We are now at the end of the winter and already the first spring moths have been recorded across the country. For those new to mothing, or hoping to see and learn more in the coming year, described below are a variety of moth traps that can be used in your garden or perhaps in a nearby wood. Later, in Part II, will be some ideas and hints on how best to deploy them in order to attract the widest variety of species. As well as light trapping for moths, there are other simple field techniques that can be used and which can be better for attracting certain species.

Most moth traps use an electrical source to power lamps of various designs and technical specifications. Unlike domestic household bulbs, which give off tungsten light highly visible to the human eye, moth trap lamps emit a much wider range of light frequencies including those below the blue end of the spectrum in the ultraviolet (UV) range. It is the ultraviolet and lower frequencies of the white light band, which are most attractive to moths. There have been several hypotheses as to why light attracts moths in the first place, but none is entirely satisfactory. Different species react in different ways, depending on the brightness of the light, and it could be a long time yet before the real process is fully understood.

So moths come to light, but which light? The ultraviolet band is produced by mercury vapour discharge, and two types of lamp which do this are the MV lamp and the low-pressure fluorescent tube (Actinic), both of which are readily available. The lamps used most frequently by lepidopterists are the 80-watt and 125-watt MV bulbs. Following just behind in popularity are the Actinic strip tubes that range from 6 watt, through 15 watt to 40 watt. Choosing whether to use 80-watt or 125-watt MV could depend on how large your constant effort site is. If it is your garden, you may need to consider the position and proximity of your neighbours' houses. In a suburban setting the illumination effect of a 125-watt MV is slightly more than an 80-watt. Large pieces of hardboard, painted white, can be used to screen the lamp from any direction and at the same time can also be used as windshields. The much duller 'medium-blue effect' of an Actinic may be preferable if you want your nocturnal activities to remain low-key, and Actinic lights do not require rain guards, as they run cool. If you are lucky enough to have a larger garden with lots of shrubs and trees, a 125-watt MV will produce more moths. You may also need to think about electricity consumption if you plan to run the trap frequently. Both MV lamps and Actinic fluorescent tube set-ups require electrical chokes to regulate the current from the mains or a generator. The construction and connection of these units needs to be done by a recognised dealer or qualified electrician.

There are now a wide range of moth traps available either commercially or, if you are half-decent at craft or woodwork, you can make one yourself. Perhaps the most popular and successful trap for the garden, due to its weather resistant construction and proven physical retention of the overnight catch, is the Robinson Trap. Constructed from plastic, it is fairly lightweight, with a strong circular collecting base, transparent collar and a circular baffled entrance cone which houses the upward-pointing MV bulb. Above the bulb, a suspended transparent circular rain guard will stop all rain from damaging the hot bulb and entering the trap. The only disadvantage of this trap is the slightly bulky nature. It is also more difficult to inspect the trap during the course of the night, as you have to reach further in to examine the egg boxes.

An assembled Robinson Trap with MV bulb

(photo: Tim Barker).

The most cost-effective all-round trap is the Skinner Trap. Flat-pack wooden versions are available from several commercial outlets and several can be fitted into a car when travelling long distances to carry out multi-trap field surveys. Skinner kits tend to retail at about half the price of a Robinson. The central wooden crossbar houses the bulb holder and rain guard. Two large, angled pieces of clear Perspex have dual purposes, in both deflecting moths downwards into the holding part of the box and allowing easy visual inspection and hands-free access to egg boxes, especially useful when going through the night trap rounds or for social or public demonstrations.

An assembled Skinner Trap with MV bulb (photo: Steve Whitehouse).

