In a rapidly changing world, headlines about the many insect species losing as a result of human activity are depressingly commonplace these days. For all the losers though, the Anthropocene has some remarkable winners – and among European butterflies, few can be more impressive than Southern Small White.

Female Southern Small White near Maastricht, Limburg, on 27 September 2015 – at the time, the first specimen for the Netherlands (Pieter Vantieghem).

Historic status

Historically, this was essentially a Mediterranean species, enjoying a relatively broad distribution across the warmer parts of southern Europe. In the west, it is local on the Iberian Peninsula, spreading east into the Pyrenees, over south-east France and the southern edge of the Alps, down the Italian peninsula, into the Balkans, and as far as eastern Turkey. Outposts in Morocco and on the Slovakian-Hungarian border are probably now extinct. Despite its broad range though, this species is often overlooked, thanks to its similarity to other species of Pierid, such our own native Small White, and its quite localised distribution in some areas, where it forms small colonies around its foodplants – a number of crucifers of warm, rocky places, particularly Candytuft (Iberis) species.

Indeed, relict colonies of the subspecies andegava were only discovered in the Meuse Valley in north-east France and Luxembourg in the 1970s, where it was largely overlooked by local lepidopterists until further searches in 2012 revealed it breeding at a number of old quarry sites in the region. Similarly, in Switzerland in the 1980s, the subspecies alpigena was largely limited to rocky south-facing slopes in the Rhone Valley, where it was thought to be acutely threatened by construction activity and the expansion of vineyards into its habitat.

All of this makes the rapid expansion of alpigena in the last decade an even more remarkable story, both of a butterfly totally confounding expectations about its ecology and dispersal, and an impressive recording effort that has charted its rise.

Expansion

Around the turn of the millennium, alpigena began to expand its range out of southern France, appearing in the Rhone-Alps in 2001 before spreading up the Rhone Valley and arriving in south-west Switzerland in 2005 (some distance from its known haunts in the west of the country), with the first record for the Geneva area since 1918. From there, it continued north-eastwards and reached the northern edge of the country in 2008, arriving in Germany in the same year when a female was found in the municipality of Grenzach-Wyhlen in the far south-west of the country. After this, its expansion continued apace, and by 2013 it had been recorded across most of the southern German provinces, continuing north and west into The Netherlands, where it was first found at Limburg in September 2015. It was then found just over the border from there in Belgium in 2016 and has since spread right through both countries to the North Sea coast.

The remarkable expansion of the Southern Small White in central Europe. Data is from GBIF and although it represents a fairly complete picture for the Low Countries, records are a bit more patchy for Germany and France where the butterfly is more widespread than this figure suggests.

While moving northwards, Southern Small White seems to have mostly followed the lower valleys, such as the Rhone into Switzerland and then the Rhine north from there. These presumably provide warmer, more favourable habitat that promotes expansion of this warmth-loving species, in contrast to cooler upland areas, like the Vosges, which slowed movement into northern France, as well as heavily agricultural and forested regions like the Ardenne that have reduced movement west from the Low Countries.

Still, this takes nothing away from the species' remarkable rise, covering the distance from the Swiss Alps to the North Sea coast in around 10 years – about 80-100 km per year. Although its expansion through The Netherlands and Belgium has been well-charted, thanks in part to the large community of recorders and verifiers using each country's Waarneming platform, quite how much of northern France and to a lesser extent Germany has been colonised as the butterfly spreads east and west from the Rhine Valley is less clear. It has however been recorded on the northern coasts of all of these countries now, with records just a stone's throw away across the channel at Calais (in 2019) and Dunkirk (in 2020), while the most northerly record so far was also last year, at Kiel (roughly the same latitude as Scarborough, North Yorkshire).

Male Southern Small White, Teuven, East Flanders (Pieter Vantieghem).

