In the summer of 2007, BirdGuides contributor Graham Gordon went on an extended three-month birdwatching trip to Ecuador and Peru. Previously on BirdGuides, we have read tales of journeys to see Diademed Sandpiper-plover in the Peruvian Andes, and exciting antpittas in the cloud-forests of both countries. This third article concerns Graham's attempt to see one of the rarest hummingbirds in the world, the Marvellous Spatuletail, and provides short notes on several more exotic hummingbird encounters along the way.

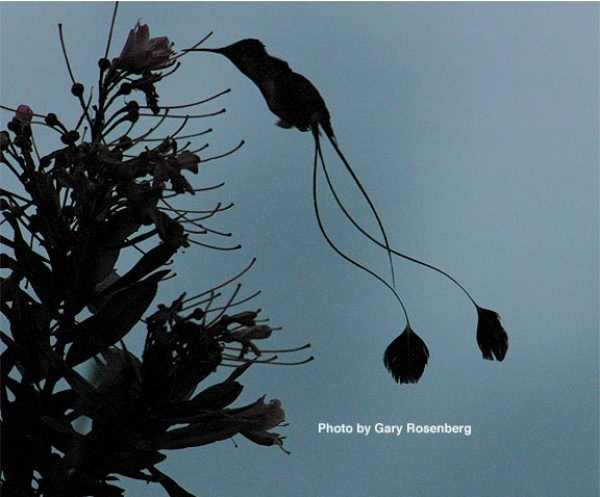

Marvellous Spatuletail one of the rarest and most spectacular hummingbirds in the world (photo: Gary Rosenberg)

As a general rule, I must admit, I wouldn't normally be found trying to seek out someone to show me birds when I'm on an overseas trip. It's less a question of cost and pride than simply the fact I enjoy my birds that much more when there's a sense of self-discovery about them. I can't remember a time when I didn't feel that way. But needs must, and on this occasion I found myself practically begging for someone to take me and show me that which I had failed to find on my own.

I had journeyed to the little town of Pomacochas on my route through Northern Peru. This is the only area in the world where a particularly spectacular endemic hummingbird, the Marvellous Spatuletail, is known to occur. As well as the Diademed Sandpiper-plover I wrote about earlier (see here), the seeds of my determination to see Marvellous Spatuletail were planted many months before my trip to Peru, based in part on stories from friends who had already seen it. Soon after my arrival in town one afternoon, I had jumped in to a motorcycle taxi, and chugged the 6 kilometres west, back down the road to a site for the Spatuletail described in Thomas Valqui's Where to Watch Birds in Peru. Valqui offered some very specific advice about the types of flowers the Spatuletail was usually found on, and gave six or seven different spots in a small area in which to look. Armed with a copy of this guide, and a statement to the effect that 'the bird can often be found within the first thirty minutes of arrival, sometimes right next to the road,' I set off with great confidence, binoculars at the ready.

Forty-eight hours later, I still hadn't seen one! It appeared the Romero plants the bird favoured were not in season. I'd alternated climbing up and down steep hillsides with sitting patiently in one spot for hours at a time, at first expectantly, then hopefully, and then finally, desperately. I was reduced to a glum resignation. Marvellous Spatuletail was much too highly prized a bird to go without, in my estimation. I would have to resort to Plan B.

I'd been told by one of my contacts, Roger Ahlman - a Swedish birder living in Quito, Ecuador - that I should try to find Señor Montenegro in Pomacochas. "If you fail to find them yourself, he's your man. He'll take you direct to the Spatuletails. He knows a place where they lek."

And now here was this Señor Montenegro, sat in my hotel lobby, discussing plans for the morning. I'd found him by a convoluted route of enquiries in town that had seen me travelling to at least four different establishments before finally nailing him down. "Ah, my friend, Roger!" he exclaimed. "Yes, of course, no problem, I can take you out tomorrow. Roger always comes with me on his bird tours. Sometimes I go all day, sometimes half day. Always he has American birdwatchers, English, Australian. We go to Abra Patricia; I stop; I show you where to go..."

"Yes, but can you show me Marvellous Spatuletail?" I insisted, cutting straight to the chase. I already knew about Abra Patricia, a cloudforest site an hour to the east: a selection of endemic antpittas, yet no Spatuletails to the best of my knowledge.

"Si, si, no problema!"

