A new study has revealed the monumental feats of Connecticut Warblers during autumn migration.

The research, published in the journal Ecology, found that four Connecticut Warblers flew non-stop over the Atlantic for two full days, from the eastern seaboard of the US to the Greater Antilles, probably Hispaniola. After resting here for a week, the warblers then flew 800 km over open water to the Gulf of Venezuela before continuing on to winter deep in the Amazon basin.

Twenty-nine Connecticut Warblers were fitted with migration-tracking geolocators at their breeding sites in Manitoba, Canada, in June 2015. The tags, which weighed just 0.45 g, do not transmit data, and must be recovered the following year to retrieve the collected information. In 2016 the team successfully recaptured four individuals, a suspected fifth evading capture.

A Connecticut Warbler is fitted with a geolocator in spring 2015 (Emily McKinnon)

Connecticut Warbler is not commonly captured (or indeed seen) by birders across its entire range, so such a mammoth feat of migration was never likely to have been detected. The species nests in southern-boreal aspen-transition habitats in Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and some parts of the northern Great Lakes states like Wisconsin and Michigan, but is not common even within its breeding range. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, the species declined by 62 per cent between 1966 and 2015.

There have, however, been several hints that the species may be undertaking impressive transoceanic migrations. Frank Chapman, the famous American ornithologist, said in 1907 that Connecticut Warblers were "common in the Atlantic states" in autumn and were "excessively fat, no other warbler approaching them in this respect", this weight gain highly suggestive of an impending long migratory flight. Despite their overall scarcity, Connecticut Warblers are regularly recorded on Bermuda in the autumn, including a record of 75 grounded during Hurricane Emily in September 1987. The paper also cites a flock of at least eight attracted to the lights of a Caribbean cruise ship in 8 October 2002, between St Thomas (British Virgin Islands) and St Martin (Netherlands Antilles) islands.

Emily McKinnon, lead author of the study, commented: "We had a big hunch that something amazing was happening based on the lack of fall records on eBird in, for example, Florida, plus the record of a big fall-out in Bermuda was striking. Why would they be out there if they weren't going over water?

"But it was still really amazing [to see the results], and I was really surprised that they all were so consistent in their timing — two birds were out over the ocean on the same day.

"I was also surprised that they did a second long-distance overwater flight to the Gulf of Venezuela after only a relatively short stopover in the Caribbean. That's what a typical trans-Gulf of Mexico migrant might do in total, but for the Connecticuts it's just a short jump compared to their main, two-day flight!"

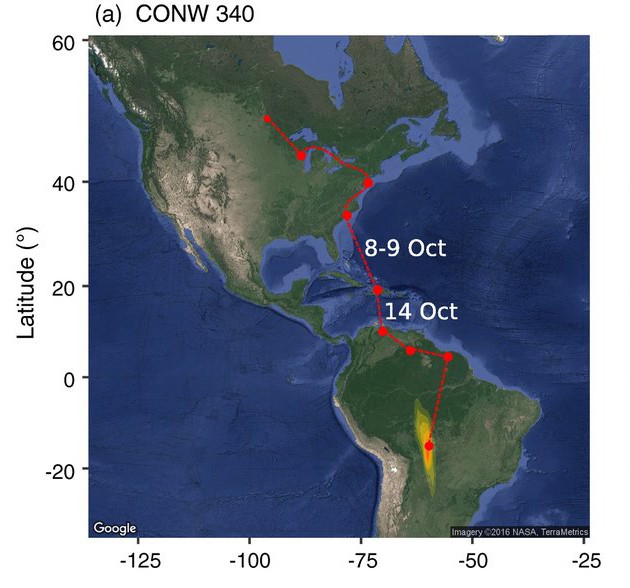

Above: Graph depicting the estimated autumn migration route of one of the four recaptured Connecticut Warblers from Manitoba, Canada. Points indicate at least two consecutive days in the same location (based on longitudes), and estimates for the non-breeding locations are also shown.

The discovery shows great similarities to the 2015 findings that Blackpoll Warblers conduct long transoceanic crossings during autumn migration. Given that this oversea migration route is presumably a strong contributing factor as to why Blackpoll Warbler is an established, near-annual vagrant in western Europe, it seems almost surprising that Connecticut Warbler has not yet been found within the region, even accounting for the latter species' comparative scarcity. Another factor to consider is that Connecticut tends to be much more elusive, generally favouring dense understory and proving considerably more difficult to detect. However, encouraged by this new evidence, rarity hunters will no doubt redouble their efforts and a Western Palearctic record seems a very realistic prospect in the near future.

Reference

McKinnon E A, Artuso C & Love O P. 2017. The mystery of the missing warbler. Ecology. DOI: 10.1002/ecy.1844