Lanceolated Warbler: Shetland, October. A typical view of this species, following extraction from a mist-net! The mantle is heavily streaked, with the black streaking extending to the tips of the feathers, and the rump is also heavily streaked. A key feature is the neat, well defined, fringes to the tertials, which contrast sharply with the dark centres - on Grasshopper Warbler these are broader and less defined, and less contrasting with the centres (photo: Deryk Shaw).

"Lancey": uttering that simple phrase will, for most observers, take their mind wandering straight to Fair Isle. In a British context this magical island is synonymous with the occurrence of this rare Locustella.

This inveterate skulker occurs at its closest in eastern Finland, where singing males are recorded regularly. To the east it breeds discontinuously from the central Urals east across much of Siberia to Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands, Hokkaido and northeast China. The wintering grounds extend from the Indian subcontinent, from Nepal east through northeast India, into southeast Asia and the Philippines.

Evidence suggests that the passage of all populations is via north-east and eastern China, requiring an initial ESE heading for the most westerly populations. The mechanism which brings the species here with such regularity is presumably one of reverse migration and/or post-breeding dispersal: all of those trapped on Shetland have been aged as 1st-winters. Autumn migration is prolonged, departure dates varying considerably in different parts of range: in the west departures from north-east Altai are as early as mid- to late July. Perhaps the peak of sightings in the early part of the autumn relates to birds originating from closer populations, whilst the relatively few late records come from populations further east? A westerly range expansion, as indicated by increased numbers of singing males in eastern Scandinavia, has presumably contributed some way to the recent change in status here from 'mega' to expected rarity.

Lanceolated Warbler: Shetland, October. On the breast there is a gorget of fine streaking, though this is variable. Some have faint streaking, others are better marked. This also extends onto the flanks, though bear in mind that Grasshopper Warblers can also show a streaked throat, breast and flanks, but on Grasshopper this is centred at the junction of the throat and breast (photo: Deryk Shaw).

Formerly an extreme rarity, this popular species has been almost annual since the 1970s, returning its last blank year on the record books as long ago as 1983. In 2005 Lanceolated Warblers topped the 'ton' for accepted British records since 1950. Seven records remain on the British list prior to this date, the first of which was shot by William Eagle Clarke on Fair Isle on 9th September 1908. By the end of 2005 the cumulative British archive contained 108 records. Surprisingly, perhaps, none have yet had their landfall detected in Ireland. Shetland accounts for an overwhelming 86% of British records, with Fair Isle weighing in with a whopping 70% of national records. Away from Shetland there have been just 19 records. Of these, there have been just five Scottish records away from Shetland: three on Orkney (one in 1910 and two in 2003) one in Fife (1987) and one at sea in Sea area Forties in 1978. Northeast England musters just four records: two in Northumberland (1984 and 1985) and two in Yorkshire (1994 and 1996). Lincolnshire boasts records in 1909 and 1996; the well-watched Norfolk coastline contributed records in 1993 and 1994 and Suffolk one in 1997. Considering its rarity elsewhere it is perhaps surprising that Bardsey (Caernarfon) has produced three birds (1990, 1994 and 1997) and the well-watched Isles of Scilly yielded their first as recently as 2002. Perhaps the most impressive record was of one extracted from an inland mist-net at Damerham (Hampshire) on 23rd September 1979.

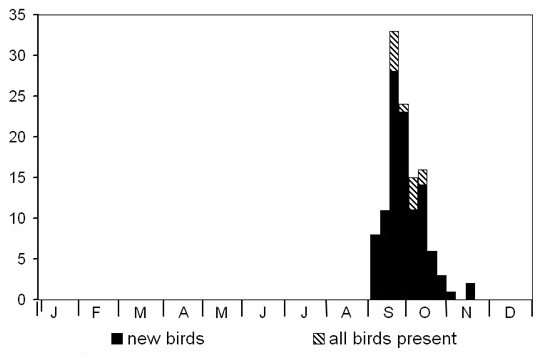

Lanceolated Warbler Monthly Occurrence Graph to the end of 2005: Their arrival here is tightly condensed into the latter part of September, with few after mid-October. Protracted stays are rare, presumably reflecting their elusive nature or an urge to move on quickly. The first spring, or summer, bird is still awaiting its discovery by an alert pair of ears!

Around half of the British records have been located over the two-week period between 17th and 30th September, making this one of the earlier autumn rarities that we can expect. The earliest records both occurred in 2000, when one was on Out Skerries on 1st September and another on Fair Isle on 4th September. Following mid-October there is a sharp decline in records, with just nine in the second half of October. Three November records included one on Fair Isle on 1st in 1960, one at Tynemouth (Northumberland) on 13th November 1984 and the latest, one at North Cotes (Lincolnshire) on 18th November 1909.

The recent increase in records is probably a function of several factors. A recent increase in numbers in Scandinavia, where for example 20 singing males were present in Finland at the turn of the century, has been attributed to some of the increase in recent times, as has the increased emphasis on finding rarities on the Northern Isles. With bird-finding coverage at probably its high point it is perhaps surprising that there have not yet been any proven spring occurrences of the species in Britain - though the possibility of a singing spring bird is surely not far off?

The rarity of this species away from the open Fair Isle landscape presumably has more to do with its skulking behaviour, though the paucity of records from well watched, and ringed, east-coast locations is difficult to explain if, as hypothesised, were are only recording the tip of the iceberg for those that make landfall. Even if low densities of Lanceys were making landfall further south. it might be expected that more might have betrayed their presence over the years. However, presently, to stand a good chance of seeing this species here, one must travel north to Fair Isle, where tales abound of confiding birds scuttling around, and over, the feet of observers taking in every detail. Such anecdotes elicit deep envy from those of us watching well-vegetated coastal patches further south!

Lanceolated Warbler: Shetland, October. On the undertail coverts, the shaft streaks are narrow and clear cut, reaching neither the tip nor base of the feather. The markings are blacker, and more obvious, on Lanceolated being diamond or drop-shaped, appearing more 'isolated' than Grasshopper (photo: Michael McKee).

Lanceolated Warbler: Shetland, October. Briefly recalls Dunnock: when feeding the wings are constantly flicked. Always at their happiest creeping about the vegetation, they scurry mouse-like between areas of cover (photo: Michael McKee).

Lanceolated Warbler: Orkney, September. Note the crisp borders to the dark-centred tertials (photo: Kevin Woodbridge).

Grasshopper Warbler: Cheshire, September. Note the diffuse border to the dark-centred tertials (photo: Steve Oakes).

Grasshopper Warbler: Manchester, July. Typically unmarked underneath; some are streaked but this does not include the lower breast and flanks. Although partially obscured here, note the difference in undertail pattern. The undertail markings are triangular, reaching to the feather base, lacking the 'isolated' markings on Lanceolated (photo: Dave Winnard).

References

Cramp and Simmons. 2004 Birds of the Western Palearctic interactive. Published by BirdGuides, Sheffield.

Alström, P., Colston, P. and Lewington, I. (1991) A Field Guide to the Rare Birds of Britain and Europe. Domino, Jersey.

Svensson, L., Grant, P.J., Mullarney, K., Zetterstrom, D. 1999. Collins Bird Guide. HarperCollins, London.