How lucky are we to have a pastime in which the soundtrack is birdsong? Right now, with spring gathering pace and summer visitors pouring back in, the skies are filling up with of the most arresting chorus, and it is likely that many species first make it onto your year list courtesy of your ears.

Birdsong has played a large part in my life. Raised by birding parents, my dad was – in his spare time – the volunteer warden of a woodland nature reserve where Common Nightingales bred. Every year in early May, he would guide groups of people to listen in reverential silence to the free concert, and from an early age I'd tag along.

Common Nightingale was one of the species that got Adrian Thomas hooked on birdsong (Dean Eades).

I've remained captivated by birdsong ever since. I love how birds look, but their sounds seem to convey something more primal, more resonant of place and season. And I love how generous birds are with their vocalisations. How many birds would go unrecorded if it wasn't for them revealing themselves with a burst of song or quick call? The question isn't entirely rhetorical: I suggest the figure could be at least 80 per cent in summer woodland.

However, while some birders seem to have superhuman ID ability when it comes to bird sound, for others (and I include myself in that) the skill isn't necessarily as well-honed. The Sound Approach team has done amazing things at the expert end of the spectrum, but I wondered whether more could be done to help mere mortals such as myself?

After mulling it over for years, I finally took the leap in 2015. I bought a parabolic microphone and recorder and set out with tent and notebook to see what I could produce. Four years later and I've got something to show for it: the RSPB Guide to Birdsong – we'll see if it helps!

There were two areas I really wanted to focus on. Firstly, whether we can improve our ability to describe sounds, to articulate what we hear, which feels weaker and less assured than our visual vocabulary.

Secondly, I'm a big fan of the learning techniques you find in foreign-language courses. There, you get text, images and audio guidance rolled into one, and I wanted all those elements to be present. I like to be able to take things step by step, I benefit from having visuals to consolidate my learning and I like to test myself along the way.

So the book contains an audio guide (CD/digital download) and comes in three sections. In part one, I explore ways to describe sounds. In particular, it can be much more manageable to focus on different attributes of a sound, one at a time, rather than try to take in the whole thing in one go.

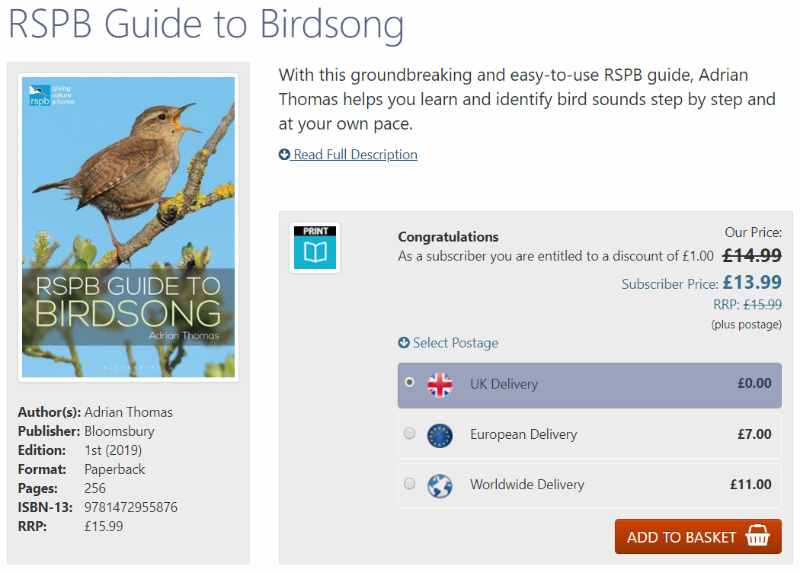

The seven attributes I think are most useful are duration, pace, volume, pitch, pattern, timbre and overall effect. Duration, for example, is about listening to how long an individual note or song verse lasts. There's plenty of variety, from the short 1-1.5-second verses of European Stonechat song to what seems an epic 6-8 seconds of Eurasian Wren's, but then a Dipper's verse often lasts 10-30 seconds, while at the ‘when do they manage to breathe?' extremes are Eurasian Skylark and Grasshopper Warbler.