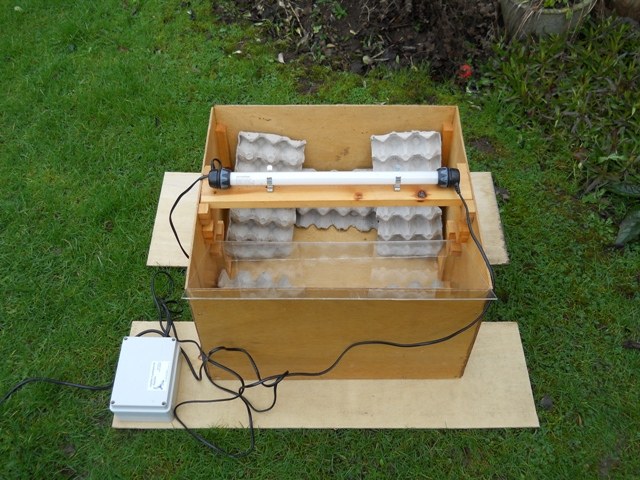

Skinner Trap boxes can be made in the home workshop and can be easily modified so that the central crossbar carries either a single 15-watt or a double 30-watt Actinic tube set up.

An assembled Skinner Trap with 15-watt Actinic Tube (photo: Steve Whitehouse).

An assembled Heath Trap

(photo: Jon Clifton).

Scientific comparisons have been made in the performance of the above three traps. It has been found that, in similar circumstances, species numbers in overnight catches are similar between Robinson and Skinner Traps, whereas those for modern Heath Trap set-ups are about 25–45%. However, Skinner Traps must be fully processed before dawn, as moths find this trap design quite easy to escape from after daybreak.

Another less complicated source of light for a trap is the 160-watt 'blended' MBTF lamp, which requires no choke and can be plugged directly into the mains or generated power supply. The disadvantage with this type of bulb is that they run much hotter than the 80/125-watt MV bulbs and only a small amount of rain will cause them to explode, so they should always be used with rain guards. As with all things electric, follow the manufacturer's recommendations and make sure that all plug-ins, cables, connections and junctions are protected from rain and dampness, even if this means resorting to plastic bag covers for the overnight period. Specially designed plastic junction covers can be obtained from commercial suppliers.

For serious field or excursion moth-trapping, one needs to invest in a quality portable generator that is both lightweight and quiet. Cheap alternatives are available, but these are often temperamental to start, heavy and noisy, and if used frequently will need servicing quite regularly, which can end up being a false economy. The three proven lightweight models to consider are the Honda Eu10I, the SDMO Booster 1000 and the Stephill SHx1000. If the optimum oil level is maintained and the units are stored in dry conditions, they can run for three to four years between full services, depending on use. A strong stainless steel chain with heavy duty padlock or similar type of bicycle lock is needed to secure generators to trees or man-made structures when operating in the field.

SDMO Booster 1000 generator (photo: Steve Whitehouse).

Other essential items of equipment that are a little easier on the pocket are a range of glass tubes and plastic pots for securing and temporary housing of individual moths. These need to be of a fair range of sizes and shapes, considering you may be interested in micros as small as 3mm or large macros with wingspans of 2–3 inches. Larger jars or used plastic ice-cream tubs are better for hawkmoths. Old, white sheets are best spread flat underneath your trap so that the many dull-coloured moths that have recently arrived show up well and can either be potted or transferred into your trap box. Larger, square-type commercial egg boxes are best for use inside both Skinners and Robinsons. These can normally be obtained by asking Chinese restaurant owners if they have any used ones they don't need — normally successful if you've just bought a take-away meal! Most moth-ers cut these in half for easier placement. Depending on how many traps you take into the field, a minimum of one 50-metre cable reel per trap is needed so that traps can be far enough apart to catch different moths. A strong, robust torch with a powerful beam is needed and the Maglite range is suitable for most purposes. Smaller 'head torches' are useful, as they leave your hands free, and have recently been on sale at very reasonable prices at Homebase. Finally a small quality hand lens or magnifying device will be needed to identify many of the smaller moths, especially the micros.

Twelve types of glass tube and plastic pots (photo: Steve Whitehouse).

Nearly all the above equipment can be purchased from the specialist online Anglian Lepidopterist Supplies. This organisation sponsors many insect conservation projects and most equipment comes with detailed instructions on use.

A short film demonstrating some mothing techniques

Reference

Fry, R. & Waring, P. A Guide to Moth Traps and Their Use. The Amateur Entomologist. Volume 24