So far in this noc-mig series we've covered the basics of equipment, techniques and the identification of some spring migrants. Armed with this information you're now fully prepared to start noc-mig recording. And, judging from social media, many of you are, with garden lists growing with the addition of Water Rails, Eurasian Coots and even Ring Ouzel for a lucky few.

But is building a garden list all that noc-migging is good for? Already this year we have seen how nocturnal observations and recordings can build an unprecedented picture of the overland night migration of Common Scoter. In this article I offer some suggestions for improving the long-term value of your noc-migging.

Submit your records

I am a strong advocate of submitting bird records so that they can be used for education, research and conservation – as a BTO staff member, you would expect me to say that! Nevertheless, many bird reports lack insightful information on common and widespread birds – information that birders can easily provide. Extend that to nocturnal migrants and there is an even bigger gap in knowledge.

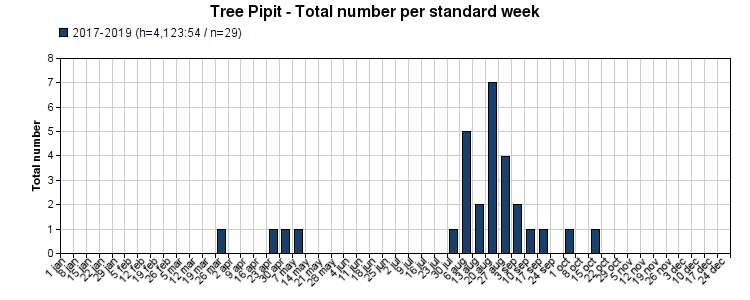

For example, in Cambridgeshire where I record, Tree Pipit is bordering on being a county rarity with an average of just six sightings per year. In the last three years I have recorded 29 (Figure 1). There are probably similar cases across the country where noc-mig data can significantly improve knowledge of species for a county. The potential is even greater when those records are collated across counties and countries.

Figure 1: seasonal pattern of detections of Tree Pipits recorded over Chesterton, Cambridge, from Trektellen (more here).

There are three main ways of submitting your records, depending partly on how regularly and consistently you make nocturnal recordings. One is to send the records directly to your County Recorder (full list here), but I think a better option is to use one of the online portals, which will mean the data is available for a wider range of uses. In the UK, BirdTrack is an obvious place to enter data – it can feed into research and monitoring and is automatically and freely available to the relevant county bird recorder (some 70% of recorders currently receive records from BirdTrack). BirdTrack is a good option if you want to submit highlights or notable nocturnal species, or if you do not intend on making noc-mig recordings regularly.

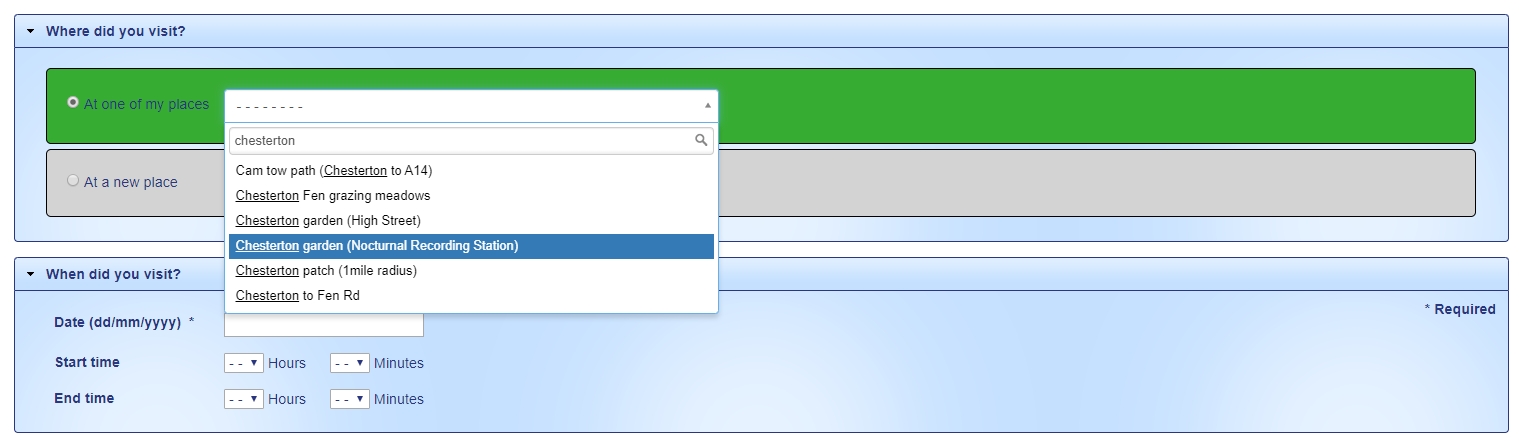

Figure 2: unless you don't mind noc-mig records getting mixed in with your regular garden records on BirdTrack, it might be best to create a separate 'place'. Also, add 'noc-mig' or 'NFC' in the observation comments so future data users know how they were collected (BirdTrack)