Quite what has driven this remarkable expansion remains unclear. Although most authors agree a rapidly warming climate must play a role, this is not a species slowly tracking suitable conditions northwards. Modelling in the Climatic Risk Atlas of European Butterflies (admittedly at a very coarse scale) suggests that even under the most extreme climatic scenarios, the Low Countries will not be suitable for Southern Small White until well after 2050. While its Candytuft foodplants are widely cultivated in gardens, transportation of eggs and larvae is not thought to have been important. It certainly seems true that the butterfly is benefiting from the new habitat provided by these garden plants, which are grown in abundance in the Low Countries, and perhaps the favourable microclimate of their warm urban environment, but neither of these seem sufficient to explain the suddenness of the species' rise. Southern Small White has transformed from being a largely sedentary Mediterranean butterfly of small, dense colonies to a swashbuckling globetrotter, advancing northwards at a speed matched by no other European butterfly.

Consolidation and further expansion

Although now recorded across the Low Countries, Southern Small White is still not especially numerous there, and is still relatively scarce in the north and west of The Netherlands and western Belgium, where it has arrived more recently. In fact, on transects, the commoner Green-veined and Small Whites are several orders of magnitude more abundant. Despite this, it continues to increase, and had its best year on record there in 2020. Indeed, it is now a relatively common sight in gardens in some core areas later in the season, where it feeds on verbena and buddleia alongside other species of white.

