For the past two years, the Cameron Bespolka Trust has awarded a scholarship for one young British ornithologist to attend a young birders' event at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York. For the first time in 2016, Amy Hall jetted off on this once-in-a-lifetime trip followed by Max Hellicar in 2017. And, on 10 April while out on a morning stroll, news came through that'd been awarded this year's scholarship. Eureka!

The event, which is held from 12-15 July, was created by the staff at the lab with the aim of bringing teenagers with a deep-rooted passion for birds together from across the planet and to inspire and help those to pursue a career in ornithology. To help make this happen, Cornell's top people would be on hand: Chris Wood (Assistant Director of Information Science), Jess Barry (Program Manager for the Macaulay Library) and Ian Davis (eBird Project Coordinator) to name but a few. It was an utter privilege to be at this year's camp and words just don't do justice for how incredible the days here were; but anyway, on with the show …

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (Elliot Montieth).

12 July

Following an early arrive into Ithaca, I was met at the hotel airport by Chris Wood, who took me out for a tour of the town before heading off for a morning's birding round Cayuga Lake, where we netted 69 species in a few hours.

Many of these were at Montezuma wetlands, an area of state-owned land which spans over 9,800 acres. While here we encountered Purple Martin, Tree Swallow and Northern Rough-winged Swallow darting over our heads; Willow Flycatcher, American Yellow Warbler, Warbling Vireo and Northern Flicker dotted about in the woodland; Least Bittern, Great Blue Heron and American Bittern over the marshes and Sandhill Crane, Greater Yellowlegs, Least Sandpiper, Trumpeter Swan and Blue-winged Teal all on the pools. Raptors were also prominent with no fewer than five Bald Eagles roaming around, Cooper's and Red-tailed Hawks, Northern Harrier and an incredible 41 Western Ospreys!

Purple Martins (Elliot Montieth).

Shortly before heading for lunch and then off back to the Lab to meet the others, Chris took me up the road to see something rather special: Upland Sandpiper! Bartram's Sandpiper, Upland Plover, Papabotte … whatever you want to call it, this is one pretty mad-looking wader. In fact fewer than 20 breed in New York state and as is the story with virtually all Scolopacidae, they're in decline. While on route Chris informed me that there'd been no sighting of this regular pair, the most reliable pair in the state, for several weeks. So, when we arrived and I picked up three juveniles, I was fairly chuffed as I'd proven that they must have bred at this site, which was great news.

Back at the Lab, Chris introduced me to the other young birders I'd be with for the event: Baxter Beamer, Miles Buddy and Aaron Evans to name a few of the folk who'd come from across the world to take part in the event. I wasn't expecting such a diverse array of 'next generation' ornithologists from every background imaginable – it was fantastic.

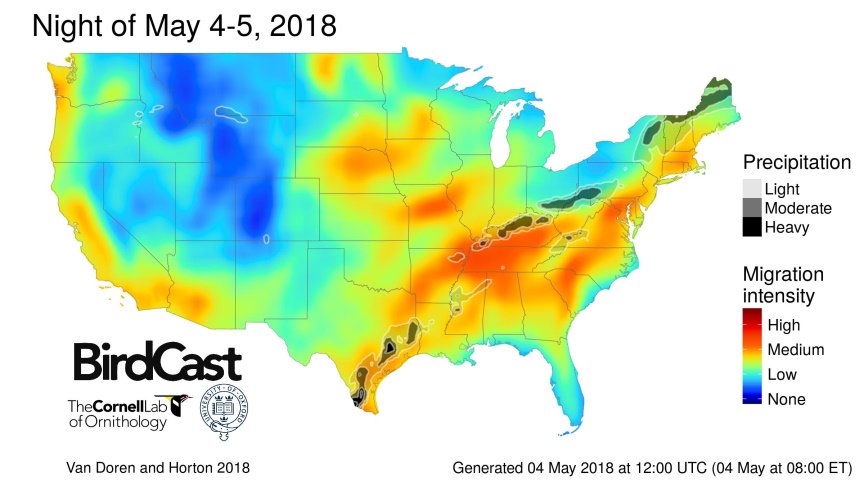

After our introductions at the Lab we headed straight into our first talk by Kyle Horton, a Rose post-doctoral fellow of the Lab who's been studying bird migration across the North American continent via radars. Thanks to Kyle, I can now forecast where bird falls will occur in relation to weather patterns. In addition to this, the Lab is able to see where birds congregate on migration in relation to cities and the affects that artificial lighting have on avian migration. The sheer scale of this project is just the tip of the iceberg of what Cornell is doing.