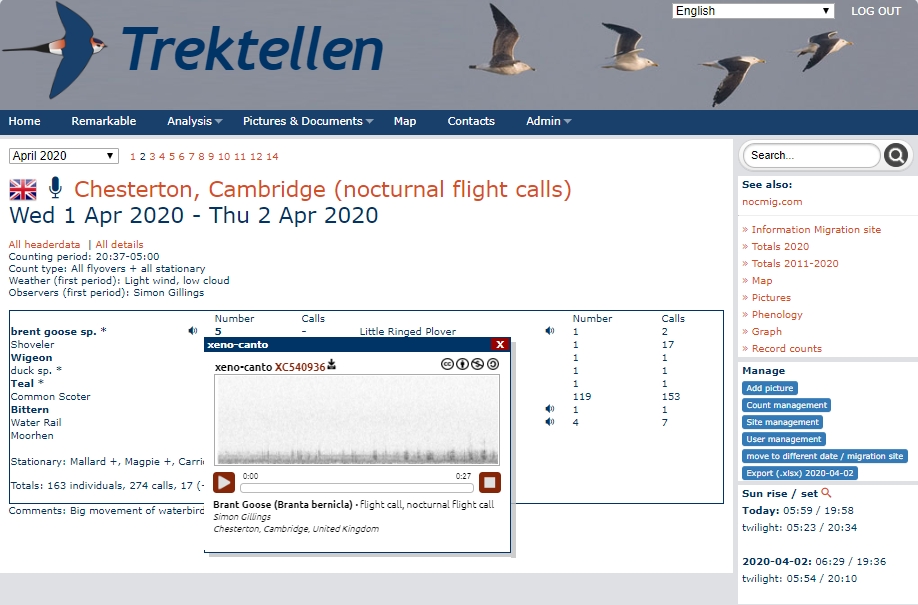

If you're planning to record regularly and really want to maximise the value of noc-mig recordings, consider submitting the data to Trektellen. Originally a Dutch creation for visible migration counts, Trektellen is now the hub for European noc-mig data, with more than 160 sites registered and some 115,000 hours of recordings to date. Trektellen has been specially designed to facilitate noc-mig data entry, with fields for numbers of individuals, numbers of calls and options to link to recordings in Xeno-Canto.

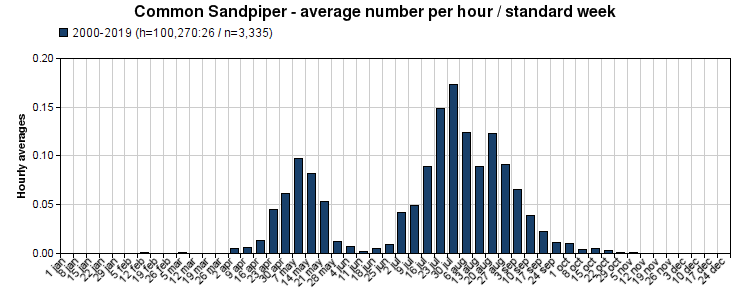

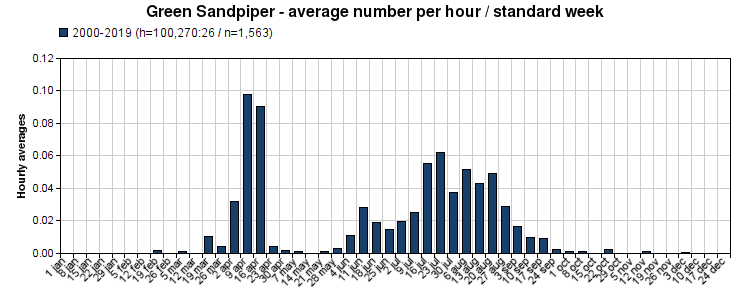

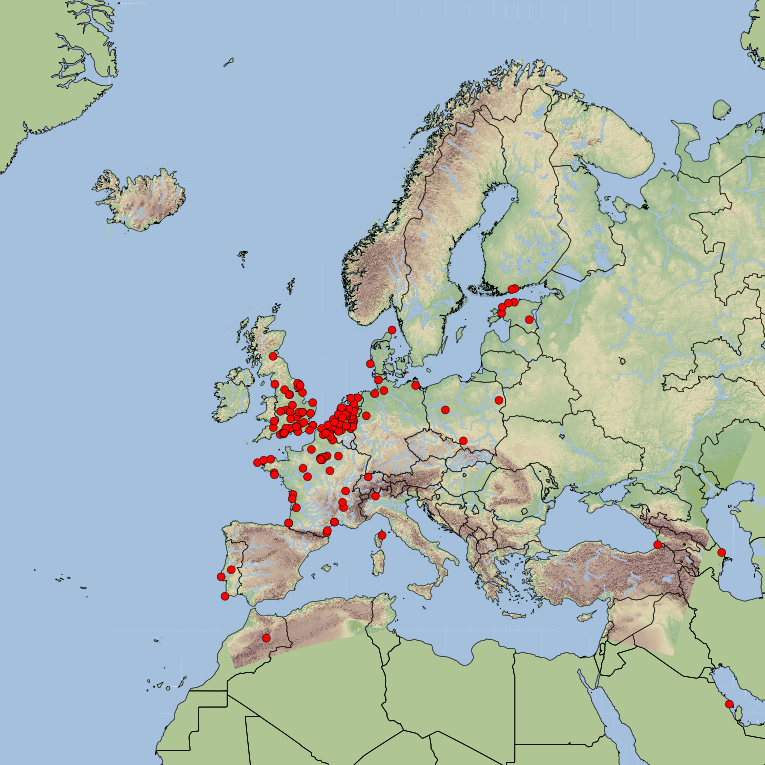

Once uploaded, totals are publicly visible and can be shared via social media. As well as this, there are some great summary maps and graphs which are invaluable for getting to know what is flying when and where (Figure 3). Trektellen data for the UK is added to BirdTrack every single night, so the records are automatically available to county recorders.