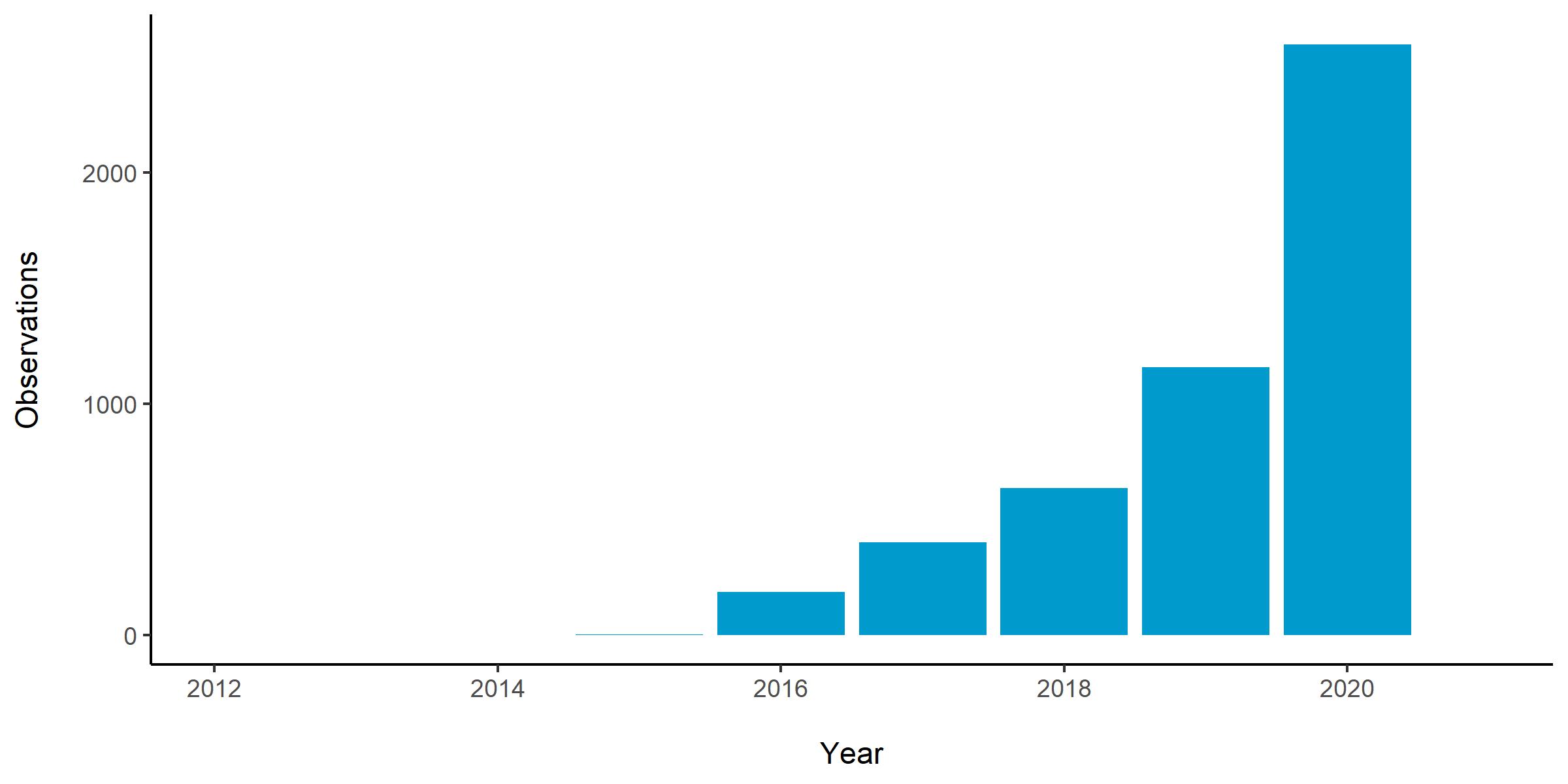

Observations of Southern Small White in The Netherlands by year, showing a remarkable increase after the first records in 2015. Data from waarneming.nl.

This apparent fondness for urban areas has been a noticeable feature of the rise of Southern Small White. In Switzerland most new locations were rockeries and steep, terraced gardens where Perennial Candytuft (Iberis sempervirens) is grown. This has continued to hold true as it has spread northwards, and breeding is most often confirmed first on this plant in new areas. Whether this impression represents a genuine preference for Perennial Candytuft over other crucifers the species is known to use, and real benefits from warm urban areas, or is just a result of where most observers are concentrated and looking for the species is not totally clear.

Although suitably warm, rocky areas for Southern Small White may be rare outside of urban areas, it seems possible that it may have been making more regular use of crucifers other than Perennial Candytuft as it has spread north, perhaps around sheltered, disturbed areas like brownfield sites, embankments and quarries. Tristan Lafranchis lists 20 different foodplants for Southern Small White, some of which are common in the areas it has recently colonised. In the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, for example, searches away from urban areas have revealed that colonies seemingly based on Wild Rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia) are relatively frequent, and in a small choice experiments with females choosing between this species and Perennial Candytuft, the former was strongly preferred. Similarly, in The Netherlands the butterfly is also thought to be using the small amounts of cultivated rocket grown in vegetable gardens. This plant is also widely cultivated in the UK, while Wild Rocket is a historic and relatively widespread introduction, occurring on rocky waste ground and railway embankments, particularly in south-east England.

Urban habitat (centre) of Southern Small White in Sint Martins Voeren, Limburg, with abundant Candytuft; and its life cycle, starting with a mature egg (top left) and going clockwise to the first instar and second instar larvae (with distinctive dark heads), a mature larva (of andegeva) and the pupa (Pieter Vantieghem).

