steep. Think carefully about whether you can make it and most of all if you will still enjoy it when you do. I have guided several people in their 80s, heavy smokers and some with various replacement body parts so it is possible! Don't be put off, but do be sensible and honest with yourself. This is not a race — it is normally possible to get to Ptarmigan within 90 minutes in deep snow even with a slow pace and regular stops.

OK — so now you're ready, where are the best places to go looking for Ptarmigan?

Finding and photographing Ptarmigan in winter

Wherever you may live and whatever you do in life you, will invariably have to go out of your way to see a Ptarmigan in Britain — they rarely venture down from the highest mountains, don't come to feeding stations and there are no comfortable hides with flushing toilets to sit in and wait. You nearly always have to go and experience their habitat and their conditions in order to spend time with these fabulous birds. You must enter their domain. What is striking is how uncomfortable this can still be even on the best days in some winters.

Ptarmigan, Cairn Gorm, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Here I provide a series of the best places to find Ptarmigan in Scotland.

Cairngorm Ski Car Park: After high winds and heavy snow in winter, Ptarmigan can be seen from the car park. They are very much hit and miss, however, and a good scope is normally required. The most reliable area to scan is the ridge to the right of the ski area, south-east of the car park. This is called 'Windy Ridge'. In winter there are normally some Snow Buntings hanging around the car park too, so keep your eyes peeled.

Snow Bunting, undisclosed site, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Cairngorm 'Ptarmigan' Restaurant: If you take the funicular up the hill this is one place you can get surprisingly lucky as Ptarmigan stroll by as you enjoy a hot chocolate. Scanning in all directions from the viewing area can produce results. Again, luck is required and as leaving the restaurant is restricted it can be a frustrating experience. The viewing platform is also good for Ring Ouzel and the occasional Dotterel at the right time of year.

Carn Ban Mor: Although more walking is involved (a round trip of about four hours), Carn Ban Mor represents a great place for a walk into Ptarmigan country with the added bonus of being a regular stop-off point for Dotterel in spring and summer. Another of the main advantages to Carn Ban Mor is that this is an individual peak, so you know Ptarmigan are there: it's just a case of finding them. Keep looking and eventually you will stumble across them — I have always found a minimum of 10 or so birds on the highest point.

Glenshee: If you manage to reach Glenshee (the road is notorious for winter closures), then scoping towards the Cairnwell offers the best chance of seeing Ptarmigan with minimal effort in the whole Cairngorms. This is also one of the best places in winter for Mountain Hare and Snow Bunting, as well as the more common Red Grouse.

Applecross: The legendary 'Pass of the Cattle' remains the only place where Ptarmigan can be potentially seen from the car in Britain. It is far from guaranteed but if climbing mountains is just not your thing, then this location is probably your best shot. The area is great for raptors including Peregrine and Golden Eagle. Make sure you visit on a clear day.

The best way to get close to Scottish Ptarmigan

Even though I am up in the hills two to three times a week, Ptarmigan can be frustratingly hard to find and approach — this is especially the case when snow is deep or there are periods of high wind. In the wet and windy winter of 2013/14 where birds formed 'mega-flocks' of 50 or more birds for much of the winter season, they were very flighty. Once in these flocks the chances of failure are much higher because the birds can be concentrated in a small and sometimes inaccessible area.

Ptarmigan, Cairn Gorm, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Once you have found Ptarmigan you need to approach them carefully but 'deliberately', in much the same way one might approach Sanderling feeding on a shoreline. The most important thing in the approach is to stay below the subject. If you try and come from a higher slope or descend over a boulder, you will almost certainly flush the bird(s). If you find a Ptarmigan below your position it is best to walk to a contour lower than the target and then re-engage in pursuit once you are beneath the bird. I would not recommend crawling as this seems to agitate the Ptarmigan. However, lying down within range is fine.

Ptarmigan, undisclosed site, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Once within range I would generally take up a position and wait for something to happen. Ptarmigan can be docile and with a careful approach it can be possible to get very close. Indeed I have often got groups of three or four within an ideal range only for the Ptarmigan to move too close to focus! Once a Ptarmigan is on the move it is important to move quickly with them and try and get ahead of them. In winter they rarely take flight but prefer to walk or run. Trying to work out which way they are heading gives the best opportunity to capture images on snow fields or other desirable habitat.

Photographing Ptarmigan in winter (October to April)

Many mountainous areas hold good numbers of Ptarmigan and getting to know a new area is a great experience. For example, Ben Wyvis is one such area where there are many good areas for Ptarmigan, and you have the added bonus of being fairly certain you won't see another soul. However, for the practical reason of a reduced climb, the Cairngorms offer the photographer the best chance for the least effort. I'll focus on the Northern Corries but much of the information is transferable to other places.