Migration across the United States overnight on 4-5 May 2018.

13 July

Two options were offered to us at the crack of dawn: either join Chris and Ian for some birding or Jessy and some of the sound guys to do some sound recording. Given how priced out I was back home to even consider sound recording, an area I've always wanted to get into, I took the latter option.

For the next several hours we roamed the Sapsucker Woods documenting just about as many birds in the dawn chorus as we could. The morning duets and melodies certainly rivalled that of any I'd previously encountered back in Europe: Blackburnian Warbler, Grey Catbird, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Red-eyed Vireo, Eastern Wood Pewee, Common Yellowthroat, Chestnut-sided Warbler and so on. The number of warblers in just a small area was quite simply astounding. You can spend as much time as you want with your head stuck in literature, reading the same material in different formats over and over again, but nothing is more educational than actually being there in the flesh, seeing these birds first hand.

Chestnut-sided Warbler (Elliot Montieth).

The two groups swapped and I joined Chris and Ian for a few hours' birding at a local state-owned woodland. I was surprised at how commonly playback is used in the States, in contrast to the negative associations that it gets back here in Britain (and across the Western Palearctic). It's routine to play the tapes of something like Eastern Screech Owl and within seconds have virtually all the local species crowded around the speaker. While I will prefer to remain 'playback-free' back home, it was nonetheless interesting to see the difference in attitude in the States to this often-controversial tactic. The tape brought in new birds such as Chipping Sparrow, Ovenbird, Prairie Warbler and Black-billed Cuckoo to name but a few. I was already close to 100 lifers, just 24 hours into the trip!

A total of three hours was spent on the reserve, trekking through the woodland with both Chris and Ina being excellent guides and very informative about the birds of the area, as well as the calls each one makes. We all learnt valuable lessons such as the flight calls of Dark-eyed Junco, Bobolink and Song Sparrow and amassed a grand total of 58 species. We then tried a few sites for a must-see bird – Mourning Warbler. From what I could gather it was just a Cetti's Warbler in drag …

Blue-headed Vireo (Elliot Montieth).

That evening, John Fitzpatrick (Associate Director), Tom Schulenberg (Avian Taxonomy Specialist) and Daniel Fink (Research Associate) all gave utterly outstanding talks. Dan and Tom's talk did certainly open up my eyes. I must point out that if anyone wishes to apply for the Scholarship, don't apply if you want to come over and see a load of new American species, otherwise you're just wasting the trip. Only apply if you want to be inspired and educated, captivated by the work that the Lab does, so it can help you to understand and pursue the career path you wish your life to follow. If you've got a question, ask it and they'll answer it to the best of their ability; everyone there will bend over backwards to help you in whatever way they can.

Throughout there were numerous speakers, all of which had their own angle. However, if there was one which stood out from the crowd, then it was 'Birds Can Save The World' by John Fitzpatrick. Straight away the title of the talk caught my eye. The underlying theme of his potent lecture was that birds change people; by understanding their populations, movements and requirements then we don't just understand them, we see the bigger picture – the whole ecosystem. If one thing in the chain is altered then the birds will be affected and, given how they're the easiest group of organisms to study, by studying and conserving birds we aren't just conserving them, but also the ecosystem in which they live, because everything relays on one another.

There's a saying in American Conservation that "all birds are like ducks". Following the extinction of Passenger Pigeon, the most abundant bird on the planet, the next species that was feared to be lost was Wood Duck, which today you would never have thought of as on the brink. The saying was derived from the conservation efforts applied to saving Wood Duck. It was thanks to these efforts that America's foremost act of legislation for conservation was introduced: the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The act doesn't just recognise that a species itself needs to be protected, but the environment it depends on is also just as important.

By the time the talks were over there was just one more thing before we could call it a day, a night in the museum tour with Irby Lovette. For the two hours we were given unrestricted access to the 58,000 specimens which the Lab held and naturally after a tour around the place, we headed to the birds section. You name it, they had it: Eskimo Curlew, White-winged Crossbill, Crab-plover, Wandering Albatross, Snowy Owl, Least Tern, Ivory-billed Woodpecker and even a shed load of gulls, including Ross's, Sabine's and Ivory!