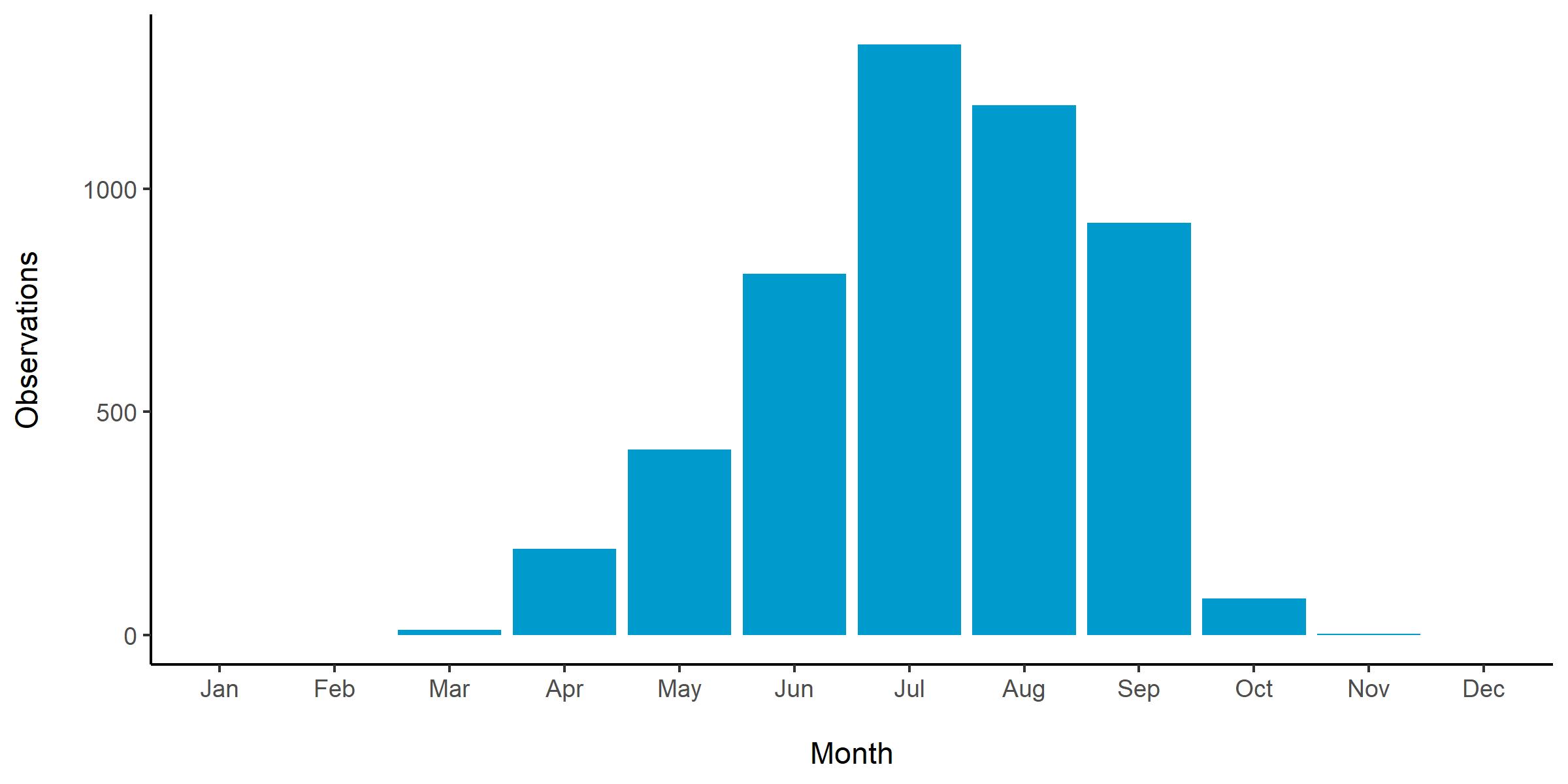

Eggs are normally laid singly on the underside of the youngest leaves, turning yellow as they develop and hatching after four to five days in a warm location. The young larvae also stick to the underside of the leaves, where they are well-camouflaged and can be separated straight away from other Pieris species on the basis of their dark brown-black heads in the first and second instar before turning paler green (as seen in Small and Green-veined White) as the larvae develop. The pupa (the over-wintering stage) varies from grey to green, depending on the substrate, as is typical for Pierids. In regions where Southern Small White is present, most of these stages can be found at the same time in the later part of the season, as the butterfly can have several broods a year, with considerable overlap between them. In southern Germany, five broods have been recorded (as early as mid-March and as late as early November), while in The Netherlands, four currently seems to be typical. It is the larger, later broods that seem to be more prone to dispersal in late summer, appearing in new areas from July onwards before being seen in numbers the following year as the butterfly continues to spread north. It is likely that if (or when) Southern Small White makes it to the UK, it will be at this time of year.

Records of Southern Small White in the Netherlands by month. Data from waarneming.nl.

