Note-taking or not taking — that is the question.

With the advent of the compact digital camera that anyone can stick in their pocket, has the art of note-taking really drawn its last breath? Will it be missed? As a (not-so-recent) graduate of the bird observatory and bird recording school, I'd wholeheartedly say that without your notebook you're missing out. But why carry a notebook? What can't I do on my iPhone or from memory, or with a click of the shutter of a digital SLR? There are a whole list of reasons why anyone serious about their birding should carry (and use) a notebook, so hopefully here I can highlight just some.

Descriptions

It's mid-May and you're cutting a lonesome figure, trudging along the coast. Those endless daydreams come to fruition when the fence ahead of you is home to a fine male Woodchat Shrike. Chestnut crown — check. Black mask — check. Black wings, white panel — check. Black tail — check. Can't mistake it really. Well done!

Woodchat Shrike, Winterton Dunes NNR, Norfolk (Photo: Mark Bicknell)

So, chuffed with yourself, you're off home to spread the word and enjoy the find. Sadly the bird doesn't stick, but you've seen it and that's all that counts. With the description written and submitted, you then find the county recorder on the phone after news comes out of a Balearic Woodchat Shrike in the neighbouring county the very day after your bird. "Your bird did show white on the scapulars AND primary bases didn't it?" is the obvious question asked. Errr...a county first gone begging?

Balearic Woodchat Shrike, Duncormick, Wexford (Photo: Sean Cronin)

But you've probably got a good digital camera anyway, so why not just photograph the beast? After all, a picture is worth a thousand words, right?

So the next winter you're down at your local reservoir when up pops a dead ringer for a Redhead right in front of you. It's constantly up and down and barely lets you get your bins on it, never mind a 'scope or digiscope set-up. The obligatory water-skier passes by and the bird disappears, never to be seen again. So how extensive was the black on the nail (bill tip)? Did it really show a white subterminal band? You never managed a photo of it, but if you'd managed to sketch it with those fleeting views then this permanent reminder may be vital in proving an identification.OK, so these are both rather extreme examples, but there really is no substitute for taking good notes in the field whilst actually looking at a bird. A picture might tell a thousand words, but it still doesn't capture everything. For some species, key identification features may be quite esoteric, and freeze-framing a bird for a moment in time doesn't convey these. When we talk behaviour, we don't mean fights on the steps of a hide for a glimpse of an American Bittern, but more the most fascinating, or note-worthy (!), aspects of a bird. These will certainly help in the identification of some tricky species. Does your bird pump its tail, does it hover, does it glide or make shallow or steep banks?

Take a more real example, one that I've regretted ever since. It was May 1990 and we'd travelled most of the length of the country (Norwich to Sumburgh) in pursuit of the last twitchable Pallas's Sandgrouse. It wasn't playing ball, and in pretty poor weather we finally caught up with the bird at Loch of Hillwell — what relief!

It was only later when we saw photos of the bird that something didn't quite seem right. The photos showed a rather obvious adult male, but for all the world I was convinced we'd seen a female. OK, so we've all used and abused the two-bird theory before, but this did seem odd. Looking back on my rather scant notes the only thing of use was "Blue-grey forehead, orange hue on back of crown and throat. Sandy brown/grey on neck (may be ruffling). V prominent barred black-sand on scapulars. Faint, narrow crescents on under-tail coverts." Now this isn't exactly the best description of a female, but it certainly doesn't fit the nice adult male in the photos. Add to this that, despite its being present at Hillwell and Quendale from 19th May to 4th June, we'd seen it on the only day that it was seen elsewhere, at Loch of Spiggie. Assuming we saw the same bird, of course. Would better notes have helped us find a second bird? Who knows...

Pallas's Sandgrouse, Quendale, Shetland, June 1990 (photo: www.robinchittenden.co.uk).