We were afforded fantastic comparisons such as Ringed and Semipalmated Plovers, as well as Little and Least Terns, nominate 'European' Black and American Black Terns, plus the Royal Terns. There was tray of Northern Flickers which they'd gathered from a recent collection trip in the central flyaway as we walked in the room, including both Yellow-shafted (eastern) and Red-shafted (western) birds. During the last ice age, the ice sheet that covered central North America caused species pairs to form on the eastern and western coasts, in this case the two 'types' of Northern Flicker. Now the ice has gone, there's a 100-mile buffer zone running through the interior continent which is littered with hybrids. Fascinating stuff!

14 July

Once again, it was an early wake-up call for an dawn start at Montezuma. Starting at the east side of the reserve, the group were greeted with views of Sandhill Crane, Bald Eagle, Northern Rough-winged Swallow, Willow Flycatcher, Bobolink, Green-winged Teal, Turkey Vulture, American Wigeon and Northern Pintail before the site's first Louisiana Waterthrush shot over calling, probably my best find of the trip! The group was mostly half asleep so we were taken up the road to a little known place to hopefully get some improved views of Black Tern.

Chris was right, we were rewarded with insane views of Black Tern, the best views of any marsh tern I'd ever encountered both in the states and back in Europe; at times they were so close that not even the cameras could focus! In addition to this, the wetlands were alive: Killdeer, Solitary Sandpiper, Common Gallinule, Swamp Sparrow, American Coot, Double-crested Cormorant, Green Heron, Eastern Kingbird, Marsh Wren and Least Bittern. Here I learnt something which until this moment I'd never really thought about: once juvenile herons and raptors have fledged the nest in the south (such as in Florida or Texas), some will migrate northwards to cooler climates.

American Black Tern (Elliot Montieth).

Then we took a trip to Cayuga Lock and River Road as news broke of a 'Greater' Snow Goose. It was infact an injured bird that had been shot several months before by hunters and had survived with its entire summer spent on the lake. It provided close views (no doubt it'd get called "plastic" back home!), as did a Caspian Tern, several Ring-billed Gulls and a Western Osprey.

15 July

It was good to reflect on our final day on just how good the trip had been. Not only had we notched up 144 species (of which 107 were lifers for me), but we'd heard from inspirational professors, researchers and students.

My generation is a fortunate one: never before has there been so much more support for young ornithologists. The sheer quantity of events out there is simply outstanding, whether it's the scholarship to Cornell, the BTO, HOS or RSPB Bird Camp, having access to grants such as that offered by the BTO & British Birds to allow you to travel to a British bird observatory and learn the ropes of the trade or even to help fund a project. The list goes on. There are so many opportunities out there and if there is a young birder reading my report, don't be afraid to go out there and try something new. If you want help or guidance then the folk at both the BTO and Cornell will likely help in whatever way they can. All you need to do is ask.

Our final day in Ithaca birding was no different from the rest, with the first port of call being a small bog just off a country road. At first it seemed lifeless, but soon as the tape started playing … Virginia Rail and Sora on the list! Pine Warbler was also seen, but an attempt to see Acadian Flycatcher failed (though brief views of Barred Owl made up for it). Next up were Magnolia and Hooded Warblers, while Belted Kingfisher was another addition and we enjoyed the tail pattern of a Taiga Merlin. Afterwards we went to the best site in town for Fish Crow, which was nailed on call, before we returned to the lab and said our farewells.

Magnolia Warbler (Elliot Montieth).

The list of people to thank is endless. For starters there's everyone who I've already mentioned from the Lab above, and in particular to Jessie and Chris for housing me when my flight was cancelled. Then there's the other young birders who I met – it just wouldn't have been the same without the likes of Baxter, who I learnt so much off. Without the support of Zeiss, the event might not have even been possible, and then there's the people who made this happen: Corinne Bespolka and Keith Betton of the Cameron Bespolka Trust. Without them, I wouldn't have been there in the first place – and I have so much admiration for the work they do, so on behalf of all the young ornithologists they've helped on either side of the Atlantic, thank you!