Duration can also apply to the gaps between song verses; Garden Warbler often leaves much shorter pauses than Blackcap. And as an example of the length of individual notes, the 'bee' notes of Marsh Tit call (chicka-BEE BEE BEE) can seem almost as peeved as those of Willow Tit, but the latter's tcharrr notes are about twice as long.

A spread from Section 1, exploring one of the attributes to focus on: pace.

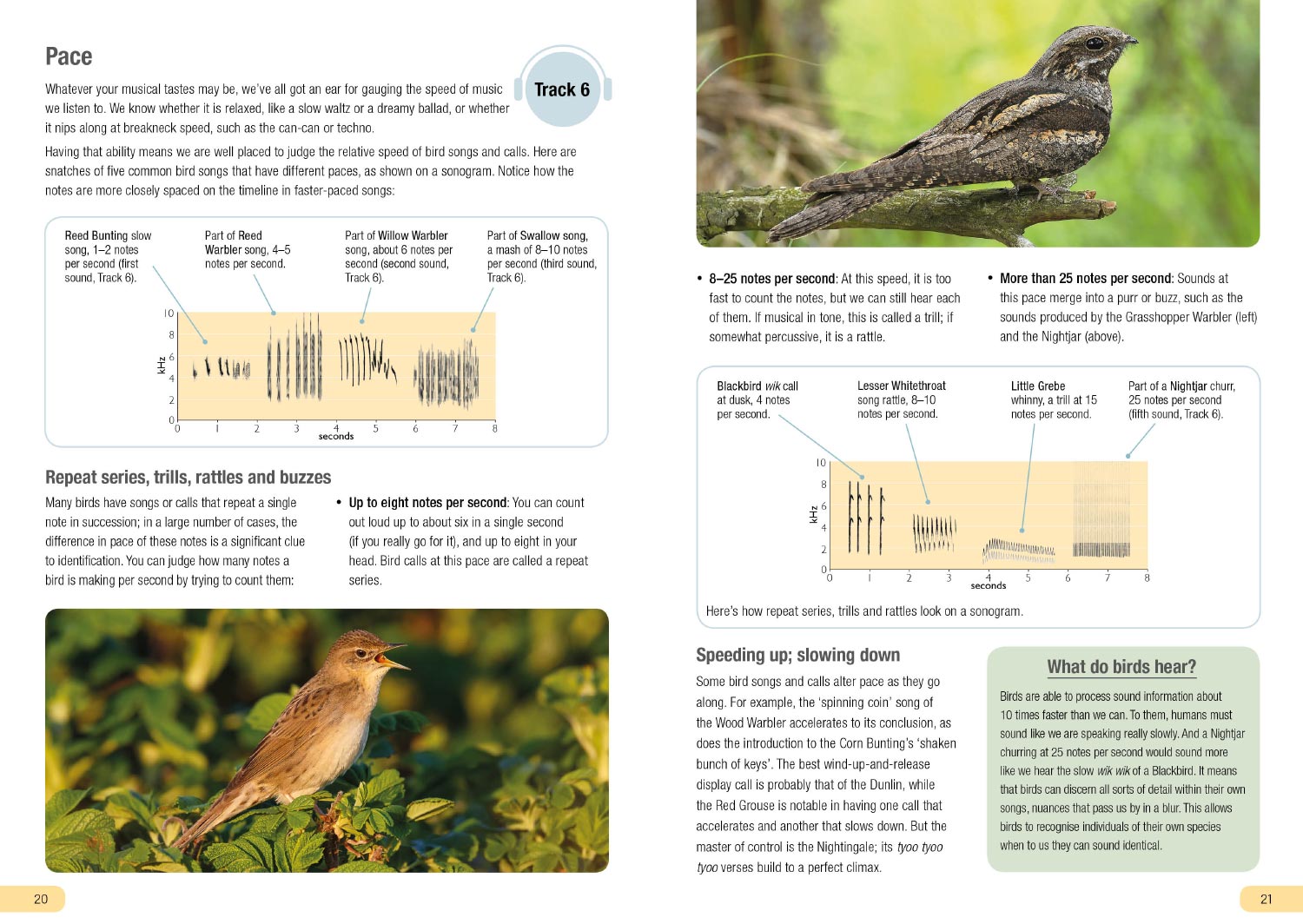

Part two runs through 65 of the commoner garden and countryside birds, focusing on those which tend to be heard as often as seen. After every few species, there is a 'test yourself' section. While I felt very familiar with all these sounds, it has been fascinating to revisit them with open ears. How does Blackbird song really differ from Mistle Thrush? Or Carrion Crow calls from Rook? These common bird sounds are our foundation for learning all other avian vocalisations, and I'm hoping that even experienced birders will get value from listening to them afresh.

A spread from Section 2 which, like Section 1, runs in tandem with the recordings.

One feature I was eager to incorporate was sonograms. For those people who learn things visually, they offer a fascinating insight. Perhaps the best example is for Reed and Sedge Warblers. Many beginners get caught up in listening for the timbre of the notes (the colour, the tone), when the important attribute is pattern. On a sonogram, the 'steady Eddie' nature of Reed Warbler song is immediately apparent in the arrangement of marks on the page, compared to the riffing Sedge Warbler, who finds a little jazzy beat, often repeats it to the point of a stuck record, but then switches to a whole new rhythm.

If sonograms are not something you've delved into deeply before, the book describes how to read them. Raw sonograms from field recordings are often 'dirty' with background noises, so (in a moment of madness) I decided that the answer was to hand-draw idealised versions – all 200 of them!