Now, I was still a little out of my depth with the Spanish language, even now, six weeks into my trip. But no problema is no problem, isn't it? We all understand that. So why was I harbouring just a teensy bit concern when I lay my head on the pillow that night, worried that all was not quite what it seemed? Just a bit of pre-match nerves, eh? In the main, I think I'm fairly relaxed about my birding, but just every now and again some bird or other can still wind me up to a highly strung coil. And Marvellous Spatuletail was doing that right now. Maybe I should have negotiated a fixed price when I had the chance? No, I thought, that wouldn't have been in keeping with the occasion. I wanted to see Marvellous Spatuletail and I'd worry about cost once I'd seen it.

Misty mountain tops, northern Peru (photo: Ian Puckrin)

I was a bit concerned when Señor Montenegro turned right at the T-junction at the top of the road early next morning, when in my mind I thought we should be going left. I was more concerned when we kept driving for thirty minutes, forty-five minutes, an hour.... Surely we were getting outside of the Marvellous Spatuletail's very limited range by now? I continued to try to make small talk with my driver, a chance to practise my Spanish, but something had snapped inside: a brooding unease had set in. Still our different languages left gaps in our full communication with one another. When we stopped the car at Abra Patricia and Señor Montenegero waited for me to make the first move, I knew something had gone badly wrong. I'd heard about charlatans making a living from deceiving innocent birders - yet this bloke clearly knew Roger Ahlman alright. "Ah, my friend Roger," he kept saying. "He's a good man, brings me many tourists."

I stated my case as clearly as I could in a language with which I was most unfamiliar. My twitching fever invaded my brain and muddled my phrases.

"Do you or do you not know where I can find Marvellous Spatuletail!" I demanded, most ingenuously.

Señor Montenegro pointed back the way we had just come and bowed his head.

"So what the bleepity-bleep-bleep-beep are we doing here!" I roared...in Spanish!

We turned the car round and drove back the way we had just come. Wearily, I asked if we could stop at Restaurant La Chachita for a coffee, and also because I needed to ask if I could stay on their floor for a couple of nights. This was the area where I would go on to see several of the antpittas I mentioned in my previous BirdGuides story. As luck would have it, there was a tall, fair-haired figure stood outside the restaurant, wearing, of all things, a Marvellous Spatuletail sweatshirt! It was Greg Hummell - a Californian birder and one of the few Westerners I'd encountered so far on this trip. Greg was able to offer me some crucial, up-to-date information on my quarry: he himself had found and filmed a Marvellous Spatuletail lek a week earlier just 50 yards down the road from where I'd spent the last two days looking...

There was a tense silence in the car as Señor Montenegro drove me back to Pomacochas, onwards through town, and direct to the spot Greg had advised me to start searching. As we passed through the town, he remarked casually: "Have you thought about finding Santos Montenegro? I believe he has some Marvellous Spatuletails (Colibri espatulla he called them) nesting on his land..."

There was a stunned silence for a moment and then the penny dropped. I'd got hold of the wrong Señor Montenegro. How was I to know there would be two gentlemen of the same name in this tiny little town! Everything had seemed to add up - Señor Montenegro: a taxi driver and bird guide who knew Roger Ahlman - until we'd taken that right turn out of town. My main problem now was: how much was this going to cost! This guy had thought I was some rich American bird dude who wanted an all-day taxi to himself; instead I was a cheapskate hardcore birder who'd just wasted three hours' precious birding time going in completely the wrong direction to where he wanted to be. Twenty-five dollars was just about my budget for a day: accommodation, food and all. "If it's less than twenty-five I won't make an issue of it," I thought to myself. He wanted sixty!

And so began my first-ever argument in Spanish. Fortunately, I knew the word for misunderstanding - un malentendido - because that's exactly what it was: we had an honest discussion, I got the price down to thirty, we shook hands and he drove off. I turned around to start birding. And a Marvellous Spatuletail flew right past my nose. You may already be wondering, if you don't know the bird, why all the fuss about Marvellous Spatuletail? So let me explain.

First let me start with hummingbirds in general. I've written about hummingbirds before on the BirdGuides web pages, and while I'm not going to repeat everything I said there, I'd like to reiterate one or two points, if I may. Where once upon a time it might have been the Calidris waders and Phylloscopus warblers that provided me with my first glimpses of Infinity - followed later by the American Dendroica warblers - for the past ten years, it has been the hummingbird family that have provided my deepest insights into the Wonder of it All. A friend of mine once suggested that watching hummingbirds in action was so unlike any other birdwatching experience he could well believe they'd come to Earth from another planet, perhaps arriving on a fallen meteor! I looked for the twinkle in his eyes to suggest he might be joking, but I really think he was quite serious. Whether fanciful or not, it's a nice thought anyway.