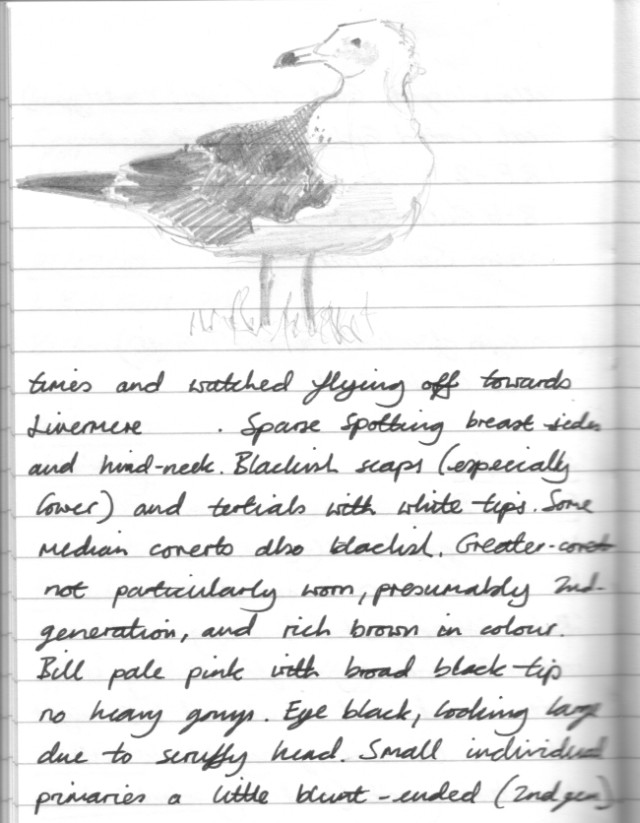

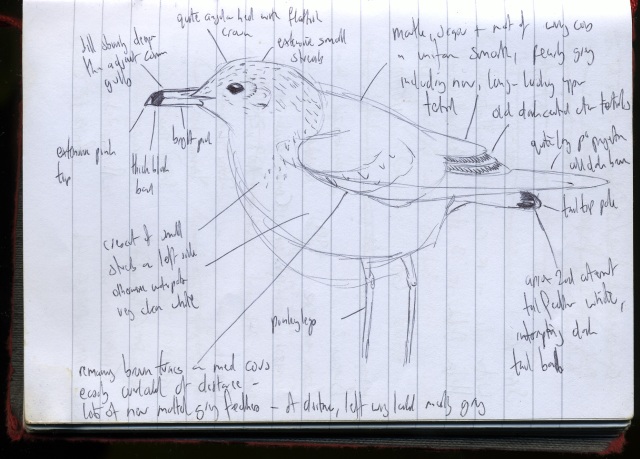

With many difficult species, or species groups, some of the key features may be ones that require a detailed written description. This bird, showing some characteristics of fuscus Lesser Black-backed Gull, may be hard to prove, but a solid field description will help its cause.

Bird showing characteristics of fuscus Lesser Black-backed Gull (courtesy of Pete Wilson).

Remember as well that habit-forming is the best way to become good at what you do. Practise writing descriptions on common species, and you'll not only become more familiar with them (key to identifying rarer close relatives), but be well versed in the art of note-taking when the time comes.

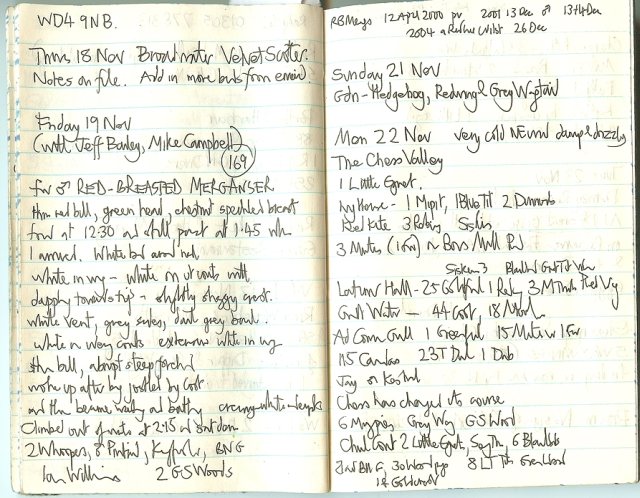

Note Lee's extensive notes, including notes on familiar species (courtesy of Lee GR Evans).