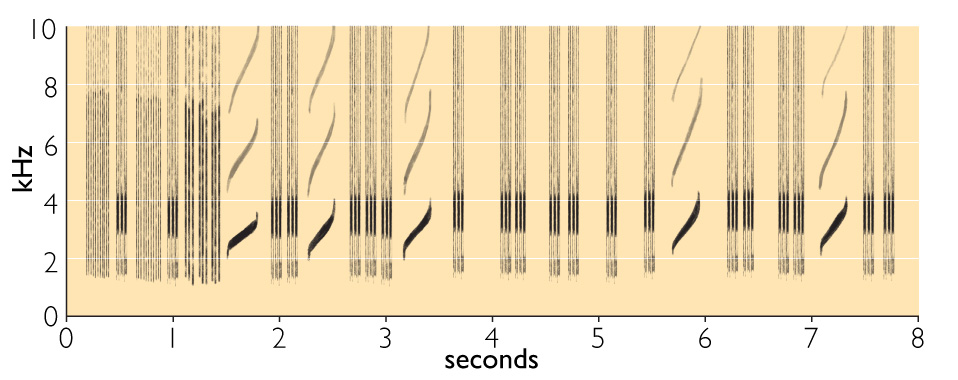

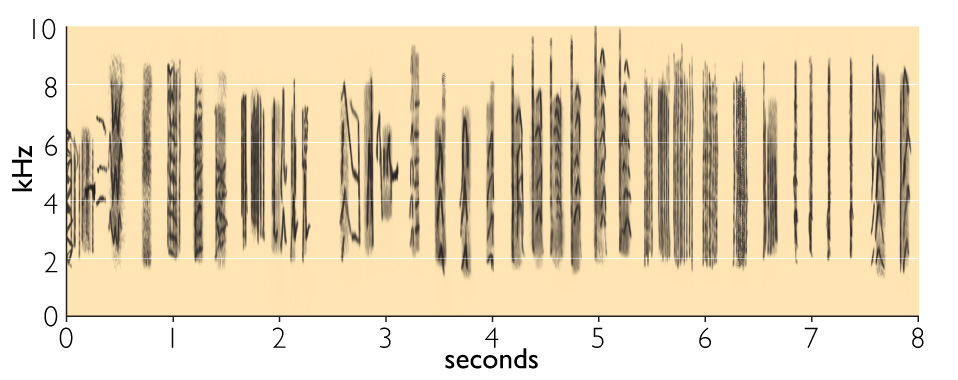

Eight-second sonogram showing clips of Sedge (top) and Reed Warbler songs. With the Sedge Warbler, the next eight seconds might look very different, but you can immediately see the more complex, creative rhythms, with repeating motifs that can then change in an instant, compared to the more steady 'note at a time' of Reed Warbler.

The book also presented the challenge of how to phonetically transcribe sounds (writing down a bird sound in words). If each of us was given that task, we would all come up with a different version, but in the book, I have applied some simple pronunciation rules so that you know what I mean. I also felt it would be useful if the transcriptions convey something of the all-important pitch changes of a sound. For example, the hweet of a Common Chiffchaff rises, so why not make the text do the same?

Section three of the book is a text-only reference guide, with sonograms where helpful, to 250 British bird species.

Whether I've achieved my aims, only time will tell. But for me one of the interesting outcomes of having immersed myself so much in sounds is what I have learned along the way. I realised how I had ignored the calls of some of our most familiar birds. Take a particularly common species, such as Woodpigeon. The I don't want to go, I DON'T want to go, I DON'T want to go song is incredibly familiar, but I realised my ears had been closed to the mer mawwww call, which is where a male indicates a suitable nest site to a female, and also the MO m'm'm'mawww call in his bowing display.

It has also made me seek out sounds I had previously overlooked, and then take the time to soak them in. I couldn't remember listening to croaking Razorbills before (drowned out as they usually are by the belly laughs of Guillemots), nor the ultra-high-pitched 'running a wet finger around a crystal glass' sounds of Black Guillemot. It also finally forced me on a pilgrimage to Skomer to hear Manx Shearwaters: to have 100,000 wheezing 'chickens' hurtling through the darkness around you is truly exhilarating.