Figure 3: seasonal pattern of reporting of nocturnal migrant Common Sandpiper (top) and Green Sandpiper (middle) recorded at sites across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East (bottom). Note that, because all species have been counted and total recording effort was logged, we can express number of birds per hour and directly compare the species.

A little bit of standardistion goes a long way

Submitting all species (not just highlights) and entering start and end times significantly increases the value of data. It means, for example, that we can calculate the number of birds detected per hour (Figure 3) and safely infer when particular species were not detected (versus just not reported). As David et al say in their scoter article, these are often difficult things to assess from more casually collected observations and consequently affect what conclusions can be drawn from them. BTO, SOVON, The Sound Approach and Trektellen teamed up to write some simple guidelines to follow when collating and submitting noc-mig data via Trektellen. The full protocol can be read here, but the key points are as follows:

- If possible, record at least once a week in key migration times;

- Record start and end times and ideally submit counts in hour blocks.Do not include in totals any birds counted before civil dusk or after civil dawn. We use the civil dusk rather than sunset to avoid roost movements. Likewise we use civil dawn rather than sunrise because many diurnal migrants (e.g. finches and wagtails) start their migration just before true dawn, so including them in noc-mig totals is unhelpful;

- Count all birds flying over. Even if you think a Common Moorhen is a local bird flying around, log it. For some species we can't conclusively separate migrants from local night-active individuals; in any case, the latter are of interest in their own right.

- Be cautious! Identifying nocturnal bird calls can be difficult. If in doubt log as uncertain, or as 'species unidentified' and link to your recording uploaded on Xeno-Canto.

- As far as possible, provide estimates of the number of calling birds. Sometimes this is difficult, especially for flocks of ducks and for species like Redwing, which may call multiple times. All counts can be qualified as 'estimate' or 'minimum'.

Sharing recordings

Just as the data from noc-mig are an invaluable resource, so too are the actual audio files.They provide examples to help other people to learn bird flight calls and may be useful in future studies of vocalisations. The Xeno-Canto website is a great place to upload calls of known identity. It also allows the upload of mystery calls (see here). So, if you have something you can't identify, try uploading as a mystery and seek the help of the Xeno-Canto community. As Xeno-Canto recordings can be tagged within Trektellen, you can post your data and link to the recordings so people can hear and help to verify unusual or unidentified calls (Figure 4).

Figure 4: sounds uploaded to Xeno-Canto can be tagged in Trektellen, meaning they can be played directly from the Trektellen summary page. See also the 'Remarkable' page, where highlights from across Europe are listed, many with linked sound files (Trektellen).

County records and rarities

The growth in noc-mig recording may be both a blessing and a curse for some counties and their recorders, who are already dealing with growing volumes of data from multiple sources, forever shifting taxonomies and changing patterns of birder behaviour. Noc-mig will provide new insights into hitherto under-recorded species, but it will, sooner or later, generate records of locally scarce and perhaps even nationally rare species that will need verification. This will be an evolving area so I will conclude with a few thoughts for the noc-mig beginners and experts and for the county recorder community.

Other specialised activities, like intensive ringing and dedicated gull-roost watching, have generated records of species with little or no previous history of occurrence and noc-mig is already proving to be no different. I think that places an onus on county recorders to be open-minded, but that doesn't obviate noc-miggers from being cautious and backing up claims with good documentation and analysis.

Figure 5: nocturnal flight call of a Baillon's Crake, recorded in France during the invasion in 2019. How many rarities like this are waiting to be discovered, flying over sleeping birders' backyards? (Stanislas Wroza).

While the identification criteria for many species are well understood, often established in places where the species in question are common, there are still some species that remain challenging. Certain species that might not require a description because they are visually distinctive may be challenging to identify based on flight calls. A good example is Pied Flycatcher and one could argue that claims might require a description. It is probably fair to say that exactly what constitutes a well documented audio-only submission has yet to be resolved. Magnus Robb's in-depth analysis of the recent Paddyfield Pipit in Cornwall offers a lot of pointers.

Incorporating sound recording expertise into rarities committees will help in the assessment of noc-mig records. Even with the best documentation, some records may remain in a pending state while patterns of nocturnal occurrence are accumulated. Submitting data and sound recordings will help to amass the knowledge needed to properly assess records. Beyond garden lists and even county lists, I hope that in time the records that we can all provide will help to elevate our understanding of migratory birds at local, national and international scales.