My first experience with South American hummingbirds was at the British-owned Bellavista Cloud Forest in the northwest of Ecuador in February of 2006. Here, and in the surrounding Tandayapa Valley region, are about 50 of the world's 337 different hummingbird species, leading more than one rapt birder to describe the area as 'the hummingbird capital of the world'. At Bellavista, my friends and I saw about 16 different species all at once, buzzing back and forth from the sugar-water filled feeders that are now a feature of many ecotourist lodges the length and breadth of Ecuador. I wrote last month about the joys of chasing after skulking forest ground-dwellers in these wet Andean forests, and I know some birders still prefer the challenge of tracking down hummingbirds away from the feeders, but to me, they provide a whole different dimension of experience, where one can sit back, relax, and remember that we were all once birdwatchers before we became birders.

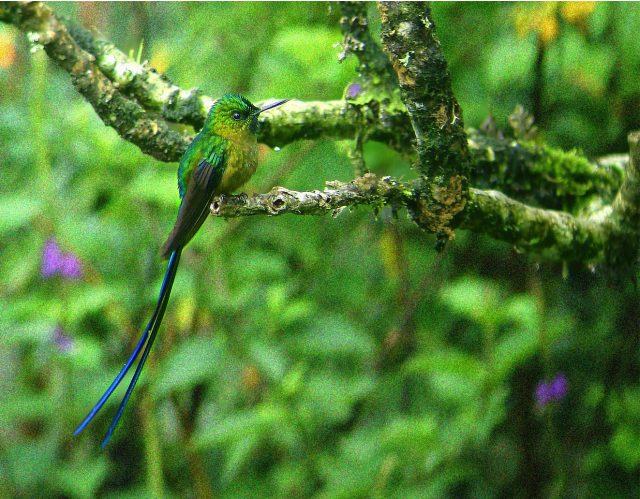

I'll throw out just some of the names of the birds we saw at Bellavista and in the surrounding area, to illustrate one particular point about hummingbird watching: Velvet-purple Coronet, Green-fronted Brilliant, Long-tailed Sylph, Purple-throated Woodstar, Western Emerald, Booted Racket-tail, Purple-bibbed Whitetip, Black-tailed Trainbearer, Gorgeted Sunangel, Sparkling Violetear. Aren't they just amazing names to roll around your tongue and to savour! You don't even have to know what these birds look like to allow your imagination to roam freely in my opinion - one of the primary attractions of the family. Imagine up to 40 or 50 different individuals of a dozen or more species buzzing around your nose from the first break of dawn to the last rays of light, heavy rain or sunshine, and you have another reason to delight. Such a spectacle now exists in dozens of locations throughout northwest Ecuador, at several sites on the Andean east slope, and again, in a number of places in the south.

Booted Racket-tail tiny and endearing (photo: Paul Derbyshire)

Purple-throated Woodstar at the Bellavista feeders (photo: Paul Derbyshire)

Imagine too, in more than one of these locations, especially around the extraordinary little village of Mindo, not far from Bellavista, you can sit there with a cool beer, or a fresh-squeezed fruit juice, or a frothy mocha coffee, and watch these birds back and forth all day, and you are transported to Heaven on Earth. I became familiar over two different trips to Ecuador with one particular restaurant in the village of Mindo called Los Colibries - Colibri being the Spanish word for hummingbird. There, my friends and I used to lounge throughout the afternoon, watching White-necked Jacobins, Green-crowned Woodnymphs, Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds, Green Thorntail, White-whiskered Hermits, Brown and Collared Incas, marvelling at their jazzy colours, various head and tail adornments, and their astonishing mastery of flight: now hovering at 90 wingbeats a second; now dashing off in the split second of the blink of an eye; feeding, fighting, chattering, squabbling; or sometimes just sitting there, preening or bathing, or waiting for their turn to have a chance at the feeder. When I returned to Ecuador in May of 2007 it just so happened a party of 48 people were passing through for lunch, and seeing the restaurant was short-staffed, I jumped at the opportunity to help out. A tiny Booted Racket-tail came in under the canopy and buzzed me around the ear as I attempted to serve a dish.