With no sign of its expansion slowing down, the butterfly's arrival here does seem increasingly likely. It has already proven itself capable of crossing large areas of unsuitable habitat, and indeed water, with a record from Vlieland (the northernmost Dutch Wadden Island) in 2020, 25 km north of the Dutch mainland. The shortest distance across the channel from Calais (where it was recorded in 2019) to Dover is only a fraction further, at just over 30 km. This may not be the route Southern Small White takes though, as it remains relatively scarce or at least under-recorded along the Channel coast, as its direction of travel has been mainly northerly along the Rhine to the Low Countries, with relatively little diffusion out east and west. Thus, a crossing from the stronger colonies in the Low Countries that arrives further up the east coast may be just as likely.

Identification

Inevitably, for any initial claims of Southern Small White in the UK to hold water, they will need to be well documented, to eliminate the possibility of confusion with Small White. The two species look extremely similar, and identification relies on a combination of features, many of which are prone to vary with season and location. While these are usually enough to identify most specimens, even experts struggle with some, and perhaps the only truly 'safe' feature for separating the two species is the clear difference in the head colour of the young larvae.

A typical late-summer female Southern Small White with heavy dark markings (Pieter Vantieghem).

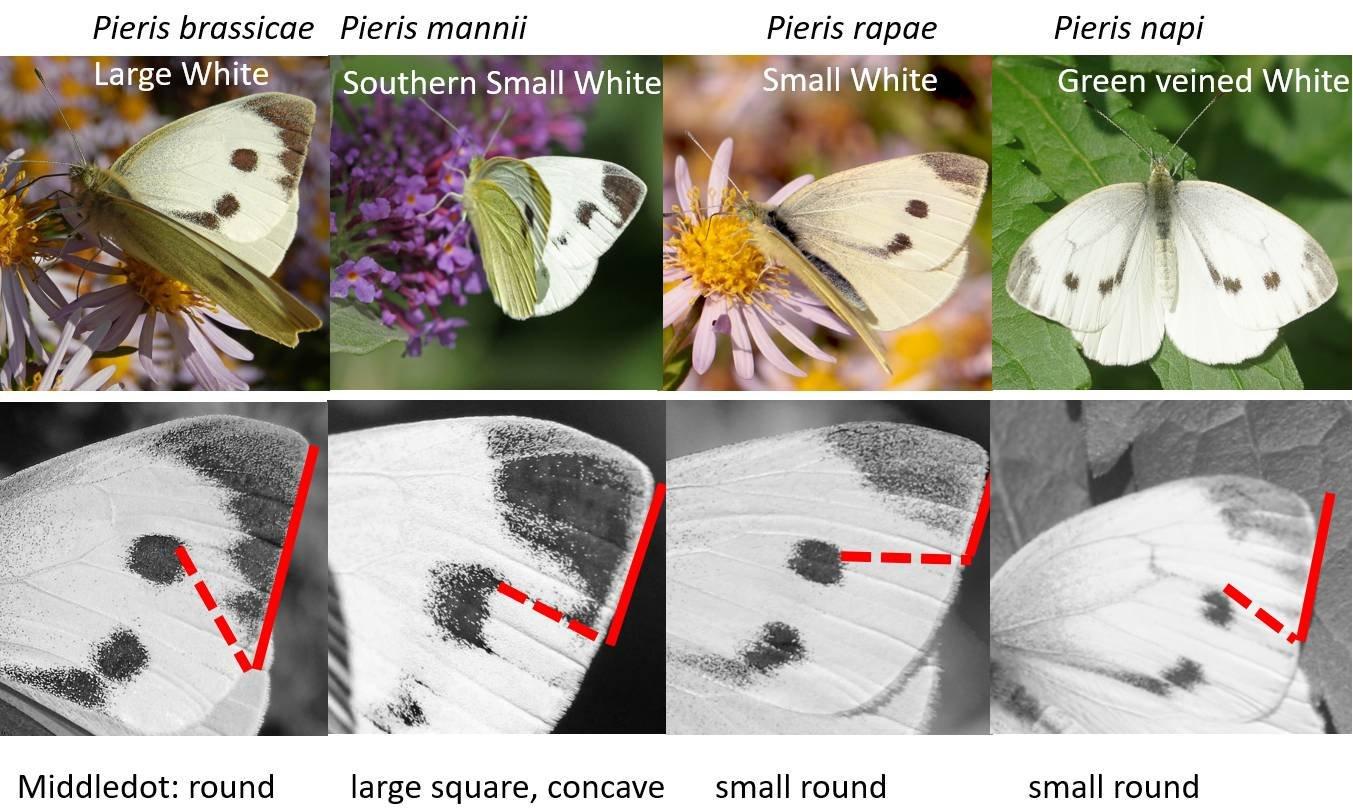

Broadly speaking, Southern Small White (SSW) is a rounder butterfly than Small White (SW), with more extensive black markings. The key features for separating them are illustrated in detail on Lepiforum, and consist of the following:

- Apical spot: In SSW this usually extends further down the outside edge of the wing, almost always reaching the upper discal spot. On the other hand, in SW, this spot usually ends well above the upper discal spot. Essentially, if you draw an imaginary line between the discal and apical spots in SSW it's horizontal, and in SW it runs upwards.

- Discal spot: The outer edge of the upper discal spot is straight or concave in SSW, but normally more rounded in SW and almost always limited by the upper and lower vein. The spot is also generally bigger in SSW, often spilling out of the veins and linking to the bottom of the apical spot by black scales along them.

- Shape: SSW usually has a more rounded forewing apex.

- Hindwing features: Many female SSW (especially in summer) have a small discal spot in middle of the hindwing, which is very rare (except in some aberrant specimens) in SW.

- Venation: Some authors state that SW has a fork in the apical vein (V7) that SSW lacks, but others now consider this feature to be unreliable, as some specimens of SSW can show this feature.