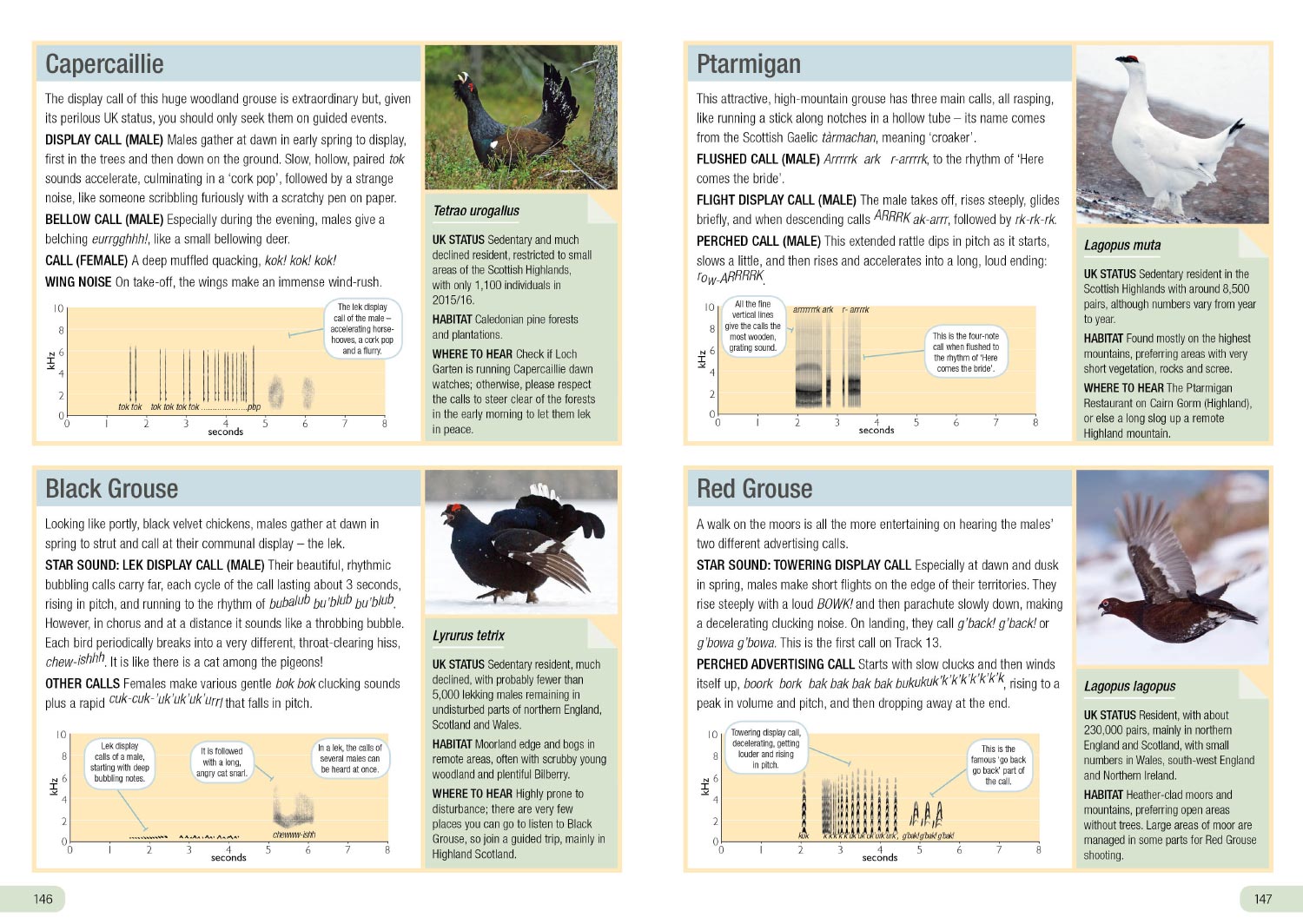

A spread from Section 3; here the calls of grouse, including the 'cat among the pigeons' calls of Black Grouse.

Do I have a favourite bird sound? No – I genuinely find them all fascinating. But there are some that certainly gladden my soul, such as the exuberance of Tree Pipit in song flight, while the song of Common Cuckoo remains a shot of pure happiness.

There is an element of lament here, too. My mum and dad kept notebooks of the birds they saw in the 1960s in their home village in rural Worcestershire. On spring walks they'd see (and hear) European Turtle Dove, Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Eurasian Curlew, Northern Lapwing, Willow Tit, Common Cuckoo, Grasshopper Warbler, Common Redstart and Common Nightingale. My mum still lives there, and when I visit I know that all those voices are now absent from the choir.

This spring, I got to use some of my recordings to help compose a track of pure birdsong for the RSPB. It is an attempt to get nature into the charts in time for International Dawn Chorus Day on 5 May – a wake-up call to a mass audience that nature is in crisis and we can't allow it to fall silent.

You can download the track for about £1 from all the major online record stores, or head to here for quick links. This isn't a money-making charity single, but we are required to put a charge on it for it to be chart eligible, so any proceeds will go to the RSPB reserve network.

More than anything, I hope you have a birdsong-filled spring, and take time to really appreciate it. We are so lucky to have it.

Adrian Thomas is a lifelong birder, who has worked for the RSPB for 19 years, leading projects such as No Airport at Cliffe, #SaveLodgeHill and the creation of Medmerry reserve. He was editor of the Birds of Sussex, which won the BTO Best Bird Atlas award in 2017.

You can buy Adrian Thomas's RSPB Guide to Birdsong at a discounted price via our Bookshop.