Long-tailed Sylph a north-west Ecuadorian speciality (photo: Paul Derbyshire)

Such intimate close contact with hummingbirds is an occasional feature of birding in the high Andean cloud-forest, away from the feeders. Several years ago, while volunteering as a guide for the Cape May Bird Observatory, I was presented with a snazzy scarlet red jumper to mark me out as an 'official.' It's an embarrassingly naff thing to wear in the more sombre setting of a British or Irish context, but it has somehow found its way into my luggage on three separate voyages to the Neotropics. On more than a dozen occasions I've seen hummingbirds in hundred mile an hour flight, break instantly to a standstill, turn, and make a bee-line direct towards my midriff. Only their astonishing braking capacity seems to prevent them piercing my insides with their needle-fine bills. At one site in southern Ecuador I had three Chestnut-breasted Coronets buzz me in this way for a full thirty seconds, while a Fiery-throated Sunangel sat on my arm! Some birdwatchers in South America wear a flower in their hat to achieve the same effect.

Chestnut-breasted Coronet reasonably common at some sites in the Eastern Andes (photo: Simon Plat)

And then there's the Sword-billed Hummingbird! Maybe you've seen it on the telly? Who can fail to be amazed at this bird with a bill longer than its body? I've only encountered a handful of individuals on my travels, I have to say, but I will always remember my first: a bird at the feeders at Guango Lodge on the central Andean plateau of northern Ecuador. I was in the process of trying to negotiate permission for my friends and me to enter the lodge garden when this thing appeared right next to me, completely interrupting my train of thought when searching for the appropriate Spanish verb to explain our purpose in being there. I just stood there, goggle-eyed and slack-jawed and the landowner smiled and bid us enter.

I was similarly gob-smacked by my first encounter with the Giant Hummingbird of the dry, central Andean valleys. It's a fairly widespread species, but nowhere particularly common. I'd checked into a hotel after a full day's coach travel, and I just popped out for an hour in late afternoon to stretch my legs. I was in a largely unbirded area of central Peru, so I had no idea what to expect when I set out into a rather cartoon-like, cacti-encrusted canyon (think meep-meep The Roadrunner!). Within minutes this all-dark brown, almost Leach's Petrel-sized and shaped hummingbird appeared, hovering slowly (compared to the rest of its family) in front of a multicoloured collection of desert flowers - the largest hummingbird in the world.

I wish I had room to tell you more about the Wire-crested Thorntail, or the Rufous-crested Coquette, or elaborate on perhaps my favourite of them all, the Collared Inca, but already I fear I've strayed too far away from my tale of the Marvellous Spatuletail.

Rufous-crested Coquette another gorgeous little hummingbird that is high on most people's wanted list for Peru. I saw it in the northern lowlands at Morro de Calzada (photo: Simon Woolley)

So there I am, by the side of the main road on the highway linking the Andean towns of northern Peru to the Amazon lowlands. It is a route that is important to the Peruvian government for economic reasons: many goods are shipped through to Brazil along this road, and for that reason it is one of the few roads in Peru away from the main cities that is covered in tarmac. I say this in the context of my current account because I've just finally got on to my first Marvellous Spatuletail after two and a half days of searching, when a huge 40-ton articulated lorry grinds noisily past me up the hill and that's the end of that sighting.

Eventually, half-an-hour later, I get my first glimpse of a spectacular male Marvellous Spatuletail on the opposite side of the road, and I recoil back into the grass verge to prop my binoculars up and lie and watch it. I manage about ten seconds' distant viewing before, again, another huge lorry comes, covers me in fumes, and sees off the Spatuletail in the process. This goes on for about an hour. There are certainly plenty of breaks in the traffic, about one lorry every five minutes, but the hills are so steep here that when a truck does come, its passing takes at least a couple of minutes. At one point, I got thirty seconds' uninterrupted viewing of a male Spatuletail at a reasonable middle range and that, I thought, was where the story would end. I decided that would have to 'do', and now maybe it was time I moved on. It was a nice occasion to be here, but after all the expectation I'd built up, a touch anti-climatic, if I'm honest.

By and by, a mototaxi - a small motorbike with a sort of sedan chair on the back - spluttered to a halt at the side of the road, and its single occupant got out and started ambling slowly towards me.