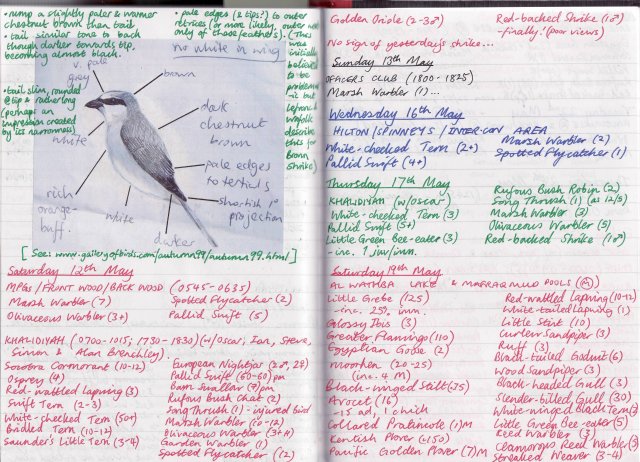

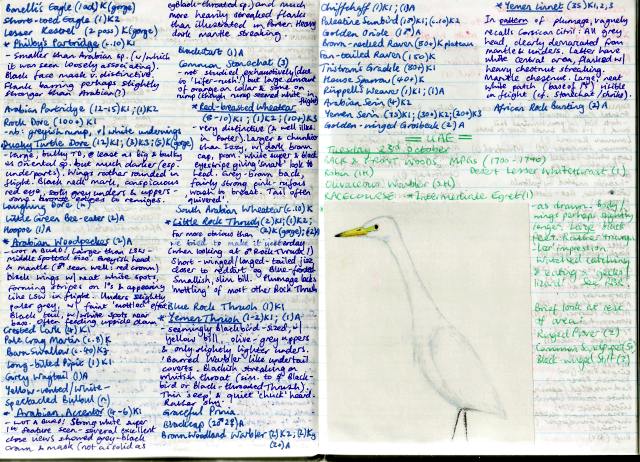

Sketching

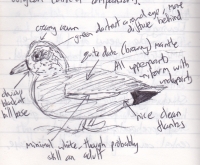

This almost neatly brings us on to the art (sic) of field sketching. Whilst we certainly aren't all gifted with the enviable ability to produce beautiful field sketches, your own efforts are a personal reminder of a day out and give you a chance to really look at birds. Have you ever really looked at the difference between old outer and new inner greater coverts on a migrant Meadow Pipit (or Richard's Pipit)? Sketching really makes you look at all aspects of a bird and take in far more than you would by just pressing a shutter or 'ticking and running'.

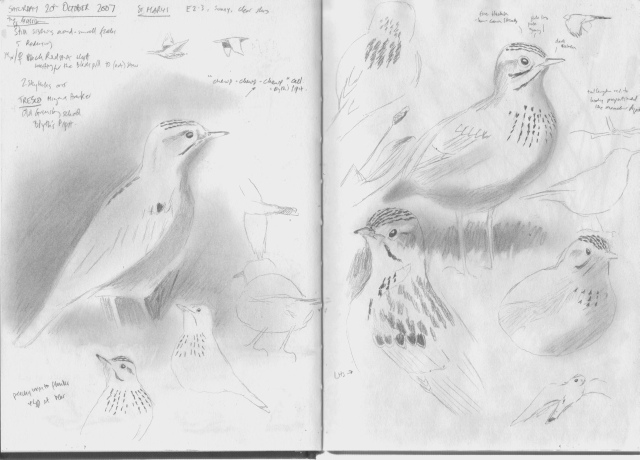

Take this simple sketched sequence of a Blyth's Pipit on the Isles of Scilly and how so many of the salient features can be picked up, with the end product an accurate representation of the bird.

Blyth's Pipit (courtesy of Richard Thewlis).

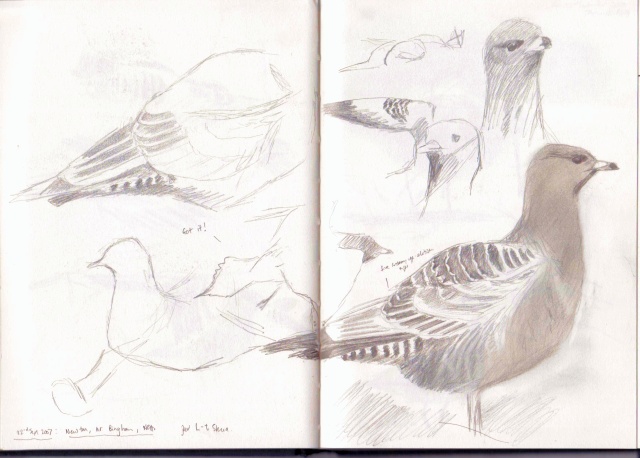

My effort is rather overshadowed, though, by this more impressive rendering of a Ring-billed Gull:

Ring-billed Gull (courtesy of Kev Wilson).

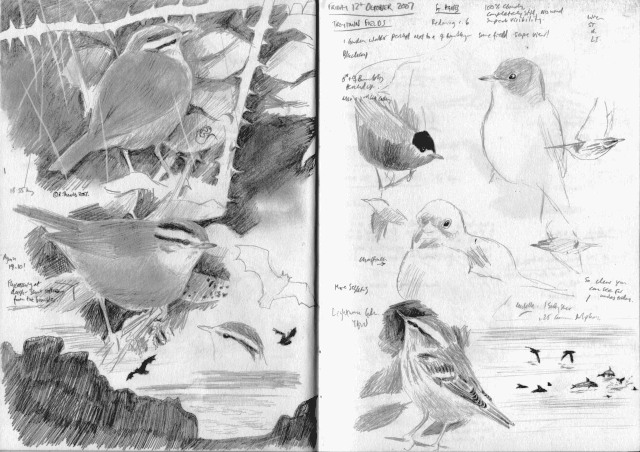

Even more impressive are the following, and I'm using this as a gratuitous excuse to show off some excellent field drawings from the notebook of Richard Thewlis. Richard sums up his attitude nicely thus:

"For me, whilst it can be satisfying getting a good photo, I always find it more rewarding to study the bird, to really look at it in the field, rather than always just be trying to line it up in the viewfinder, and only studying the subject on a computer screen when you get home. Often you end up realising there are things that you failed to observe whilst the bird was in front of you.

