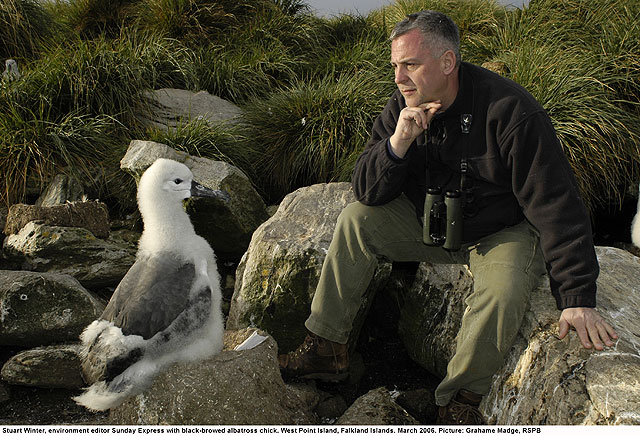

Author with Black-browed Albatross (photo: Grahame Madge, RSPB).

She was sitting blinking in the face of a South Atlantic gale — a giant, cuddly toy of a creature, nature's own answer to a Womble. All fluff and flab, her cuteness accentuated by the blackest of beady eyes, she had been designed to survive some of the harshest conditions on our planet. High in her remote cliff-top sanctuary, the bundle of soft, white down waited patiently, insulated against wind and rain, sleet and salt spray. Soon, she would be undergoing one of the natural world's great transformations from adorable chick to the sleekest of flying machines — a powerful, Black-browed Albatross.

Once her floppy wings had developed their powerful flight feathers, the albatross would begin her seven-year odyssey riding the waves. Only when she had matured into a beautiful porcelain-white adult would she return to the same craggy sanctuary on the remotest outcrops of the Falkland Islands to raise her own chick.

As I gazed deeply into her black, limpid eyes though, I knew it would be a journey she was unlikely to survive. For millions of years albatrosses have graced the high seas with their magnificent flights of fancy, careening over tempestuous waves on wings up to 12 feet in length.

Mariners throughout the ages were spellbound by the albatross's mastery of the seas. To kill one, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge told in his epic poem the Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, was a portent of catastrophe.

Today, albatross numbers are declining catastrophically because of uncaring and avaricious sections of the fishing industry. Every five minutes an albatross is doomed to a dreadful death by the recklessness of the fishing fleets sucking the seas dry. Once a young bird fledges it will roam the southern seas searching out prey (squid, fish and crustaceans) among the towering waves.

However, the lure of succulent squid for the restaurant tables of the Spanish Costas or Patagonian tooth-fish to delight expensive American palates has seen these bountiful waters patrolled by highly sophisticated fishing vessels from Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina equipped with trawls and lines that are lethal to any passing seabird.

A three-inch hook baited with a piece of rotting fish is also attractive for an unsuspecting albatross and yet millions of these floating death sentences are being cast into the seas by fishing boats whose "long lines" can stretch out 80 miles across the ocean. What seems easy food for the bird all too quickly becomes a last meal. Before the hook sinks, it floats menacingly on the swell for a few moments, enough time for a passing bird to grab the bait and find itself cruelly trapped by the sharp barbs tearing into its throat. As the hook submerges, the bird drowns — slowly.

Black browed Albatross (photo: Grahame Madge, RSPB).

It is a story played out 100,000 times every year and has left the majority of the world's albatrosses, 19 of the 21 different species, near extinction. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and its partner BirdLife International are the leading players in the global Save the Albatross Campaign, a movement that has captured the imagination of Prince Charles, Sir David Attenborough and environmentalists around the world.

The RSPB invited me to visit one of the most important albatross colonies on the planet to witness the essential survey work being carried out in the Falklands. The journey was an epic worthy of an albatross. A 20-hour flight by RAF 747 from Brize Norton, followed by a lengthy crossing by light aircraft over the bleak Falklands hinterland, the Camp, took us to one of the westernmost islands of the South Atlantic archipelago. Our journey was still not finished. A four-hour sailing by fishing boat, across thankfully calm seas, and a long "yomp" through towering tussock grass led us to the heart of West Point Island's garrulous seabird city on a cliff ominously known as the Devil's Nose.

Here, the albatrosses share the precipitous slopes with comical Rockhopper Penguins and noisy "Johnny Rooks", the scavenging Striated Caracara, one of the world's rarest birds of prey. All our attention was focused on the albatrosses though. Once you've gazed into the knowing, deep, jet eyes of an albatross chick as it sits on its muddy mound of a nest, you know this is a creature worth preserving. All too tragically, the results from this winter's monitoring programme reveal that the future is indeed black for the Black-browed Albatross.