Spot patterns on Southern Small White and our common native whites. On Southern Small White the apical spot extends further down the wing in line with the heavier upper discal spot than in Small White (Chris van Swaay).

It is important to note, however, that these features are prone to individual and seasonal variation. In both Small White and Southern Small White, dark markings tend to be more extensive in summer specimens than spring ones. This means that summer Small Whites in warm regions can show extensive apical spots, with black marking extending as far down the wing as the upper edge of the upper discal spot. Similarly, the upper discal spot may be more rectangular (but still limited by the veins) in summer Small Whites, and more weakly marked and rounded in the first generation of Southern Small White. Furthermore, summer females of Small White may also have quite rounded wings in warmer regions. To reach a firm identification then, these features should not be used in isolation, but in combination, with a clear understanding of the copious variation of the commoner Small White.

With this approach, it should be possible to identify most specimens with confidence. If you think you've seen one, Butterfly Conservation will be keen to hear, and you can email southernsmallwhite@butterfly-conservation.org to consult with experts that are familiar with the species. Greenwings Wildlife Holidays is also offering a beautiful limited edition Richard Lewington print of the species to the finder of the first Southern Small White in the UK, a fantastic incentive for what would already be a remarkable prize for any lepidopterist.

Find out more

Useful literature on Southern Small White

Tristan Lafranchi's bibliography on Southern Small White provides a useful list of European literature on the species and its expansion up to May 2020 (although much of this in in German).

For a useful English summary, Pieter Vantieghem's article on the butterfly's appearance in the low countries is excellent: Vantieghem, P. 2018. First sightings of the southern small white Pieris mannii. (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) in the Low Countries. Phegea, 46: 1, 2-7.

Pieter Vantieghem and Chris van Swaay of De Vlinderstichting also post regular updates on the progress of Southern Small White in the Low Countries on twitter, and both kindly provided photos and suggestions for this article.

Track its expansion in real time

Various European citizen science platforms provide you with the option of tracking the butterfly's expansion in real time. The two Waarneming sites are particularly well-used.

waarneming.nl – for records in the Netherlands.

waarnemingen.be – for records in Belgium.

observation.org – for records from across Europe.

www.inaturalist.org/observations?taxon_id=336700 – iNaturalist, increasingly used across Europe.