Everyone prefers different media — some weatherproof books, others spiral-bound pads or A6 Black 'n' Red ruled notebooks. I've used Seawhite of Brighton A5 hardback books for many years — they are nice to draw on, but the paper buckles when you paint on it, so I often carry a watercolour pad as well."

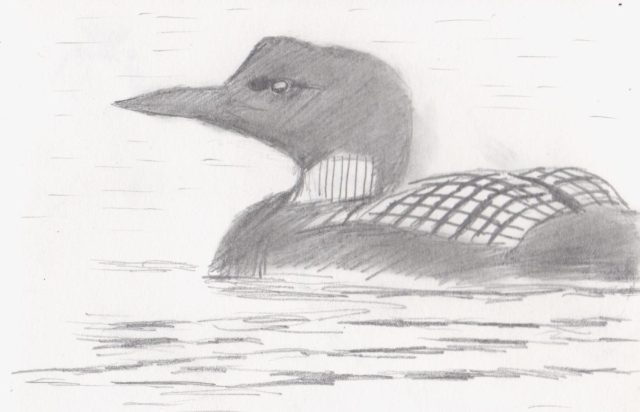

Great Northern Diver (drawings courtesy of Richard Thewlis).

Surveys

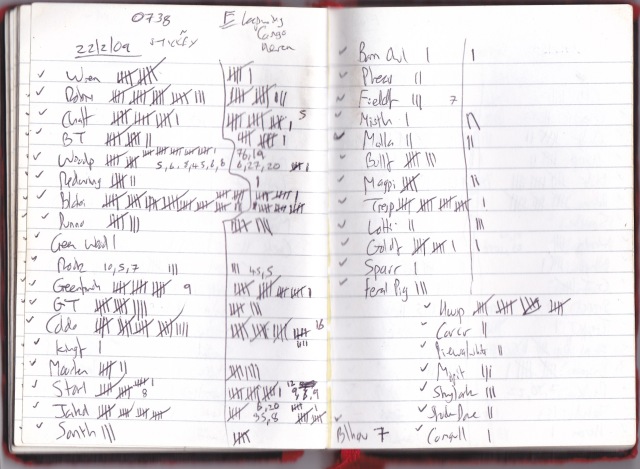

Certainly the greatest use, for me, of my field notebook is counting and recording. I'm probably one of those birders who grew up doing this, so can never resist filling my notebook with five-bar gates. You'll notice that many of my species names are rather made up, and I've never quite got into the habit of using BTO two-letter codes, preferring my own unique system. As long as I can interpret my notes, that's fine. My notebook serves far more than just that, though, and generally fills up with notes, ring numbers and a whole array of perhaps useful information.

One Bird Atlas TTV (Timed Tetrad Visit) (courtesy of Mark Grantham).

Similarly, a page from the notebook of Kev Wilson, the warden at Gibraltar Point Bird Observatory, shows a similarly hectic visible migration count one morning.

One morning's 'vis-mig' counting on the east coast (courtesy of Kev Wilson).

Writing up

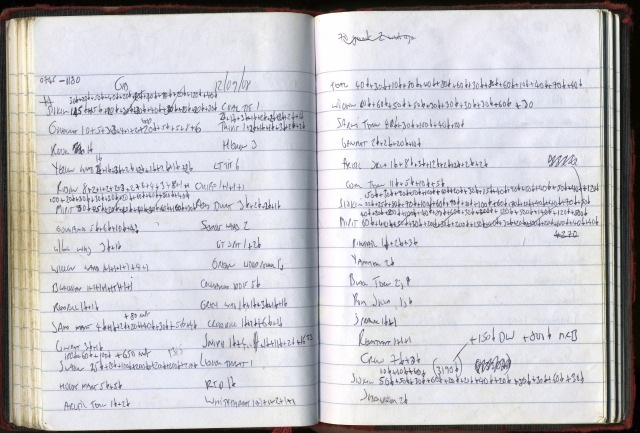

At the end of the day, these are your own records, and should be kept by you for reference and reflection. Many choose to write up their day's notes into a neater and more coherent log, but I simply input them onto the web (BTO survey pages, BirdTrack, colour-ring submissions, etc.). A few examples here show the transcribed notes from Nick Moran's time in the UAE, before he returned to the UK to organise the BirdTrack online survey.

The UAE's second record of Brown Shrike (courtesy of Nick Moran).

Yemen and UAE birding (courtesy of Nick Moran).

So, no matter how you might use your notebook out in the field, make sure it's always right there in your pocket. Get used to using it and filling it with memories, reminders and that mass of information that'll only be lost if left in your head.