In the first 20 months of the BTO's Cuckoo Tracking Project we have learned a huge amount about the migratory journeys of Cuckoos. With them, we have experienced summer deluges, Spanish drought, the hazards associated with migratory journeys and the hunt to keep up with seasonal flushes of insects in Africa. Migration for Cuckoos appears to be an even more risky business than we expected and, even with only two groups of Cuckoos to look at, it is obvious that there can be huge between-year differences in the challenges they face.

All five birds ringed in 2011 were still transmitting data in December of that year but, of the 14 males that left their breeding sites in 2012 only five were still transmitting in December, one being Chris, now providing a second year's worth of data. At least two of the losses this year (Roy and Mungo) are, we think, associated with tag failure rather than the death of the birds. Given that Cuckoo numbers in the UK are declining, one of the key aims of the project is to try to understand the circumstances that may be contributing to increased mortality. Knowing how and when we lose marked Cuckoos is as important as understanding their migratory journeys.

The Class of 2011

In the first year of the project we tracked five male Cuckoos, hoping that (in line with estimates of survival from ringing) two or three would complete the round trip to their mystery wintering locations in Africa. We were surprised and delighted when all five made it as far as Africa and astounded that they revealed new information about early departure dates and a new migration route through Spain and western Africa. You can read more about the class of 2011 here. The return journey was trickier, with Clement being lost soon after heading westwards from the Congo forests and Martin succumbing in Spain. Particularly poor weather may well have been to blame; we know that there were unseasonable hailstorms in the exact spot where we lost Martin, for instance. Kasper's tag is thought to have failed soon after he completed his northward desert crossing but Chris and Lyster were still sending signals when they returned to Norfolk — which was exciting news for everyone involved.

The Class of 2012

Given its success, we expanded the project in the summer of 2012 to include males from Scotland and Wales. We were keen to discover whether Scottish birds, whose numbers do not seem to be declining, might have different migratory strategies (which may just be the case — read on!) and to look for east–west differences between Norfolk and Wales. BB, Chance, Mungo, Roy and Wallace were tagged in Scotland, while David, Indy, Iolo and Lloyd began their journeys south from Wales. John and Reacher joined Chris and Lyster as our East Anglian representatives.

Most of the Class of 2012 failed to make it to the African wintering grounds — in complete contrast to the Class of 2011. Hopefully, as we analyse this year's data, and start to add data from future years, we will better understand the rules of the game of 'snakes and ladders' that Cuckoos face each autumn, winter and spring on their 10,000-mile round trips. The summer of 2012 was wet — very wet, with a real dearth of insects — and we were concerned that migratory birds may be in poor condition when it came time for departure. This was not the last of their problems, however, as we would see over the autumn period. We can only speculate as to what proportion of the losses was associated with conditions on the ground in southern Europe and how much was due to poor preparations in the UK.

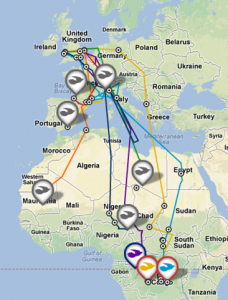

Fourteen Cuckoos were tracked at the start of the project.

Grey markers indicate that we are no longer receiving

transmissions from those tags. (BTO).

In 2011 migration was relatively straightforward, but in 2012 there were a number of cases where we saw birds return northwards, presumably because they could not find food. Lloyd sampled sites in northwestern and northeastern Italy as well as in southern and southwestern France before making it across the Mediterranean, while John gave up on Spain and returned to France. We guess that Indy's U-turn in the middle of the Mediterranean, as he flew back to northern Italy, must have been associated with running out of resources and going back to his last known feeding ground to refuel.

We were surprised when, in 2011, two of the tagged birds successfully used a previously unknown westerly route through Spain and western Africa. In 2012, no bird that took this option completed the journey. John died in France, Reacher died in the droughts of Granada (Spain) and Lyster did not manage to complete his journey across the Sahara. Chris, who was the only English Cuckoo to take the more easterly route, made it across the desert and south to his wintering area in Congo.

Route taken by four English Cuckoos in 2012. Grey markers indicate that we are no longer receiving

transmissions from those tags. (BTO).

It is early days and these are small samples but, looking at the routes taken by East Anglian, Scottish and Welsh birds, there do seem to be some interesting patterns. The only birds using the western route were tagged in England. Scottish and Welsh birds overflew the southern coast of the Mediterranean in a broad wave, from Tunisia to Egypt, with two birds (and possibly a third) using countries east of the Adriatic as stop-overs, while Cuckoos tagged in England have crossed from coastal Morocco east through to Libya across the two years. Perhaps the westerly route is good in some years and not in others? Of the five birds to reach the wintering grounds, the two birds from Wales are wintering further east than the remaining English and Scottish birds.

We had also hoped to include five females in 2012 but they proved very tricky to catch and the weather was not on our side. BTO scientists managed only to tag one female Cuckoo above the acceptable weight limit — Idemilli. Unfortunately, the weather in Wales was uniformly wet at the time that she needed to prepare for her migration. She is likely to have had a tough time finding enough food to fatten up, which may explain her presence in a Surrey garden, where she suffered injuries when attacked by other birds. She was found in a sorry state and the decision was taken not to leave the tag on.

We do hope we will be able to tag and track females in the future, but this depends on being able to catch them, and they do need to be a suitable weight. They also proved much trickier than the males to lure into the nets. They leave on migration later than males to make the most of the breeding opportunities. It's thought they store sperm and continue laying eggs in host species' nests after the males have left. Juveniles leave even later.

Looking forwards

There is a lot more to be done to understand Cuckoo migration fully: studying the same birds in different years (currently only Chris has been tracked in both years of the project), assessing the effects of weather conditions, gaining a bigger sample of birds from different regions to look at the routes taken, looking at whether host species has any effect on migration, the timings and routes taken by juveniles, as well as females, and much more. However, all of this work requires funding.

The two different routes taken by Chris to reach the same area within Congo where he would winter in both years. The dark red line shows transmission from his tag for the period spring 2011 to spring 2012, while the purple line is from spring 2012 to Jan 2013. (BTO).

If you would like to help support and develop the project, you could become a Cuckoo sponsor for as little as £10. You will receive email updates on the Cuckoos' progress and your name will be featured on your chosen Cuckoo's blog. If you have already donated, please consider further support for the class of 2013. We will reveal the newly recruited Cuckoos in late spring. Find out more about Cuckoo sponsorship here.