The Falklands hold around 70 per cent of the world's Black-browed Albatrosses but since 1999, 70,000 have perished. This season's census shows that over the past four years there has been a decline of 18,584 birds. This rapid rate of reduction is unsustainable for a bird that can live more than 40 years but has an incredibly slow reproductive rate. Today it is officially declared as endangered. What is so galling is that protecting these wonderful birds would cost a fishing boat skipper a few pounds.

Falklands Conservation, which carried out this year's survey, and the islands' own small fishing fleet have worked together to make sure their boats are aware of the albatrosses' plight. By fishing at night, fitting boats with bird-scaring devices, weighting lines and using thawed bait which sinks more quickly, the instances of albatross deaths have fallen.

But the albatrosses roam far from the safety of the Falklands territorial waters and in the vast South Atlantic they can fall prey to other fleets, often pirate fishing boats. Here, trawlers can leave albatrosses with smashed and damaged wings as their nets have heavy cables. Birds, drawn to the boats by the fish guts and offal being discarded over the side, stand no chance as the heavy metal flexes crash down on their frail bodies.

More sickening are the reports of albatrosses being deliberately caught by ravenous sailors on unregistered boats from the Far East. Conditions aboard are so appalling for the crews, paid a pittance and handed only survival rations of rice, that an albatross can provide welcome protein after a year at sea. Researchers have recently been finding filleted albatross carcasses thrown to the seas after providing meals for hungry deckhands. What a tragic end for a creature designed by nature to rouse and thrill.

There is certainly nothing more inspiring than to watch an albatross's nest among the boulders and slopes of one of the most remote places on earth. My guide for this moment of communion with nature was Grant Munro, the director of Falklands Conservation, whose scientists have been plotting the birds' disastrous fortunes. Scottish-born Grant, a forester by profession, laments their plight with a look of despair. As we listened to a mother bird feeding her noisy youngster, he told me of his fears for the chick's future.

"They are remarkably tame birds, and if you sit quietly you can watch them as they await their parents' return. The chicks remain on the nest so they do not get lost before the adults return with food, often after spending up to several days at sea. Here, in the colonies, the birds are doing well. They have a successful breeding rate. The problems are at sea. We conduct a count every five years around the islands and that shows that the population is around 400,000 pairs but declining at the rate of around 15 per cent every decade. This relates to a breeding pair being lost every hour which is very worrying. They are a long-lived species and do not have a high reproductive rate, so even a two per cent decline in the adult population can lead to a decline which is difficult to recover from."

"The cause is mortality at sea. The large industrial fishing fleets have caused a high death rate. The main factors have been the expansion of the fishing industry in the southern oceans in recent years, both long lining and trawling. Unfortunately the birds are being killed by the operations of these vessels." Pointing to the fluffy chicks, he says: "These little fellows are about four months old and will take their first flights during the early weeks of April. They will then spend the next seven years at sea and during this time there are lots of threats when they come into contact with the fishing fleets."

The RSPB's Grahame Madge has studied the declining fortunes of the planet's albatrosses. All but two of the world's 21 species are suffering and the mighty Wandering Albatross — with the largest wingspan of any bird at 13ft — is just one teetering on the brink. For the UK, there is an onus to preserve these wonderful birds: seven of the threatened albatrosses nest on British overseas territories.

The RSPB recently set up the Albatross Task Force to work with fishermen and show how easy it is to use techniques which will reduce deaths. The birds' future rests with such initiatives. "It is the fishing fleets around the world which are killing these creatures," said Madge. "We have to work with the fleets to try to bring in measures to stop this appalling slaughter. "The more time delayed and wasted in bringing in these measures, the more birds we will lose. For 50 million years albatrosses have flown the oceans but since their brief contact with man they are in danger of disappearing altogether."

Ironically, preventing an albatross death can be so simple. Putting streamers out behind the boats to discourage the birds from coming in too close and seizing the baits has already proved successful. Equally, setting the lines at night and using bait that sinks quickly also helps. Where such measures have been used, albatross mortality has come from thousands down to almost zero. What's more, they are very cheap. The difficulty is convincing the fishing industry. The plight of the albatross is also touching the hearts of the good and the great.

Prince Charles has become the champion of the albatrosses' cause and has made some of his most passionate speeches in their defence. Results from the latest survey in the Falklands are being sent to Clarence House. He recently said of albatrosses: "They are now dependent upon our whim, yes, our whim...I have always felt that if their wanderings should cease through man's insensitive hand and that magical moment of a swallow's first arrival, or an albatross's return, disrupted for ever, then it would be as if one's heart had been torn out. If this was to happen, and we are rapidly approaching the very real possibility with all 21 species of albatross, then we would sacrifice any claim whatsoever to call ourselves civilized beings."

If you want to help the albatross, look at the Save the Albatross website at www.savethealbatross.net.