"Oh, go away," I thought to myself, "I can't be bothered with conversation at the moment." I was in a small private cocoon of my own right then: part pleasure at the capture at last of a Spatuletail sighting and part relief, it must be said too. But I was also feeling a bit worn down being the only gringo in town; it was all very well saying Hello and Good Morning/Good Afternoon a hundred times a day, but if I was in need of any company at all it was company and conversation of a strictly birding nature I felt like. I wasn't in the mood for any more polite small talk after my emotionally taxing encounter with Señor Montenegro this morning.

"Hello," said the mototaxi rider. "I am Santos Montenegro. I believe you have been looking for me?" News travels fast in these small Andean towns.

"Ah, meester Montenegro, we meet at last," was the first thought that came into my mind, and I immediately relaxed and smiled, and shook the man's hand warmly. The guy had, after all, ridden four miles to see me.

I explained all that had happened that morning. Santos, in turn, confirmed he had a Marvellous Spatuletail lek on his land, and that he wished he could have taken me to see them.

"But now I see you have already seen the Spatuletail," he said, indicating the opposite hillside. "I am pleased for you. I will go now and leave you with your bird. Goodbye."

He turned to walk away.

"No, no," I called after him. "Please, come back. I would really like to see your birds, too. When can we go there?"

"Tomorrow morning. I can collect you at your hotel at six-thirty, if you like?"

What a pleasure it was to go out next morning with this guy. If you have travelled overseas, and have had occasion to meet some of the, shall we say, more unscrupulous or desperate types who try to cheat you out of your money, you will understand that not all bird guides are what they claim. But this guy was an absolute gem. When I tried to fix a price he just said: "Don't worry, I don't ask for money. If you want I will take you for nothing. But if you feel like it, you name your price, I don't mind." I can't remember what I gave him in the end, but for what I went on to experience, it was very little really. In fact, to put a value on how much I enjoyed walking with Santos in the hills behind his house, high above the road...well, I could have given him all my life-savings and it still might not be enough.

Only a few species of hummingbirds, to my knowledge, seem to form leks, where several males congregate to do battle with one another. The Hermit Hummingbirds - for example, Green and Great-billed - certainly do. At first I heard these persistent, quite annoying little insect-like noises going on all morning in two separate patches of rainforest earlier in my trip, and it was only very late I discovered that they were male Hummingbirds: monotonously calling from the same perch, and just occasionally flying out for a quick wrestle with their neighbour. I saw the same male Sparkling Violetear three days in a row sat on the same perch on the Manu Road in central Peru doing the exact same thing.

There are thought to be no more than 200 pairs of Marvellous Spatuletail in the World, a distribution covering a very small area of northern Peru. They are hugely threatened by ongoing deforestation. In the year 2000, Santos Montenegro found the only known lek of the species, and just recently, ten days before my arrival in fact, Greg Hummell found the second. Such was the significance of my march into the hills with Santos on this particular morning.

I was a bit out of breath when we came to the top of the hill. I was glad when we stopped. "See that bush there?" whispered my companion, checking his watch. "Five minutes...there'll be a Marvellous Spatuletail there."

Such confidence!

But he was right. At eight o'clock, more or less on the dot, an adult male Marvellous Spatuletail came in and sat there preening for fifteen minutes. Though the accompanying photographs will reveal to you what a Marvellous Spatuletail looks like, I shall say a few words to add to the picture. The male Marvellous Spatuletail is unique in having only four tail feathers: two of these, the central tail feathers, are relatively short and pointed; the outer tail feathers, from which the bird derives its name, seem impossibly long for such a small bird, and are thin, wiry and flexible, culminating in a flat club-shaped pennant. The male I was watching continued to fine-tune its feathers for the display.

Marvellous Spatuletail preparing to display (photo: Roger Ahlman)

And there it was: the first rival male turning up to wage war; an immature male this second bird, its tail feathers shorter and less spectacular than the adult, and the iridescence of its plumage less pronounced. The scene was pure television documentary come to life in the dramatic setting of these Peruvian hills. In display, and in territorial fights such as this one, the male Spatuletail is able to twist its remarkable outer tail feathers such that they stand vertically above its head. The bill is pointed towards the sky as it hovers on the spot in front of its rival, pencil-thin, and the two set off on a remarkable 'dance', embarking upon a quite extraordinary aerial battle of forward, backward, and sideways manoeuvres, practically impossible for the human eye to predict. If there really are such things as UFOs, and anti-gravity technology is possible, then here is a preview of what it will look like!