The highlight of the Ptarmigan year, for me at least, comes in winter when they turn pure white. Ptarmigan plumage is closely related to changing day length so they will be white even in years with little or no snow. In winter I would stick to the Northern Corries in the Cairngorms; the three large 'craters' that spread south-west from Cairn Gorm itself — Coire Cas, Coire ant Sneachda and Coire an Lochan. These are generally well-travelled routes by ice climbers looking for excitement on the steep walls up ahead, so there should be some sort of path or more obvious route up to the key areas. Aim for the the boulder fields that can be found as you approach the back wall of each corrie. Be aware that with snow on the ground, there are several frozen burns that are concealed. Do not leave the path, and even then you need to keep your wits about you — falling into one would have severe consequences. A guide who knows the area can be invaluable. The walk into the boulder fields takes between 60 and 90 minutes depending on a range of factors; snow cover, snow depth, ice, wind, walking pace and so on.

Now you're in the right area, but where are those Ptarmigan? It's worth nothing that the species is very well camouflaged at all times of year and birds are often bold enough to let you walk within a few feet without moving — so be patient.

Ptarmigan, Cairn Gorm, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Despite the Latin name (Lagopus muta), Ptarmigan are far from silent and on calmer days this is the first sign you are in the right area. Male Ptarmigan call frequently, their retching call reverberating around the boulders and carrying for hundreds of metres on a still day. While calling, males sit proudly on boulders, proclaiming their presence to nearby birds. Often, shortly after calling the male flies up and reveals his whereabouts, which can be very helpful. The females call too but it is much less frequent and less helpful in finding birds.

Ptarmigan, Cairn Gorm, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

On days after heavy snowfall or strong winds, finding Ptarmigan can be extremely difficult. As mentioned previously, the birds form concentrated flocks and these can be impossible to locate over such a vast area. The best places to look are wind-blown slopes such as 'Windy Ridge' or onto the wide ridge of Miadan Creag an Leth-choin (only recommended for the experienced). As with all flocking birds, it only takes one 'twitchy' individual to spook them all. Not only does this lead to disturbance, which is to be avoided, but it means getting near them again would be a wasted journey. Generally, once flushed the Ptarmigan are alert (the camouflage is blown?) and it is best to find another subject. If you do manage to find a flock of 20 or more birds and they 'accept' you, it will almost certainly become a lifelong memory as you watch them eat, sleep and just survive in this most harsh of environments.

Ptarmigan, Cairn Gorm, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Still days in late February are the best for interaction between males. This is also a great time for photography as there is lots of activity, should be plenty of snow and the males are generally too preoccupied by squabbling to care about people. By March the birds are into their spring moult.

In typical years, March and April are probably the two best months for guaranteed photo opportunities if you know where to look. The birds look great as they are in various stages of moult. They are scratching around (moulting looks somewhat irritating!) and the males are still very active. The key to success at this time of year is to find an unattached male or to find a female. With nothing to protect, unattached males are often much bolder and are also continually on the lookout for other pairs — this can be great for action.

Ptarmigan, Cairn Gorm, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

You can be almost certain that if you can find a female she will tend to sit and allow an extremely close approach and then start to attract males over. Even if the male flies off (please try to avoid disturbing them) he will return typically within five minutes. With lots of interaction between pairs this is also the best time of year to try and get flight shots.

Ptarmigan, undisclosed site, Highland (Photo: Marcus Conway — ebirder)

Self-guiding for Ptarmigan is certainly possible in the Scottish Highlands as long as the right precautions are taken. However, if you would prefer a guided experience with the latest information on activity and locations please feel free to contact us via the ebirder website. We can't guarantee success, but if we do dip out we will happily take you up there again for free — if you can face doing it all again, of course!

ebirder

ebirder offer a range of nature and bird photography holidays and tours across Scotland including the Cairngorms, Mull, Islay, the Outer Hebrides and Speyside. In addition a photography day guiding service covers species such as Crested Tit, Ptarmigan, Otter, Mountain Hare, Dotterel and other Scottish specialities. Check out the website at ebirder.net.

Further reading

If you only get one book then I highly recommend Best Birdwatching Sites: Scottish Highlands by Gordon Hamlett. Even though I am now living in the Highlands, I know I can still turn to this excellent guide to discover something new. An absolute must for all birders and photographers.

Watson, A. 1992. The Cairngorms: Scottish Mountaineering Club District Guidebook, 6th edition.

Forrester, R., & Andrews, I. et al. 2007. The Birds of Scotland. Scottish Ornithologists Club

Madders, M. 2002. Where to Watch Birds in Scotland. Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd

Thom, V. M. 1990. Birds in Scotland. T & AD Poyser