I watched this scenario play out for another twenty minutes. A second rival immature male appeared to dispute the display perch, and briefly, another full adult. Santos tapped me on the shoulder and whispered: "Look behind." He was pointing to a spot where, rather distantly, I could see a brief exchange between two smaller hummingbirds. "That's the female Spatuletail feeding one of this year's chicks," he told me. He motioned me follow for a closer look, but in an instant the birds were gone. A little later, he was able to show me the nest they'd used a month or so earlier: a tiny structure of dried grass hidden away in amongst some heather-like plant close to the ground. All this was a far greater glimpse into the bird's biology than I would have had if I'd settled for the tick-and-run views I'd had yesterday.

My conversations with Santos were conducted quietly in Spanish. We talked about the hummingbirds he had seen in the area, and he surprised me by telling me he had travelled to see the Jocotoco Antpittas in Ecuador. I'd thought of him as a simple family man plying a trade as a mototaxi driver in this remote region of Peru, but he was clearly quite a budding young twitcher. It was at least two days' travel to get to the Jocotoco site across the border in southern Ecuador, far more than the distance I remember from Newcastle to Cornwall. When Santos spoke, even though he talked slowly and distinctly, I sometimes had to concentrate hard to understand him. I was still in the process of trying to translate my Spanish from the exercise book to practical reality. There was a moment of comedy when Santos said "Banos" and I trotted after him thinking we were off to see the Hummingbirds at their morning bath. "No, no, banos" he insisted, and I smiled and nodded and continued to follow faithfully close behind. Then it suddenly dawned on me he was telling me he was off to use the bushes as a loo and I sheepishly about-turned and allowed him his privacy!

Santos had to go to work. He bid me goodbye and set off down the hill while telling me to take my time and spend as much time as I wanted on his land. His land, I could see, high above the main road where the occasional lorry could still be seen way off below, happily out of earshot, was a beautiful, fragile area of ferns and brackens and various alpine plants, interspersed with the odd patch of bushes such as the ones in which I returned to watch the Spatuletails at my leisure. It was nine o'clock. I was very tempted to leave there and then with Santos, having missed my usual early-morning caffeine fix. But something stopped me and turned me back round after just my first couple of footsteps. This was too good an opportunity to turn my back on: it was time to sit down and take stock.

I sat on a comfortable rock about fifteen yards from the Spatuletail perch. On my own, it was tempting to want to inch ever closer forward, but I curbed my instinct and settled instead for a relaxed meditation in the slowly rising sunshine, keeping just one eye on the activity across the way. Suddenly, even to the naked eye, there was a commotion of activity at the perch. Binoculars revealed four males: two adults and two immatures battling for supremacy, twittering and vibrating, snapping their wings. Then, as if drawn by my will, the two adult males worked their way inexorably towards me, low to the ground, dancing and calling. Up until this time, the males' posturing had lasted a mere couple of seconds: here, the joust entered its third minute. It was a display of elfin elegance as outlandish and breathtaking in its own way as any Bird of Paradise, and it was now happening about three yards from my knee! It was one of those rare subjective encounters with the Natural World when you feel so utterly privileged to be the observer at the scene, that you can't help feeling the show has been staged solely for you! All the frustration of that initial fruitless forty-eight-hour period evaporated in an instant. It was as though even that was an integral part of the warm fuzzy glow that enveloped me now; this wouldn't have happened without it.

When the show ended, and the birds disappeared in a flash, I got up and staggered off, grinning inanely. What I would give to be in this mood at all times! Anyone coming up the hill and encountering me at that precise moment would have seen a madman: arms aloft in praise to the skies, chuntering and laughing away to himself. Get in, you little beauty! I love Hummingbirds, I do.

Marvellous Spatuletail on its display perch; tail feathers halfway to position above the head, where they will shake and vibrate as the bird engages in dispute with others of its kind (photo: Roger Ahlman).

Thanks to the photographers who lent me their pictures for this article: Gary Rosenberg, Paul Derbyshire, Ian Puckrin, Roger Ahlman, Simon Plat, and Simon Woolley. If you want to see actual footage of the Marvellous Spatuletail’s lek display, a short but spectacular video by Greg Hommell is available at nationalgeographic.com.

If you wish you can contact Graham by email, click here.